“That’s the thing about history, you know, history is capital. The reason why I think the distinctions are worth knowing about is while communal responses, political responses, like ACT UP are incredibly valuable and noteworthy, there’s also power in the individual voice. It was six gay men, who had no idea that they were surrounded by a community that was going to come into formation, who made this poster. And I think for an activist in 2050, after I’m gone, and you’re old, it would be helpful to know that a room full of people can seize the commons. You don’t need to fully organize a movement in order to utilize the commons.”

Avram Finkelstein is an artist, writer, and activist, and is one of the founding members of the Silence=Death Project, ACT UP, and Gran Fury. He is well-known for designing iconographic posters during the HIV/AIDS resistance movement of the 1980s. A self-proclaimed “red diaper baby,” Finkelstein’s work often uses the capitalist system and its codes against itself as activist strategy. His work can be found in the permanent collections at the MoMA, The Whitney, The Metropolitan Museum, The New Museum, The Smithsonian, The Brooklyn Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum, and The New York Public Library.

Sarah J Halford: Could you speak for a moment on your formative years? How you got involved in art and if that happened to intersect with you being a politically-conscious individual?

Avram Finkelstein: Yes, yes, and yes. They’re all connected for me and they always have been.

I’m a “red diaper baby.” Both of my folks were members of the American Communist Party – they actually met an an International Workers’ Order summer camp in rural Pennsylvania where my father’s mother was the cook. So, I come from a politically engaged family. We used to go on lefty retreats and they were members of the Utopian Artist Community in upstate New York. My grandmother used to come to peace marches with me, so I was sort of raised with this idea of the world, that I didn’t fully connect to as a gay man, until the AIDS crisis. But when I was a teenager I canvassed for the Student Mobilization Community Against the War on Vietnam, and I stuffed envelopes for the Poor People’s Campaign, and my brother gave me a baby Lenin pin when I entered middle school. So, I was kind of born with a poster in my hand, pretty much.

One of the closest friends of our family was a graphic designer and did work with the WPA. My dad and I used to go to museums every Sunday in New York, and spent a lot of time – when the Whitney reopened downtown they – their most recent show, “America’s Hard to See” – they had an entire room devoted to Social Realists, and I had sort of forgotten that my father and I had spent a tremendous amount of time at the Whitney when I was a kid, because of the Social Realists. So, it was very much my upbringing, I spent a lot of time at museums with my father and I came from a political background, so the two were always connected in my mind.

I was politically active anyway, but to be a kid in the ‘60s, it was such a political moment, the entire world was politicized at that moment, so I had a very romantic idea about the world and the ways in which activism could be articulated through art. I’m also Jewish and there’s a tremendous history of Jews and social movements, and artists who were Jewish who were doing work around social issues. So, I was kind of raised to be this way.

SJH: For your own artistry, what is your chosen medium?

AF: I consider myself to be an artist, you know, I write as well. My early influences as an artist were formed from the early 20th century. I was hugely influenced by the Dadaists, some constructivists, some modernists, but in the ‘60s I became very focused on the Situationist critiques, which of course were very instrumental in the May ‘68 strikes in France. Steve Rate, who had been at the May ‘68 strikes, came back with some posters, and that’s how I learned how to silkscreen – reproducing those posters.

SJH: Well, then let’s jump forward a bit to the 1980s. There’s been a lot written on that time, and the tension that brought about resistance groups such as ACT UP, Gran Fury, and the Silence=Death Project, but in your own words, I’d like to know how you would describe the political climate of that time, and what kind of feelings and thoughts were stirring up within you?

AF: Well, it was pretty nightmarish actually. To go from my teen years of being so politically active, and my early years in the ‘70s of pursuing my art career and thinking about how I wanted to be in the world as an artist – and it was a terrible moment politically in America – but I was absorbed in a whole other set of things.

In 1984 – it was before Rock Hudson was diagnosed, Reagan had never mentioned the word, it was a very private moment to be experiencing what I did. So, I formed a consciousness-raising group with three of my friends and I suggested that we each invite one other person that the other two didn’t know, and we met every week to talk about being gay in the age of AIDS. This was 1985. So, I was struggling to try to figure out how to be in the world, what to do. Of course, I thought I was going to die myself – there was no HIV test back then, so you just had to make assumptions about yourself. But we met every week, this collective, and every week we would start out talking about personal issues, but we would inevitably end up talking about political things. Someone would bring a press clipping – and it was pretty obvious early on that there was a political crisis brewing as well.

(Consciousness-Raising Anonymous Collective, circa 1985. Avram Finkelstein pictured at center)

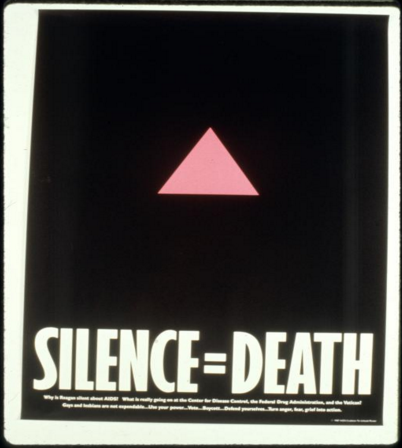

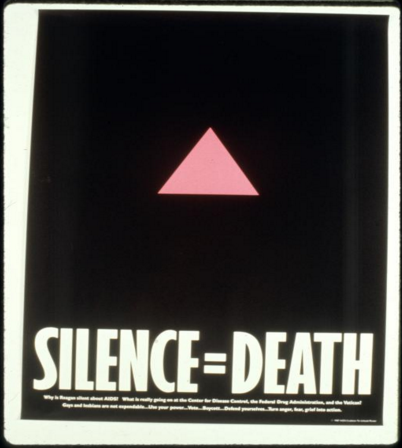

So, because I had that background of student activism and being raised on the left, and the experience with posters in particular as a part of social change, I suggested to the collective that we do a poster. And that’s how the Silence=Death poster came about. It was basically an idea I had. You know, we didn’t have smartphones in our pockets to connect to the world – the way that young people communicated was in the streets of New York through posters and advertising meetings or demonstrations. People used the streets so I thought, “Why can’t we do this now?”

SJH: So, this three-person collective, was that the Silence=Death Project or was that the beginning of Gran Fury?

AF: That was the Silence=Death Project. We each invited three other people, so there were six of us total. It was a men’s consciousness-raising group based on feminist consciousness-raising principals. We were unnamed; it was an anonymous collective.

We worked on the poster off-and-on for about 9 months. It wasn’t the sole purpose of our meetings, so it took us a long time. We spent a long time, but we finalized it and put it to bed at the end of 1986. I had this idea that it should be wheat pasted by professional wheat pasters alongside advertising posters.

The problem that I gave to the collective to solve, was that the poster needed to speak to two audiences simultaneously and imply two different things: for people outside of the gay community, I wanted it to appear as if we were completely organized politically around HIV/AIDS. It was pre-ACT UP, so I wanted it to seem as if we were completely organized, but also to create a space for the community to organize politically around this issue. And I had this idea that we would have professional wheat pasters do it, and because there was some expense involved, we decided to wait until spring when the weather was better and there were more people on the streets of New York. So we started wheat pasting it at the end of February, and ACT UP formed within two weeks.

So, the appearance is, in a compacted historiography, in the elevator pitch of activism, it seems as though Gran Fury, ACT UP, the Silence=Death Project all happened at the same time, but the sequence was: it was a six person collective that was anonymous – it was anonymous because this was going to be the first in a series of posters that would call for increasingly radical responses. In fact, I wanted to try to stage a riot during the elections. But, ACT UP came along in the interim, so we folded into ACT UP.

After ACT UP formed within weeks of the poster, Bill Olander, the curator of the New Museum, approached me to offer the windows of the New Museum to ACT UP in the summer of 1987. He’d seen the Silence=Death posters and was aware of ACT UP, and he contacted me through David Merriam (of the “Testing the Limits” video collective) to offer the windows of the New Museum, and I formed an open committee within ACT UP to do the installation at the New Museum, which led to the formation of Gran Fury in 1988.

The open committee within ACT UP had a sliding membership and there were up to 50 people who worked on that window. It was during the de-install of that window in November of 1987 that the people who had worked on the window decided that they wanted to continue to work together, and that constituted as Gran Fury. So, technically Gran Fury didn’t exist until 1988.

SJH: Interesting how that timeline gets conflated.

AF: It’s just, that’s the thing about history, you know, history is capital. The reason why I think the distinctions are worth knowing about is while communal responses, political responses, like ACT UP are incredibly valuable and noteworthy, there’s also power in the individual voice. It was six gay men, who had no idea that they were surrounded by a community that was going to come into formation, who made this poster. And I think for an activist in 2050, after I’m gone, and you’re old, it would be helpful to know that a room full of people can seize the commons. You don’t need to fully organize a movement in order to utilize the commons.

SJH: How did the other people get in contact with the six of you in order to form ACT UP, just weeks after the poster?

AF: Well, that isn’t exactly how it happened. Larry Kramer was the only person who was writing about the politics of AIDS in New York at that time, and I was paying attention to his writing. He was the most radical, political voice at the time. He was speaking at the community center, so I suggested to the collective that we meet there instead that night. We basically were there for the talk that Larry gave, which led to the formation of ACT UP. So, we were founding members of ACT UP because we were in the roomful of people who heard Larry’s talk.

We were there for this catalytic event, and within a few weeks after ACT UP formed, somebody asked if anybody knew anything about the Silence=Death poster, because we were still anonymous at that point. So, we came out, and that began the use of Silence=Death by ACT UP.

(Pictured: a photograph of the original Silence=Death poster circa 1986)

SJH: Going back to the logistics of the poster itself, can you talk about the process of coming up with what it looked like – the colors, the fonts, all of that?

AF: Yes, and again, the strategy was a bifurcated audience: the gay community, and people outside of the gay community. It needed to intone full authorization, so we sort of utilized the language of capitalism as a sleight-of-hand to create the illusion that we were more organized than we were. And as a consequence, the message was also tiered. We knew that New Yorkers used the streets but many people live in the outer boroughs who work in New York and use public transportation or drive cars, so I wanted it to be visible from a moving vehicle, but also function to create a sort of performative interaction on a more intimate encounter that was more targeted at the lesbian and gay community. The slogan “Silence=Death” is the big picture thing that raises questions about the poster that would entice you into a more intimate encounter with it.

We relied on the code of the pink triangle, which was used in concentration camps for gay men. So, it drew on gay codes, but we also changed the color of the triangle and the direction of the triangle, so we were sort of creating a new idea about the conversation, because we were a little squeamish about intoning the idea of victimhood. It was about empowerment, not about victimhood, so we didn’t want to directly relate it to the camps, but we wanted to draw upon those codes.

On the bottom of the poster were two lines of “situation text” that were meant specifically for the gay community. The text was about the pharmaceutical-industrial complex, religious leaders, government leaders – it proposed several ideas about boycotting and how lesbians and gay men should defend themselves. It was meant to be the set up to two more posters that would actually lead to a call to riot.

The reason that we chose that font – on the typography, the standard-sized printed poster at that time, it was only about 29 inches wide, so we needed something that could be read from a distance, which meant it had to be a super-condensed typeface. So, we chose “Gill Sans Serif” which was very on trend at the time. We wanted the poster to also draw upon fashion codes and music codes, and plug into other ideas on what communities were. It was meant to intone a “knowingness” which is why we were conscious to make it trendy. Again, the signal of capitalism is that you want to know about this thing or you will be out of it if you don’t. So, a lot of the graphic solutions were based upon trends.

SJH: You’re talking to people in a language that they can already understand.

AF: Yes. You’re drawing upon multiple languages, so the pink triangle was for the gay-male community, the color black was a fashion color and a music color – the original pink triangle was a pale pink but we made it fuschia because it felt more “MTV” – and we inverted the triangle as a disavowal to the direct connection to the camps.

The reason why we did an iconographic poster, as opposed to a poster that involved representation was – in fact, the first idea that we had for the poster was going to be about William F. Buckley Jr. who had called for the tattooing of HIV-positive individuals, and we were outraged by that, so it was going to be the subject of the first poster – but the more we thought about it, the more we realized, how do you depict a tattoo without a body? And if you have a body, what color is that body? What gender is that body? And realized that in order to really talk about the larger political issues that we knew were there, we would have to conquer the question of representation and didn’t want to exclude any of those audiences. We knew that people of communities of color were impacted, that women were impacted, and no one was talking about those things, but we intended to.

So, we decided very quickly through that exercise of the tattoo image that it had to be iconographic. And then we went through, okay, what are the recognizable icons for the gay community? And there were really only a handful of them. There was the laberice, which we loved, which came out of the lesbian separatist movement, but it was something that gay men wouldn’t necessarily . The rainbow flag was ugly, but it also had some hippie baggage and we felt like it didn’t have gravitas, and the lambda was also very class-based and we didn’t feel comfortable with it as an image. We didn’t actually like the pink triangle either, but we knew we had to choose something. For a while we were even thinking about designing a new image for the lesbian and gay community, but we realized that that would be whole separate endeavor and that could take years. So, we basically reinvented the one that we hated the least, and that’s how we ended up with the pink triangle.

SJH: So this was the first poster in a sequence of three. Did the other two come to be in the way that you had planned originally?

AF: No, they didn’t. But, you know, ACT UP came along so we didn’t need to . You know, I’m a notetaker so I have some notes and sketches of what what the second poster might have been. (Finkelstein holds up old sketches from that time) This was a rejected sketch for the poster that was a demonstration scene – that was when we were still thinking about a photographic depiction – and this was another idea that we had of the raising of the flag in Iwo Jima but having queer people do it. The lines of text here say “Second poster: gay riots are the only way! Gay riots in 1988, we are not expendable!”

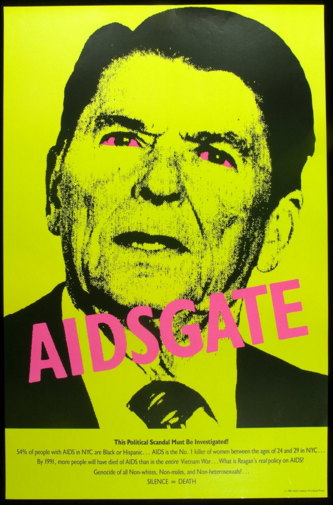

So that was where we were heading, we hadn’t gotten that far, and then ACT UP came along and we, instead, did the AIDSGATE poster as our second poster. And we did it because in June of that year was the first ACT UP demonstration in Washington D.C., it was the first demonstration at the first international AIDS conference, and it was the first national civil disobedience about HIV/AIDS. So, we felt like it was a very significant moment and we thought it was an opportunity to sort of expand on the issues of race and gender, and to also put Reagan right in the middle of the question of the holocaust, which the Silence=Death poster opened up that conversation. That poster also has lines of modifying text that were meant for the lesbian and gay community, and it talks about the number of people of color who were affected by HIV in New York, the impact of it on women in New York – I don’t have the statistics of the off the top of my head, but it was shocking – it was the number one killer of women in New York.

(Pictured: ACT UP’s second poster circa 1988)

SJH: Which points to the fact that HIV/AIDS is a hetero problem as well.

AF: That’s right. It sets it up by giving these statistics, and then it says, “So what is Reagan’s real policy on AIDS? Genocide of all non-male, non-white, non-heterosexuals. Silence=Death.” So, that was what that second poster was about.

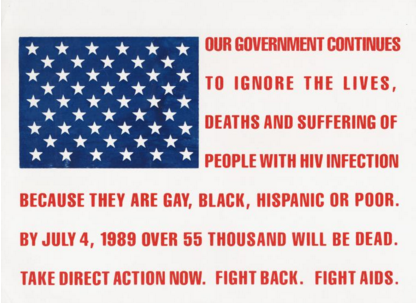

SJH: And the third one?

AF: The third one ended up being a “vote” poster that almost no one saw, because we thought, “Okay, well here is this radical communal response through ACT UP – we don’t need to now call for riots. Maybe we should try to figure out how to get people to vote this single issue.” So, we made a “vote” poster with “Silence=Death” superimposed over the American Flag. Not many people saw it. It wasn’t particularly good. It was just another strategic thought that we had since ACT UP was heading in the radical direction, we thought “OK, let’s do something else during the election.”

(Pictured: ACT UP’s third poster, circa 1989)

SJH: You mentioned that there were two audiences that you wanted to reach: the gay community, and everyone else. So, what was it that you were trying to say separately to each of those communities and to both of those communities together?

AF: Well, Silence=Death is the “together” thing. But there are many things that are happening in that phrase. It’s very densely packed, this poster, because it’s meant to imply a ton of things that weren’t being described at that time. We’re talking about 1986, when we made this poster, and before ACT UP came along, and way before Reagan even mentioned the word. So, it pivots all over the place. But, Silence=Death also relies on public spaces as a dialogue, and uses the interrogative in a Socratic way. So, the slogan is declarative, the slogan is accusatory, but the two lines of text – there were a few declarations in it, but they were posted as questions. “What is really going on?” Why was Reagan silent about AIDS? What’s really going on in the FDA and the CDC and the Vatican? So it’s asking questions that are taking the accusation – we’re saying Silence=Death and we’re basically saying that you’re culpable wherever you stand on this issue, you are a participant in this. So, Silence=Death is for all audiences.

Then, the very first line of the text underneath it, we pivot away and talk about Reagan. The very first line is, “Why is Reagan silent about AIDS?” So, what we’re doing is, we’re connecting him for the lesbian and gay audience who’s going to stand there and read it, or for the person who’s not necessarily from the affected communities but cares enough to want to know what this means, we’re then pivoting away from the audience’s culpability to Reagan. We’re down-shifting and asking why he’s silent about AIDS, so we’re making him responsible for it. We then ask a few more questions. We knew that people weren’t talking about the pharmaceutical-industrial complex – that was something that came out of AIDS activism. My mother was a research scientist. She did cancer research, and when I was a kid I asked her if there would ever be a cure for cancer, and she said, “Oh 100 times over, but there won’t be, it’s too big of a business.” So, I was raised with the awareness that capital is involved in, you know, all of the feminist critiques of health care and research, but not every gay man, and not every person in the gay community thought that way. So, we wanted to set up that set of conversations, and the question marks about the pharmaceutical-industrial complex were things we were going to elaborate on later. It was a throw-down.

SJH: So, when people saw the “Silence=Death” poster – if you could have pinpointed one thing that you wanted them to do upon seeing it, what would that have been?

AF: Well, that was the second line of text – so the first line asks these provocative questions, or leading questions, and again, it was meant to be a first in the series and we knew that it was just the “grabber” it was the beginning of a campaign.

One of the things that we discussed at length as a collective was that it was an apolitical moment. You asked earlier what the political environment was like, it was completely reactionary, and terrifyingly so, and the things that Reagan did, you know, there were things that people weren’t even paying attention to at the time that we’re still paying the price for, like with his de-regulation wand, he defunded – there was something like twenty agencies that collected public information about political records, records of political events. He defunded them to the extent that it went from 20 some odd to 2 or 3. So, in that one gesture of deregulation, he basically wrote a whole range of things out of history. And there were things like that happening everywhere. It was bad.

So, it was an apolitical moment and a reactionary moment where people were thinking about the public’s fear and thinking about social issues, it was this sort of “Republican Happy Talk of Ronald Reagan.” So we purposefully knew that the poster couldn’t be text-heavy, it couldn’t be a manifesto, even though it needed to be, because no one would read it. It wasn’t the 60s. We couldn’t explain all these things in depth. And I’m very didactic and very flat-footed and that would’ve been my choice, but as a collective we realized we couldn’t.

So, the second line of text suggests actions. The first line sets it up like, “What’s going on here? OK, Silence=Death, people are dying, then here’s a couple of things that I don’t really know about – I wonder what that means? I should know more about that.” So it raises some questions and involves the audience. It’s performative in a Socratic Way.

Then, the second line of text suggests a series of things that one might do. And they’re purposefully vague. So, lesbians and gay men should use their power – that was a phrase we used, because we wanted to intone an empowerment without suggesting what the action might be yet, because we were going to keep moving in a more radical direction and this was the beginning of the conversation of what the solution might be. The three we mentioned were “vote” – because we knew that there were a lot of people who were not radical in the lesbian and gay community. Everyone we knew was, but there were many people who weren’t. “Boycott” was another thing that the gay community had participated in successfully, with the boycott of Minute Maid orange juice over the Anita Bryant thing or the Coors boycott, or the boycott over the movie Cruising. So, vote, boycott, and then the third was “defend yourself.” So, that was the radical suggestion, but we didn’t say what that meant yet. And then, “Turn anger, fear, grief into action.” So that was the final thing that we’re saying, we’re saying, OK, direct action is where we’re heading with this. So, we went from very moderate responses, boycott and vote, to more radical ones, defend yourself and action.

SJH: So, really the purpose of this first installment in what was to be a three-part series was to get the conversation started.

AF: It was a conversation starter. I’m trying to get people to, in a very condensed period of time, to go on the record in a public space about an issue that’s important, to convince people that you don’t need to say everything that there is to know in one poster. Storytelling – that’s what public spaces are for in capitalism, they’re for storytelling. Stories are told one sentence at a time, or one word at a time. So, all we’re going to do today is come up with the first sentence. And that’s exactly what Silence=Death was doing. It was a conversation starter.

SJH: So how did you know if the conversation was started based on that poster? Obviously ACT UP came out of it…

AF: ACT UP came out of it, but of course, you know, that’s a complicated social dynamic at work there. Within the historiography of activism, Silence=Death is the ACT UP logo. You now know that’s not what happened.

SJH: Right.

AF: It was actually a consciousness-raising project that had a completely different objective than what a logo does. It wasn’t a branding idea – well, it was – but we were branding a radical response. If the collective had a client, it was radical action, it was resistance. That’s not something that one can really brand, but when you’re talking about social movements you could say that ACT UP was branded by Silence=Death. We know that that’s not actually true.

I feel like the question of the meaning of this poster is completely mediated by every single aspect of how you’ve heard about it, how the people who responded to it heard about it, what they thought that AIDS meant at that time, and because we purposefully used a sleight-of-hand that used capitalist devices, there were many people who were stakeholders at that moment, radical people in ACT UP who you see in news footage fighting with cops who also thought it was a logo and came to it because it was “cool.” The sleight-of-hand that we used, we paid a price for that. The price was: capitalism gets to use it as a representation of resistance – it’s a cardboard cutout of resistance – and it actually doesn’t talk about the more radical parts of it because what it does is it gets to claim this resistance movement as a product of a way that capitalism works. It’s a productivity fetish for “free expression.”

SJH: So, the fact that it actually fed into the capitalist system and became part of the conversation that people understand because they are privy to capitalist rhetoric all the time – is that sort of an indicator, or perhaps the metrics that you used to gauge “success” in this particular project?

AF: I think it’s a double-edged sword. I’m a Marxist but I’m also a Machiavellian. My father and I had a huge fight – the last fight we ever had was about ACT UP, and it wasn’t that he wasn’t proud of what we were doing or didn’t agree with it, but he actually thought there was going to be a revolution in America, and because there wasn’t, he thought that there was no way that we could do what we were setting out to do. And I said, “Look, I have two choices: I either do something, or I don’t do anything and I know what happens – people continue to die.” And you have to realize people were literally dying in hospital corridors and being thrown out of their apartments and dying on the street. It was…bad. It’s impossible to understand how bad it was. And I said to him, “Maybe what I do will work and maybe it won’t, and if it doesn’t work, I’ll try something else.” That’s how I thought about it, and that’s how I continue to think about it.

The thing about the media landscape is, it’s always on. You step into it and you can also step out of it. Media’s interest, media landscape, how we talk about things as a culture, how we think about things changes all the time. So, it isn’t about being definitive, it’s not about ending AIDS, it’s about this constant ongoing struggle of “OK, if I do this, they’re going to do that, and then what do I need to do to move it over here…”

So, the metrics, I knew that we were going to pay a price for some of the things that we did, but they advanced way beyond my expectations some of the other things that I didn’t think were going to happen. And I think, I don’t know if I agree with this assessment, but there’s some treatment activists who feel like, for instance, the question of gay marriage would not have existed if it hadn’t been for spousal rights in hospital rooms. And so the AIDS activist movement, in a way, bore the marriage rights question and I don’t personally know whether I consider that to be a huge achievement for civil rights of lesbian and gay people, but it has moved it a step in a direction. It would not be my strategy – not my strategic thinking at all.

SJH: When you put out a piece – regardless of it it was the Silence=Death poster, or anything from Gran Fury or ACT UP – is it possible to draw the line from putting it out into the world to the realization that your work did something? Are you able to connect your art to tangible change?

AF: I don’t see it that way. So, we designed Silence=Death, but it’s actually the activist community who responded to it that “created it.”

Think expansively about it, OK, so it’s 1986. It’s deregulation on steroids. The cable news business, media conglomerate, were in the process of being deregulated. So, it was now possible for people to have 24 hour news cycles, that was a brand new idea. So, here you have a disease that no one knew anything about. There was no test for HIV in 1987, you couldn’t even tell if you had it. There were markers for it, but people thought that you could catch it through mosquito bites because it was based on the exchange of bodily fluids. So, there was a tremendous scare about it, there was a 24 hour news cycle, and there was an audience hungering to know more about it. So, a journalist didn’t have to struggle to pitch a story to their editor about AIDS in 1987. They had 24 hours of news to fill.

So it was a perfect storm of effects – it wasn’t just us and this poster and this little activist community. And again, in the historiography of AIDS activism it makes it seem monolithic, but ACT UP New York was a couple of hundred of people, it wasn’t thousands of people, it wasn’t millions of people. And everyone pretty much knew each other, it was a pretty small movement, actually. So, you can’t divorce the social context from the ways in which we have come to think about this moment.

SJH: It’s an interesting thing that this piece of art, this poster, translated into an activist group. If we’re talking about art in the context of community organizing, do you ever entertain the idea of a ratio of art and organizing? As in, you need “x” amount of community organizing and “x” amount of artistry in order to create some kind of tangible change?

AF: The truth is that there are two things going on: it’s late-stage capital, and all of the trappings of it. It’s also an image culture, which is attached to culture, but not directly, because images have existed long before capitalism did. The ways in which we conceptualize things have very much to do with the way that they appear to us. And this is where it gets really messy: social spaces, public spaces, aren’t just determined by focus groups and advertising language and efficacious messaging – that’s how we refer to it when we’re trying to understand the ways to best use it. But the truth of the matter is, the psychodynamics of public spaces have more to do with Jung than they do with Marshall McLuhan or Foucault.

To us, we’re in a bubble. We think about this stuff – most people don’t. Images and image culture are like backgrounds in a cartoon – they wash over us. We don’t even know they’re there half the time. We don’t know why we’re responding to certain things and not to other ones. So, whole industries are built around describing how to think about these things, and we’re both a part of those industries in a way, this is what we do, this is our world. But for the rest of the world, they don’t really know why they’re responding. And the thing with HIV/AIDS in particular – we’re talking about mortality and sex. Those are two really primal questions. All of our literature is connected to them, religion, spirituality – it’s so primal.

As a propagandist that is what I’m looking to do – is to tap into the most primal part of the question that you’ve asked. To try to figure out ways to strike the right chords to move the direction into the way that I want it to move in.

SJH: But after the conversation has begun, and it’s moving in the direction that you want it to, then what?

AF: Well, a lot of people think in terms of political movements as a pendulum swing – they move to the left and move to the right – and I don’t see it that way at all. I actually think that politics is a spiral and it’s always going forward. So you’re always encountering something you haven’t encountered before. It’s the nature of social spaces and of history for it to constantly be changing. So, we all know that America’s dirty secret is race. It always has been – it probably always will be. And yes, there are things that are equivalent to, and probably worse than lynching, but I doubt you’ll see people lynched in the public square anymore in America. Maybe I’m wrong, but I doubt it.

SJH: We hope not.

AF: Yeah, I mean, you know, there are millions of ways to be lynched – I’m aware of that. I’m being really reductive just for the sake of trying to explain my point. So, in a way, the spiral of racism is that we’re now in another place with it. It’s not that we’re back and forth, left and right, it’s actually moving in a direction which hopefully is forward. I’m an optimist, so I believe that it does move forward. So, I think that’s the tricky part of trying to quantify something like this.

Hear me in the back of your head every time you’re thinking on this as the Jew who says, “Anything that’s given can be taken away, it’s a spiral, it’s always changing.” I’m a lifer – this is war, it’s war with capitalism, and it never goes away. It never stops, unfortunately.

So, the quantifiable question is a question that is the professionalization of the realities of the actual psychodynamics of public spaces. If you want to become a marketing person, you would need to know the answer to the question that you asked. But if you’re a political activist, you don’t really need to know what combination of effects is going to work. Because it’s only going to work for a minute.

SJH: So, would you say to creative activists that it’s a waste of time to try to figure out how something worked or didn’t work?

AF: No, I think it’s a project in flux. I wouldn’t say it’s a waste of time, I would say that the objective is to train one’s eye critically and to look for the meaning in every move that you make, and the meaning of every response. Gran Fury, we used to go around and photograph our posters so we could study the homophobic graffiti, so we could learn about the audience and study them.

Nothing is a waste of time – it’s all meaningful. The question is: the idea of resolution is an idea that’s based in a fantasy about capital, and that’s a fantasy that applies to – a fraction of the 1% of people who are privileged have the that luxury of capital, which one could refer to as “resolved.” The rest of us are on a constantly changing set of hierarchies about privilege. The nature of privilege is that it’s a one-way mirror: you don’t even know it’s there, unless you’re on the wrong side of it. So, it’s a constant moving target.

What we’re talking about doing, effecting change through creative endeavors is a very vast project that’s always in flux. The mistake isn’t thinking of it as quantifiable – the best way to approach it is to think of the looseness of it and to become adept at a looser set of responses.

SJH: But certainly there must be moments when you put a piece out there when you think, “AH, yes!” That something about that feels like a “win.” Have you ever felt like that?

AF: Oh yeah, many many times.

SJH: Can you give an example of when you felt that way?

AF: Well, I did a series of Flash Collectives, and I actually think that the most amazing thing about the way that we conceptualize about public spaces and public engagement is that I believe that any group of people, when you give them permission to or give them the opportunity to, will have tremendously subtle, intelligent, and radical things to say about the world around them. I think we mistake that. The idea that people don’t care, I think is bullshit. capitalism is contingent, it’s predicated on us being balkanized and to be engaged. But I don’t believe it to be in human nature.

So, I’ve done 15 Flash Collectives, and I loved every single one of them and was awestruck by every single one of them. But there were three or four of them that I think were so spectacular, so vast, and so complex. One was a lenticular postcard that I did with the New York Public Library Flash Collective. It’s basically a “wiggle picture” and it’s about viral undetectability.

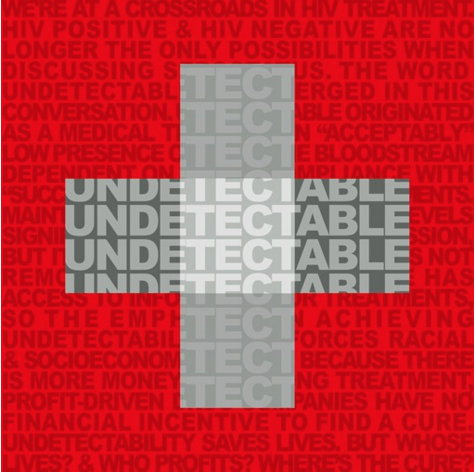

(Pictured: The Flash Collective’s lenticular postcard on viral undetectability)

In the past, you were either HIV positive or HIV negative, but because of pharmaceutical interventions that so mediate the body chemistry, it’s possible to be in neutral states of HIV, which they refer to as “undetectable.” It’s a very vast and complex set of physiological things that contribute to undetectability, but people talk about it as if it’s a discreet thing. It also has political meanings form a class, race, and gender perspective, if for no other reason than that access to the medications or the insurance to be able to afford the medications that would mediate your viral detectability. So the idea of it as a social panacea, as a curative, as a functional cure, is completely based in all of these political, class, and race realities. And that’s what this piece is about.

So, the thing that disappears and appears is that, while it says “undetectable” in both directions, it’s a positive sign and a negative sign mixed, and when it goes away there’s a two or three sentence text that talks about what the meanings of it are. And it says, “We’re at a crossroads of HIV treatment. HIV positive and HIV negative are no longer the only possibilities when discussing zero-status. The word ‘undetectable’ has emerged in this conversation. ‘Undetectable’ originated as a medical term for an acceptably low presence of HIV in the bloodstream dependent on strict compliance with successful antiretroviral treatments” (meaning that they sometimes work and sometimes don’t) “Maintaining undetectable viral levels significantly reduces HIV transmission, but it’s not a cure for AIDS and does not remove stigma.”

So here, we’re pivoting. We’re saying, ‘OK, it is what it is, it’s good for these things, it’s contingent on participation, on compliance, on being able to afford it, all that stuff, but even if you have it and you’re undetectable, it does nothing to remove stigma.

“Because there’s more money in life-long treatment, profit-driven drug companies have no financial incentive to find a cure. Undetectability saves lives, but whose lives? Who profits? And where’s the cure?”

So, I consider this to be completely brilliant. I’m like awestruck that a room of 20 strangers could explain such a complex thing. Now, it’s not vernacular language, it isn’t. But it’s translated into 5 different languages, including two Chinese dialects. We made a 30-inch poster of this that was mounted in four library branches in the outer boroughs of Manhattan, and it links to a Tumblr page that gives all of the details about those specific things. So, it’s super packed. I don’t know – it’s not going to end the AIDS crisis or explain this complex thing in ways that everyone can understand, but I consider it to be a brilliant gesture at unravelling one of the hardest things to explain to people.

So, this is an example of something that I consider to be wildly successful. I’m so in love with this. And really – that’s the point of resistance: to communicate the possibility of participating in a different way.

SJH: If you were to have to pinpoint a few things that are absolutely necessary for an artistic activist to put out there, what do you think a piece or a movement absolutely must have?

AF: I think that vernaculars are essential. First of all, I think that art that isn’t about communication is about class. So, if you’re an activist who’s making art and what you’re trying to do or say is not clear, you’re no better than being in a Gagosian Gallery. It’s not activism if it’s not understandable. So, clarity is essential to having an audience understand it.

Think about museums for instance. The reason why none of work that I do was ever designed for museums – though some of it has reached museums – is because what does it mean to be in a museum? Where people who are well educated don’t even know what they’re looking at? Like, super smart people who could be brilliant research scientists have no idea what they’re looking at when they’re looking at a de Kooning painting. So, what does it mean to be in an environment that’s so densely coded that people on the top of access to wealth and culture and education can’t even understand it?

So, the most important thing is clarity. I think that vernaculars are used in advertising for a very good reason. People understand them. So, I feel like vernacular language – the failing of this piece that I love (the postcard) is that it’s complicated. It talks about zero-status. No one knows what that means, but there’s no other way to describe it in brief. But by and large, the simpler, the better.

The third thing is knowing your audience – now, of course I’ve given you 5 separate things that have multiple audiences. How do you signal to multiple sets of audiences at one time? You use codes. And if you look critically at every piece of advertising, every journalistic report, everything is just packed with codes. So I think understanding codes is a key thing as well.

Audience, brevity, clarity codes.

SJH: So, Avram, I’ll end with a slightly cliche question: if you could have a conversation with your younger self, would there be anything that you wish you could’ve known about back then that you know now?

AF: Well, I think the thing that you’ve hit on, and that we’re talked about, is the price one pays for appropriating the language of authority. And I knew it was happening at the time, I didn’t think we had any choice, but I felt like there could be hell to pay to people thinking that Silence=Death was a logo, and in some ways I think we have paid the price for it.

There’s a tremendous conversation at the moment about what an ethical construction of AIDS historiography might look like. And I think that a lot of the tensions in that conversation are in some way rooted in the idea that viral suppression is rooted in political strategy. Which, at the time, there was no choice – people were dying so we had to literally fight for drugs. What does it mean when that becomes your political strategy? So, I wish we had been able to maintain more of a radical posture than we did, but we were way more radical than I, or than my father, imagined that we could be.

I guess, the fifth thing, if I already named four things that an artistic activist needs to know – the other thing I would add to that is: I am not squeamish about my own fallibility. I am very happy to concede that I have done things that I would do differently now, but I don’t think that it was an error to have done them, I just think that now I would do something else. So, I might be much less quick to suggest to someone that they might brand a movement, but I’m also aware that branding is part of an image-culture.

In some regard, all of this is branding; each bit of resistance is a gesture toward encapsulating an idea in a reductive way. And I think that’s just the price of admission. So, I’m grateful to be in the quandary of having to worry about the 24/7 news cycle. I knew that we were painting ourselves into a corner in some ways, but what choice was there, right? And I wish that public spaces were more radical than they are, but I am also aware if I had called for a riot that it might not have functioned the same way that ACT UP did. It might not have succeeded.

So, I have an idea about radical resistance that is somewhat romantic. What was the Marx quote? Something about – capitalism is so ingenious because it’s the only system that has constructed itself in such a way that it can never be dismantled. And I think I’m over mourning the fact that it can’t be dismantled. I don’t agree with my father on that one. I feel like you have to fight anyway. Because, what’s the alternative?

You must be logged in to post a comment.