It’s not that we have a vision necessarily, but we try to poke holes in the scenery – a scenery which is built up by the politicians, by the media. They are playing theatre, too, with our lives and with our destinies. We are making a counter-theatre to go against theirs. So, by poking holes in the scenery, we are trying to get a look at the truth, to see what’s under the surface. It’s about building bridges in the real reality.

André Leipold is an artist and Privy Counselor at the Center for Political Beauty (Zentrum Für Politische Schönheit) in Berlin, Germany. As self-described “aggressive humanists,” members of Political Beauty utilize shock-inducing tactics in order to draw attention to political wrong-doings. Past works include “The Dead Are Coming” – a nod to Sophocles’s “Antigone.” As a part of this work, the organization exhumed the bodies of several refugees who died in their attempt to reach safety and gave them a proper burial in Germany. In their most recent artwork, “Eating Refugees,” the Center for Political Beauty asked refugees to volunteer to be eaten by Libyan tigers in order to draw a connection between the Colosseum games of Ancient Rome and the current realities that refugees are facing: freedom or death (more on these works throughout this interview). As a result of these artistic choices, their work has been characterized as extremely controversial, pushing the boundaries of what is socially, and perhaps morally, acceptable in order to inspire others to create change.

In addition to his work at Political Beauty, Leipold is a singer, music producer, and performer.

Sarah J Halford: As an organization, what is the Center for Political Beauty? And what do you do there?

André Leipold: We are a combination of humanists and artists, and we try to create facts inside of reality. We work with the tools from the theatre but with tools from other art forms too, and we try to work as an interface between reality and wishing. It’s about breaking metaphysical and physical borders.

When we first started to think about making this kind of political artivism, or activism…actually, that’s not our word for it. We always said that we are making theatre. We are a theatre in a more ancient way; we started by breaking borders of categories inside the university, and over the years it became more literal, by breaking physical borders.

I am the so-called “Privy Councilor.” We try to find fictional words for our task fields, because they’re not really comparable. Inside a theatre, I would be something between an author and a dramaturg, but those definitions don’t really fit our stuff. So, it depends on where we are inside the production schedule. In the beginning, I’m conceptualizing with Phillip , I’m framing, I try to find out which words should be dominant inside of the action, I try to bring some poetry inside of an action where we are working with and against politicians. For some people, it sounds like a political movement, but in some ways we try to create the imagination of a political movement, and in that, I try to bring some poetry in it, too. But, under the assumption of, or imagination of, a political movement.

SJH: I noticed that all of Political Beauty’s works are officially categorized as “artworks” rather than campaigns or actions. Is there a reason for that?

AL: The reason is, more or less, not to fall into a category. The best space of opportunity to do that is within the theatre. Theatre, by the ancient definition is already an interface. It is already a spot where you can find out where artivisim or activism is. So, the artistic space is the best location for us so that we don’t run into that dangerous field of categories. Theatre is the most abstract, but in a way fitting for the work we do.

SJH: Within that abstraction there seem to be sprinkles of a lot of things – art, traditional activism, legislative work —

AL: We are humanists and we are artists. Usually an artist likes to show his picture in a museum and says that he doesn’t want to explain the work so much. We say, “No, we are connected with political visions.” We have to explain because there’s a concrete aim that we are looking for, and we’re taking our artistic competence to do so.

So, it’s not really “free” art then. The freedom of art is what we are diminishing for ourselves, because we are giving it a label and a concrete aim. So, for years now, it’s been about refugee politics, but not only about the refugees, it’s about borders, it’s about European politics. Connecting art with political vision is what you would maybe call “artivism,” but for me it’s more about bringing all of your own artistic competence in a pool and accepting that it’s not free. It has an aim. A goal.

SJH: Activism typically has aims and goals, as well. Are you sacrificing the ability to make “free” art for the sake of adding an activist element to the work?

AL: Yes, but…I don’t really like the words “activism” or “artivism” so much, because that concept is already inside of the old definition of theatre. So, for me, I don’t need this new category.

SJH: Tell me – what’s special about the ancient definition of theatre, then?

AL: The old definition of Greek theatre is to build a platform for the old society, which was always more than some actor’s play. It was always a space where society can find itself and talk with itself, and look at itself in the mirror. Building mirrors is what we do, too.

Above: a short video from the artwork “Eating Refugees” by the Center for Political Beauty.

TL;DW: The Center for Political Beauty demanded that the German government change an antiquated law that would prevent refugees from flying from Turkey to Germany. If the law was not overturned, they said, it would be equivalent to the German government sentencing the refugees to an almost certain death, by drowning or by other dangerous circumstances on their way to safety. To illustrate the draconian nature of this law – drawing a connection to the government of ancient Rome, which played with the lives of their citizens in the Colosseum’s gladiator games – Political Beauty set up an arena with four tigers and asked refugees to volunteer to be eaten by them.

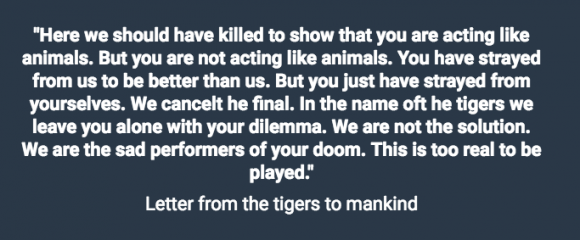

Editor’s Note: In the end, no refugees were eaten, though some did volunteer. The artwork ended with a “letter” from the tigers, translated from German, seen below:

SJH: I’m curious about the term “assault team,” that you use to describe yourselves, where you say that you practice “aggressive humanism.” Can you tell me a little bit about why you’ve chosen “assault team” and why aggression is important in your work?

AL: Traditional humanistic work is very polite, usually, and what we are saying is that we need other ways to communicate humanism within Germany and the European society. In our latest work with the tigers , the animal rights groups reacted very strongly to it, which is good – they should, and they have to – but we are looking at empowering the humanistic side, too. Aggressive humanism means throwing out politeness for the sake of the work. When you look at organizations like Amnesty International or others, there is a ritualism and very weak visions, very weak pictures too, and it’s not because they have no money – they have a lot of money – but there are too many people inside of the pre-production. There are too many voices.

And so, aggressive also means being sharp, being not so much tied to an organization that also has a say in the matter. As a musician, when I’m writing a song, I don’t write the song with 50 people, I write it with 2 or maybe 3 people, and even with the addition of those voices, it’s already beginning to dull. To not have to explain so much in a time of pre-production, where it’s very important to bring your thoughts completely on the table and not thinking so much about morals or manners.

SJH: Tell me, then, about one of your favorite artworks that you thought was successful.

AL: For me, it was the “First Fall of the European Wall“. it was a very magical moment for me. On this Saturday afternoon, we took out the white crosses and sent them on a vacation to the woods in Melilla . It was a very strong feeling for me. It was magical because there was a moment when I felt like we were truly an interface between a strong vision and reality. We built up something like a moral pressure chamber, which opened up a blind spot. To feel that, for me, it was very magical stuff. The words that we were creating were then used by the media and politicians. Some months later, we discovered that newspapers were very much inspired by it. To feel that you are someone who delivers inspiration to the right hands…it’s a very good feeling.

“First Fall of the European Wall” by the Center for Political Beauty.

Political Beauty took the white crosses, which commemorated the victims of the Berlin Wall, out of the government quarters just before the anniversary of the fall. Above, the empty frames of the crosses can be seen, with three paper-made replacements.The organization transferred some of the crosses to a fence on the European border and gave others to refugees at a camp in Melilla, Morocco in order to illustrate for the government – and preemptively commemorate for the world – that they would be “the next refugees to die at Europe’s external wall.”

SJH: So, it created a magical feeling within you – did you see any indications that it was going well outside of yourself? Did you notice the people respond in a certain way?

AL: I didn’t notice it outside of myself, so much. For me, it was magical to see that it was possible to have some kind of influence in spheres where you typically don’t have a connection with as an artist or citizen. To see that there were some politicians and journalists who really understood what we wanted to make, who said to us later that it was very inspiring for them, this was magical. What I mean by magic is that it’s possible to communicate with people in another form, in another way than by words. Through pictures and imaginations, to experience that they are not only seeing the hidden pictures in an artwork but also that they understand them, too. And I don’t mean only seeing the picture of the stolen crosses, but seeing and understanding the imagination that we wanted to create. They started to work on this imagination too, which was also magical because we didn’t plan it. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

SJH: So the feeling is really important.

AL: For me, yes. To feel what is going on. What is going on is not what you are reading in the newspaper, it’s not what the politicians tell you, it’s not what the theatre tells you, really what is going on – you just have to feel it, I guess. This is a strong motivation for me: to find a way of communication under the stream of data and irrelevant polls, tweets, views, and to find that there are hopes, wishes, dreams that we all share already. In that sphere of collective unconscious, that is where I want to build bridges. It’s more important for me than some other stuff, because the result you see months later is that part of the inspiration that we created has settled somewhere, and is beginning to be a fact. This is very strong. So, there’s a fear of media and of politics, and a fear of responsibility; this is where I want to bring pressure and inspiration. First, you need pressure to shake it. Then, you need inspiration to hold it.

SJH: Do all of your artworks turn out that way? First, the pressure, the shock value, and then the inspiration to make change?

AL: We always try to make it like a mobile washing machine, so that even if you are connected with the issue and you’re following the politics of it, that you don’t know anymore what’s right or what’s wrong. It depends on yourself and your own deeper feeling to decide on what’s right or what’s wrong now.

SJH: Have you ever seen that “deeper feeling” work within the public or political parties to the point that it created tangible change?

AL: The Vice Chief Editor of Die Zeit, which is a big weekly newspaper here, told us that after the action at the European border the entire editorial staff had discussions for weeks, not about the action, but about the subject of this action.

It’s not that we have a vision necessarily, but we try to poke holes in the scenery – a scenery which is built up by the politicians, by the media. They are playing theatre, too, with our lives and with our destinies. We are making a counter-theatre to go against theirs. So, by poking holes in the scenery, we are trying to get a look at the truth, to see what’s under the surface. It’s about building bridges in the real reality.

SJH: So, it’s as if you create the controversy, and you make some people angry, perhaps, but it serves to direct people’s attention to the issue at hand. Is that where the “bridge” is built?

AL: Yes. It’s stressing people. And when you are under stress, or under pressure, you don’t think so much about about the words that you’re saying, but it creates a good moment for truth.

SJH: What kind of audiences are you making these artworks for?

AL: We address different publics, and have different moods for different publics; the audience is very diverse, I would say. There are activists who imagine us to be working more in the movement, and then there are artists, people from the theatre, who understand our work in a more artistic way. Then, there’s the media, the universities, and they are all interpreting us in different ways, with different words. And making stress means bringing all of those different views together in one pot, mixing it, and seeing what comes out.

SJH: You’re okay with some people interpreting Political Beauty as an activist group and for others to see you as a group of artists?

AL: Well, we are all of these things and more.

SJH: Interesting. So then, if the organization itself is left up to interpretation, then how do you determine the “real reality” that you’re trying to create?

AL: All I can say is that it depends on the situation, what the moment calls for. Real reality is not my truth, it is not your truth, it is a combination of all of the truths.

From “Memorial: To the Unknown Immigrants”, part of the artwork “The Dead are Coming”, by the Center for Political Beauty.

A description of the moment above from Political Beauty: “Right after the idea for the cemetery had been announced, these determined members of our civil society set out to build it. They tore down the fence guarding the Parliament’s front lawn and dug hundreds of graves in an act of spontaneity.”

SJH: Some organizations, especially in the political world, tend to turn away from people who are fully entrenched in their “truth” in order to reach those who are more on the fence, but it seems like Political Beauty actually wants the people who have their minds made up. They stir the pot.

AL: Yes, they stir the pot. And we want them to be empowered – not only for the normal citizen but for the politician. They have opinions but they don’t really feel empowered to talk about their visions for the future. They are very much inside a framing network that they have to be empowered to break out of that, too. So, I think it’s empowerment for individuals, for individual units.

SJH: So, what is your relationship to the media? Do you invite them to your performances or do they come on their own?

AL: We invite the media, but I don’t think it’s so important for the Center for Political Beauty to get to know them. For me, it’s important to know them for the sake of my other work. We are all artists for ourselves, too, and for that it’s much more important for the individual experience than for the Center because they come to what we do anyway.

“Rescue Platforms on the Mediterranean” from the artwork “The Bridge” by the Center for Political Beauty.

Description from Political Beauty: “Every year, thousands of refugees drown in the killing fields at Europe’s external borders. According to Jean Ziegler, the death toll is at 36,000- more casualties per year than the total number of people who died at the Iron Curtain during the entire duration of the Cold War. In order to fight this silent dying efficiently, we will install 1,000 rescue platforms: 1,000 navigation lights as an international commitment to humanity and a monumental symbol of the 21st century. So far, every civilisation has left a mark of magnanimity and generosity on history.”

Editor’s note: the plan for the installation of the 1,000 platforms never came to fruition.

SJH: Can you tell me about a time when Political Beauty put out a piece where you felt like it just didn’t work?

AL: Sure. It happens more in the small actions than in the big actions. We had a small action in Austria last year called “The Bridge”. We wanted to be very positive and sunny, giving people inspiration, but it wasn’t very complex. It was just the imagination of this bridge between Europe and Austria, and the imagination of platforms in the sea to help prevent refugees from drowning. But it wasn’t about pressure, it was just more about – we’ve got so much money and why not spend this money and give people an imagination for this now. What we experienced was that people called it “nice” and it had some good results, but the media wasn’t really interested in it because it wasn’t hard enough. It wasn’t smart enough. There were no corpses, there was no stealing of crosses, there was nothing that they could write about. So we thought, okay, we have to find aggressive elements because otherwise they won’t hear us. They won’t look at us. We need that attention in order to lead them toward inspiration.

SJH: So, without that pressure and that aggression, nothing can be done?

AL: Nothing’s happening. No.

SJH: Those platforms in the middle of the sea, are they currently being used by refugees who may be forced to swim?

AL: There’s just one, but I don’t know if it’s being used. Maybe some rich guy’s wife uses this platform to lay in the sun, who knows?

SJH: Some organizations that use aggressive tactics to get media and audience attention have trouble with over-saturation. People come to expect shocking things from them, so after a while it becomes less interesting to them. How do you, at the Center for Political Beauty, prevent that from happening?

AL: We talk about it, of course. Yeah, this is a problem, sure. People know already what we do, they know what to expect from us, so it’s very hard to go a step further. Being even more aggressive or more drastic isn’t always the right way. So our answer to it is to work more, to strategize more, using the resources that we have now.

SJH: Earlier, you said that working with other organizations in the pre-production stage can dull the work, but what about the tasks surrounding the artwork? Do you collaborate with other organizations to do things like distributing petitions or working directly with politicians – the more administrative tasks that take place at a different time than the performance?

AL: No, it’s not something that we organize. Maybe our work inspires others to do these kinds of tasks.

SJH: Do you keep track of whether or not that happens?

AL: Not at this time, not formally, no.

From “The Dead are Coming” by the Center for Political Beauty

SJH: And what about working directly with refugees? Have you ever collaborated with them on your works or sat down with them to ask what immediate problems they have that they’d like to address?

AL: We spoke to them as we developed , to ask the families permission to exhume their loved ones’ bodies and give them a proper burial here in Germany. But we have not asked them to help us develop the work. They have to deal with serious, life-threatening situations on a daily basis; they have no time to worry about art and we don’t ask them to do so.

SJH: But they’re aware of Political Beauty’s work?

AL: Sure.

SJH: Have you spoken to any of them who feel like the work is effective in helping them?

AL: So, they often know of our work, but really, they are dealing with too much in their daily reality. They allow us to do it, but they don’t think it will help them, necessarily.

SJH: Political Beauty gets a lot of criticism from both sides of the political spectrum because of the measures that you go to. The right says that the work is immoral, that it goes too far, so it’s disgraceful – the left says that the work uses refugees as props for the sake of art, so it’s disgraceful. But Political Beauty has seemed to embrace that criticism; you even have direct quotes on your website from your critics. Do you ever feel ethically questionable about the work?

AL: We do embrace the critics. It all serves to build the pressure, to empower people to start talking. Rarely does society enjoy confrontation, but the stress from confrontation is what can inspire people to act.