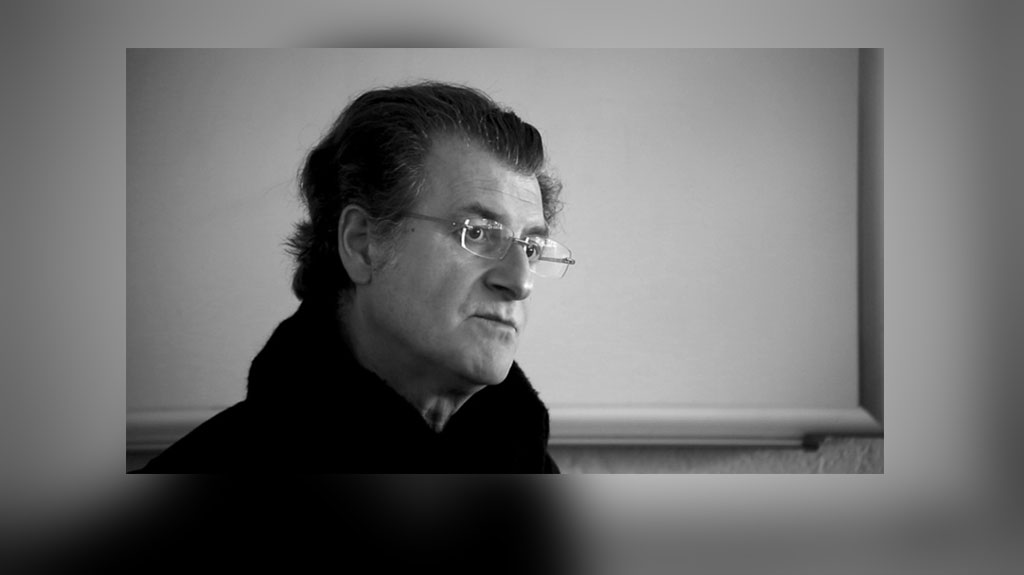

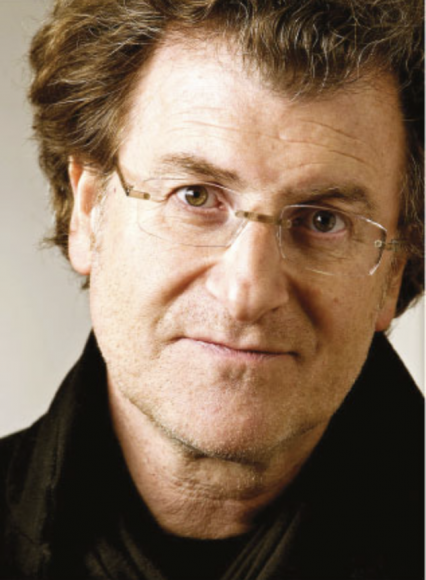

Alfredo Jaar is an artist, architect, and filmmaker who lives and works in New York City. He was born in Santiago de Chile. Jaar has realized more than sixty public interventions around the world and more than fifty monographic publications have been published about his work. He became a Guggenheim Fellow in 1985 and a MacArthur fellow in 2000.

Steve & Steve: So, how do you approach your art?

Alfredo Jaar: I believe that art is communication, and I never forget that communication doesn’t mean just to send a message, communication means to receive an answer. If there is no answer, there is no communication. So the entire process is a process of dialogue. but still, you need to have a certain minimum knowledge of the place before actually intervening. And so it’s very, very important to engage the community in a dialogue. And who are you to come in from the outside and do something in there? You have to gain their respect, their knowledge, and their generosity. You have to gain it. And you gain it with showing your commitment. So I think that it’s very important to do that to guarantee the success of the work also.

S&S: You mentioned success, how do you measure success in your own work?

AJ: I always wanted to be an artist and my father thought it was a very bad idea, so I went into architecture as a kind of compromise. Yeah. So I still consider myself an architect making art. And I look at a space not as a physical space only as most artists do, but I look at it as a social space, as a cultural space, as a political space, I measure the success of my work according to how I have accomplished the program. And the thing is of course that each project has a different program, which is specific to that project, and so there are hundreds of ways to measure the success of each work, of the work, since there are different programs and different objectives.

S&S: Most people know your work from the Rwanda Project, can you talk a little bit about what got you started on that topic?

AJ: Right. In the case of the Rwanda Project, I had been shocked by the indifference, the criminal indifference of the world community. As you know, this genocide happened in less than a hundred days, a million people were killed. And I could not believe the apathy. my rage started growing and growing, and it reached a point where I said, okay, I’m going, I have to go. And I went as a witness, as a privileged witness. I interviewed people, I photographed the situation. I was there as an observer. I collaborated with certain NGOs that I admired pretty much like Médecins Sans Frontières, Doctors Without Borders, among them, which is one of my favorites, and I went to the UN meetings. I was there like any other photojournalist, and there were very few. So I wanted to inform. And of course, I wanted to inform with poetry, with art, it wasn’t just information like journalistic information. Journalism had failed to inform us. So I was not going to replace journalism. But I wanted to inform and I wanted to in a way recuperate some of the humanity we had lost by letting this happen without reacting. And so on a more personal level, I wanted to go to express my solidarity with the people there. I wanted to suggest, you’re not alone, there are a few people that care. I created different works. All failures. I did 25 works in six years. And so many in such a long period of time because I couldn’t stop. I just couldn’t stop. And each one had a different program, it failed and I moved onto the next one, it failed and I moved onto the next one. Of course, at the end, I learned a few things and I affected a few people. But the effect is quite minimal.

S&S: Why do you say that you didn’t effect anyone?

AJ: Everyone skipped the genocide, they went for the refugee images, that’s what was interesting to them. 800,000 people have died already, but that’s when they ask that question. They make even jokes. A full page joke. “Grace with death,” “Can they be saved?” All the wrong questions, four months too late. So this is what the press was doing but much too late. And no one was reacting, so I felt I could not use the same strategies, I could not show these images that I had, the most horrific images that I’d ever taken in my life because they wouldn’t make any difference.

S&S: How can you say that about your own photography?

AJ: Who cares? I’m very pessimistic. Who really cares? I do this, people can’t believe, they think I’ve faked the covers, and they ask themselves, where the hell was I at that moment? How it is possible that this happened? And who cares? Who actually does something about this? I mean, it’s frustrating, we do these fantastic things, and I really loved it, but then they dismiss it with a little thing one or two days later and that was it.

S&S: How about the people in your audience? Not just the mass media.

AJ: I don’t know. I really, I really don’t know what people think. The thing I know is that most people couldn’t care less. And I think we are still pretty much a racist country, I think the entire world is racist, each society in its own way, and the fact that these were black people, that they were poor people, that there was no strategic interest of any kind, there were no resources that we were interested in, we just let this happen.

S&S: So then, why didn’t you give up if you thought nobody cared?

AJ: Right, right. I ask myself that question all the time. And I don’t know why the hell I’m still doing this stuff. Because deeply inside I believe that somewhat, somehow a little change occurs in someone in the audience, not the audience, someone is touched, and I

can feel it. Most of them they come to me, sometimes they come in tears and they thank me and they say, you know, thank you. And those are the people that make me keep going. Because I can feel the minor differences that I can make in a few people out there. And thanks to them, those heroic individuals that acknowledge that I’ve made a little difference, that come to tell me, and they give me energy and the strength and the will to continue. If not, I would just commit suicide. And actually after Rwanda I wanted to commit suicide. And that’s what most journalists actually did. Because you feel ashamed of being a human being. You ask yourself, how is it possible that we allowed this to happen?

S&S: How did you move on from there? What was the next project you did, after realizing the mass media was too indifferent to change?

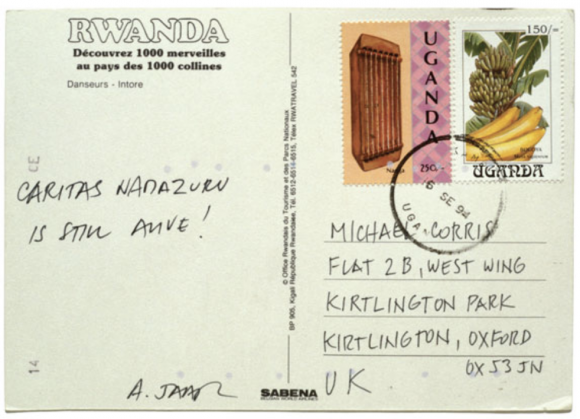

AJ: So, I had found this destroyed post office in Kigali, and there was a box with postcards. And I decided to start sending them out to friends. So I called this Signs of Life. And on the back of the postcard, I just said, put the names of people I was meeting in Rwanda that were people that were alive. So I wanted to send Signs of Life instead of signs of death. So I would simply say – blank – is still alive. So I have the stories of all these people I was meeting, I was just sending their names across the ocean saying, hey, – blank- is still alive. Caritas is 85 years old, she walked 300 kilometers from Rwanda into Goma, Zaire, the largest refugee camp in the world, and so I met her, we had a conversation, I photographed her and so on, and so she is still alive. And I sent signs of her to a friend of mine in the UK.

S&S: That sounds incredible. Do you consider that a failure?

AJ: Because it’s too late. I mean, what difference does it make? I mean… People were hearing only about death in Rwanda, and I was sending, you know, little cracks in the system, saying, okay, no, there is also life: here, here. Let’s support them, let’s help the victims, blah, blah, blah. But really, what can we accomplish with this? What can we really do? I mean, as an artist, you get success and critical success, and books and writings and exhibitions and blah, blah, blah, but in terms of real life and affecting the lives of these people, what do we really do? So some of these projects I’ve raised money, and those are successful in that practical sense. Others are more successful in a more conceptual sense or critical sense. Like to engage people in a critical dialogue, which I think is very important. That’s what we do as intellectuals, we offer models of thinking the world. And this is a way of thinking a conflict and a tragedy. So I was offered 60 of these light boxes around the city.

S&S: What city is this?

AJ: It’s Malmö in Sweden. And so it’s an anti-design poster, basically the word Rwanda in the most common font, which is Futura Bold, like Helvetica Bold, and as big as I could and as many times as I could. And so it was a cry. Rwanda, Rwanda, Rwanda. No names, no addresses, no phone numbers, nothing. I didn’t even have a hope that with a phone number or a place to help people would react. So I just wanted to send that cry. And because this was a non-profit organization, they gave me some light boxes that were located in places where nobody cared. They have very little visibility so they were cheap, so that’s why they were free. So, but I liked that because they echo the silence and the solitude of the Rwandan people. So these cries were happening in these spaces that were completely invisible.

S&S: Now, ideally, we have these people walking by, what would you want them to do, to think?

AJ: Well, here, I’m hoping that this word registers in their brain. And somewhat, somehow when they get home, or even walking in their shopping and so on, they think, what is this? What is Rwanda? Why Rwanda, Rwanda, Rwanda? And I hope that, and I have no idea what happened, if it stayed there, and if it made a little difference. So sometimes we try to accomplish too much. So here it’s really like the minimal strategy: let’s see if we can insert this word, which is a concept, a story, a history, into their conscious or even unconsciousness, and let’s see what happens.

S&S: I mean, do you think that it worked? How can you say that you tried to accomplish too much?

AJ: This one, I didn’t go, they had no fund to bring me, so I just sent the project, so I couldn’t measure it myself. But the press reacted, we made the front pages of all newspapers, so it was an interesting turn because they had ignored the thing and now suddenly they have this image and so in a way, subversively, it had a certain effect. But again, really, what effect did it make? I’m not sure.

S&S: So, if I am understanding correctly, making the front headlines doesn’t count as success to you because it was still too late? Hmm, what are other projects you have worked on that had an unintended effect?

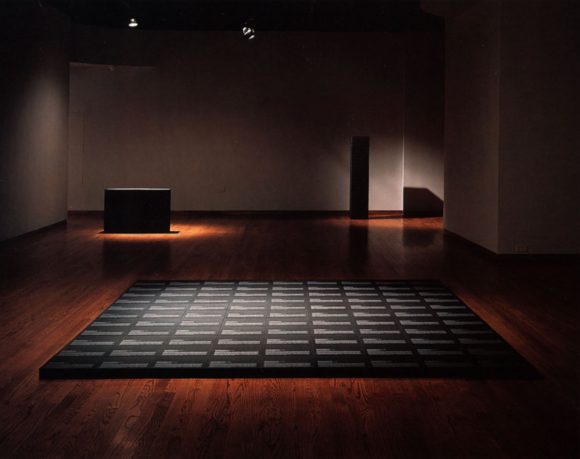

AJ: Absolutely. Then the first major installation is this one: it’s called Real Pictures. And here I was offered a convent in Spain. And what I did, I created monuments as a memorial for the people of Rwanda. And so the way I did it, I selected 550 images of the genocide and because I felt that to show these images would not make any difference, they have been seen and nobody reacted. If you think about it, if we still had some kind of humanity left in us, you are shown images of that horror, and you see them, you actually see them, what do you do? You go out in the street! You march! You stand in front of your senators, the UN, and you say stop this, do something! But nobody did anything. So I found that these images have lost their capacity to affect us. So that’s why we have to use different strategies. So this is another strategy. So what did I do? I encased them in black boxes. These black boxes are archival boxes for photographs. So they are safe inside. And they are sealed, and inside each box there is a single photograph, and on top of this box we have silk-screened a text describing the image inside. And I’ve used this box as a module, like a brick, and created this very simple monument. Stones, columns, walls, and they are in the dark, with very little light, in silence, it’s a space of mourning. So I used a reverse strategy. What this piece says is listen. We showed you these images, you didn’t react. Perhaps now that I don’t show them to you, you will see them better. I mean, totally utopian, absurd strategy, but I had to try something different. So this was installed in different places, so these are the monuments. So I’m inviting people to come in the darkness and to approach each monument and to look at them and to read. I was hoping that just the reading of what happened would create an image, and that image would be more powerful than the ones we saw because we are creating themselves, ourselves. So these were spaces of silence, with a lot of empty space. I was not afraid of the emptiness. And every box had an image, even though you could not access them, but it wasn’t important, for me it was important that each one contained almost like a spiritual proposition, to suggest that we can feel their presence there even if cannot see them.

S&S: So, is it perhaps better if we cannot see them?

AJ: Yes. So let me show you an example of a text. “Ntarama church, Nyamata, Rwanda, Monday, August 29, 1994. This photograph shows Benjamin Musisi, 50, crouched low in the doorway of the church amongst scattered bodies spilling out into the daylight. 400 Tutsi men, women, and children who had come here seeking refuge were slaughtered during the Sunday mass. Benjamin looks directly into the camera, as if recording what the camera saw. He asked to be photographed amongst the dead. He wanted to prove to his friends in Kampala, Uganda that the atrocities were real and that he had seen the aftermath.” That’s all. So, it was a memorial for the people of Rwanda, a space to suggest these are tombs of these images that we refuse to see, something died there. But it’s really a memorial for us, for this humanity that we have lost. And Rwanda is one of the best demonstrations of that lost humanity. And so normally when we show that work, we have what I call a resource room where we have a lot of press clippings and magazines and newspapers about the Rwanda issue and what the press had done on TV and so on. And some material from NGOs, non-governmental organizations, so people could perhaps help.

S&S: Do you think any people did help?

AJ: I don’t know. I don’t think so. Very few.

S&S: So, even though you could not measure the effects, you would call this a failure?

AJ: Well, critically that piece has created an enormous amount of literature. There have been books and writings and magazines. And so it has really affected the theory and practice about photography and the way we cover tragedies. So critically it had an impressive impact. I’m not sure that in the real world, what I call the real world, we really made a difference. That’s really my problem. That we can have a, you know, I think we can affect the world of culture and we can affect intellectuals, we can affect the next generations, that we can do. And I teach and it’s an important part of my practice. That, I can assure you, we can affect culture, but we still are waiting for that moment when culture as an activity, as an entity, as an important aspect of our life, can really affect the rest of life. Real life.

S&S: Ok. But you’re still an artist dealing with political issues. Why do you insist on doing the work that you do, even if you feel it doesn’t have any tangible effects?

AJ: Okay, in my case because I don’t know how else I could do it. What I do, I create models of thinking, models of thinking the world. And hopefully these models of thinking is, if other people and enough people apply them, confronting certain situations, the world will change. I really believe that. But for the moment, these models of thinking are marginalized, are marginal. And they are just intellectual exercises. But somewhere, somehow, if they get used by more people and by culture at large, then we will present really a model to the world in order to react in front of certain situations, and actually react and act and make a difference. So here uncertain about the effect of the piece, I created a space with the resource room where I offered index cards and pens to people to actually give us their opinions. This was just a week after the show started. And we had extraordinary reactions. And people expressing their rage—not to my work, but to the situation of course. And so that was good. And we offered a space and a way for people to vent their rage, and of course people feel completely powerless. They feel frustrated because there is nothing they can do. They ignored us. The media ignored us, the governments ignored us, the police ignored us. And did we make a difference? They couldn’t care less.

S&S: How can you be so hard on yourself? You seem to have so much doubt. Why do you continue doing what you do, if you don’t think it’s working?

AJ: Well, that’s the question I bring every morning when I come to this studio. And do not have an answer. And if I’ve done 200 projects in my life, each project is an answer, a different answer, to that same question. They all fail and that’s why I keep doing it.

S&S: You said you keep working in these sort of cultural areas because that’s that’s what you’re best at?

AJ: I divide my work in three main areas. Only one third of my practice is this, which is the world that takes place in museums and galleries and foundations—what we call the art world. For me it’s a world that is too small, too insular, in a way, and it is almost incestuous. I’ve spent another third of my practice doing what I call public interventions—where I confront myself to real life situations in communities removed from the art world where I try to resolve problems in a creative way and engage communities in a dialogue. Finally the third final part of my practice is teaching. I direct seminars and workshops around the world, and I share and I experience with new generations. And I learn enormously also from them. And so I feel complete as a professional and as a human being only by doing these three things at the same time.

S&S: In the eyes of those who are interested in socially engaged art your work is considered a success, both aesthetically and politically are considered a success, So why are you so pessimistic and skeptical?

AJ: Well I’m very skeptical, I’m a very depressing character, believe me. But I still do it because I, as I said, some people, very generous, have told me the impact that I have caused in their works or in their lives or in their… And that has helped me to continue. I have very high expectations. I really want to change the world, I want to change things, I want to make this huge impact, and want to… And it never really happens. Perhaps if I had lower expectations, I would say, oh I am very successful.

S&S: What piece of work has, even minimally, created an impact on your or others?

AJ: So here, this also has become a very important piece critically for me and for this discussion about how do we represent events. So I tell the story of what happened in Rwanda. One Sunday morning at a church in Ntarama, 400 Tutsi men, women, and children were assaulted by Hutu death squad. Gutete Emerita, 30 years old, was assisting mass with her daughter and her husband and so on when they were killed. Yes, she was attending mass with her daughter, her husband, and two sons. And so when the death squad came in, they assaulted the church, and they killed most people, and so she witnessed how her husband and two sons were killed with machetes in front of her eyes. Somehow, she managed to escape with her daughter and she, they hid in a swamp for three weeks.

S&S: Did you meet her?

AJ: In a swamp. And they came out at night only in search of food. And so I was visiting the area, visiting this place which is, I cannot describe it, and that’s when I discovered her. She had come out at night to, she was visibly disturbed. So we took her to the hospital and we helped her a little. But I tell her story here, and so Gutete has returned to the church in the woods because she has nowhere else to go. When she speaks about her lost family, she gestures to corpses on the ground, rotting under the African sun. And so I remember her eyes, the eyes of Gutete Emerita. So that’s the end of the text. Then I come in the scene, and I say, I remember her eyes, the eyes of Gutete Emerita. Which becomes the spectator reading this. And then so we have reached this point here, and we move into the next space. And we are confronted with a huge light table, which, you know, lights, that’s, photographers use to work. This measures 12 by 18 feet. On top of which we find a million slides. It’s really quite a spectacle. And so when we approach it, we slowly discovered that there are slides, we cannot see them from a distance, and we realize that there are loops all around the table inviting us to actually take a slide and look at the image closely. And that’s the moment I’ve been articulating, expecting, when the spectator finds himself two inches away, one inch away from the image, and that’s what they see. The eyes of Gutete Emerita. And they realize that it’s the same image repeated a million times.

S&S: This is a huge project. How do you go about constructing this story and installation?

AJ: In the first part, I tell the story, I inform, I say this is what happened and this is the story of that woman. So you reduce this strategy, which is one million, which are numbers, into one person, one life, one story, one name, one daughter, etc, etc. So you personalize it; you lower the scale from this big scale to one person. So that allows for people to identify with it. If you don’t do that, you’re lost. If you talk about, oh, 50,000 people died yesterday, it’s just a number. So it’s important to make it real by giving it a name, changing the scale. But this is the information part, and then when you move into the next room, it’s the spectacular part. And so you have to create a balance between information and spectacle. And only by doing this, in my view, you will not dismiss that image. It will make sense because you understand this image. If you do not understand it, it’s just an image and you can dismiss it. So something extraordinary has happened with this work.

S&S: How did the audience interaction with the slides? And with the project?

AJ: I’ve shown it a dozen times, and every time between 5,000 and 10,000 slides disappear. So the first time it happened, the museum guards called me, and they said, Mr. Jaar, please come. And they showed me the monitors, and we looked. And we saw people, we observed people how they would take one slide. And this was not part of the piece, it wasn’t designed like this. But what I observed was that they body movement, the body language of the people taking the slide was not communicating to me, hey, I’m stealing a slide. No. It was communicating something else. I said to let it happen. Don’t encourage it, don’t suggest you have to take one, but if the guards see this happening, they should look the other way. So we came up with a system with insurance where we count the slides at the beginning of the show and then at the end, the insurance pays us back and we put them back in. So we always start with a million. And so this means that today more than 150,000 people around the world has an image of Gutete in their homes. And I like that.

S&S: Why were they picking up the image?

AJ: I want to believe that they wanted to keep a momento mori of this situation, of this moment. They wanted to express their solidarity and that’s the way they were doing it. I want to believe that. Only once someone came to me and said, please sign the slide. I said, put it back there please. And so I’ve met a lot of people around the world that tell me, I have a slide of Gutete. And they remember her name, which is not an easy name to remember. Now: is that a success? You can say yes, but of what? Right? So that’s the Rwanda Project.

S&S: Wow. That is such a beautiful project and outcome! So what, if anything, constitutes reasonable success for you?

AJ: Yeah, the goal here was for me to create that perfect balance, which is for me a critical component of every single work of art we do, a balance between information, what we can maybe call didacticism, informative aspect of the work. If it’s too much information it falls into the didactic, propagandistic thing, and it’s really not interesting to me. But if it is too beautiful, if it is too spectacular, if the construction is too blah, blah, blah, then it becomes something else. I wasn’t expecting them to actually take it physically, but that was a demonstration for me that yes, they care about her enough to want a copy of it.

S&S: So what was the goal? Was it to stop a future genocide or find support for the people in Rwanda, or what??

AJ: Well that’s part of the big lessons that the piece is offering. By informing about this of course we are hoping that this will be not repeated. But this is just a cliché that I don’t even mention it anymore. Because everybody says, yeah, we have to know, histories are not repeated, and just look at history.

S&S: We repeat it over and over. How do you balance commercial success versus artistic success?

AJ: These institutions in general, all these non-government organizations. They give us a miserable image of the world, and it’s always about victimhood. And there is this fatigue because they don’t know how to do this. They have done it the wrong way. And so, and also when I do something like this I’m scared to death that someone will copy this idea for PepsiCola. So you have to be very careful. You have to try to keep that balance where you, you’re very effective, very sharp, voom, and you get out. Because if this becomes like a trend and everyone starts using this gift thing, it’s hell. So that balance is very difficult to strike.

S&S: It is a thin line for sure. What is a project that you think straddles this boundary well?

AJ: It has just opened in Santiago de Chile. This is a Museum of Memory and Human Rights, created by the government to tell the story of what happened during the Pinochet years, during the 17 years of Pinochet. I’m not gonna create a little object on the bottom of the plaza. So instead of competing with this building, I’m gonna go deep inside. So I created a hole in the ground. So this is my work here, facing this and facing the entrance. So it’s called Museum of Memory and Human Rights, and here we tell the story of what happened in the Pinochet years.

S&S: Could you describe the piece?

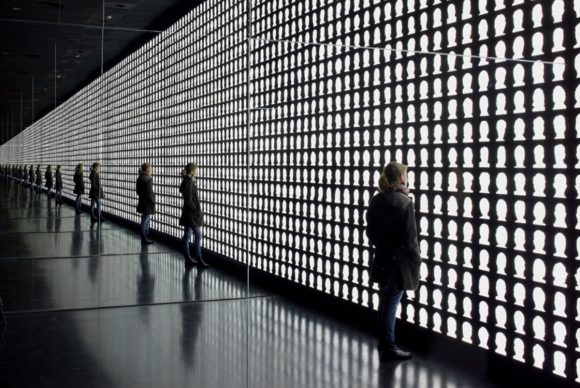

AJ: You walk down 33 steps or six meters and you reach a first five meters by five meters by five meters space, which is covered by these beams, so you are a little more in the dark, not exposed to the sunlight. The piece is called the Geometry of Conscience. It’s all concrete and glass. And the first space is completely, it’s a perfect five by five by five cubic space, all concrete, all dark, lights indirect from the two walls, so just a little light for you to see. And a second, a central door that will take you to the main space where the work is happening. On the left there is a little podium, which has the electronics of the piece, and here a guide from the museum will welcome you and say, welcome to the Geometry of Conscience, please turn off your phone, I will introduce you to the final space, and please remain silent for three minutes, the door will close automatically behind you and will automatically open after three minutes, if you panic, there’s a panic button for you to get out. So she’s there to organize people, we don’t want more than ten people at a time inside. And so people enter the space and the door close behind you automatically. And when you are inside, you are in absolute darkness for 60 seconds, for 60 seconds you are in the dark, the door is closed, you are in silence, and little by little you start seeing something in the back wall. Very little. You might realize that some silhouettes are there, but you don’t really see them. And then suddenly—after 60 seconds of darkness the lights start and they will go from zero percent to 100 percent in 90 seconds. So you will discover that there are silhouettes in the back and they’re illuminated from behind and they start glowing, and little by little, and they will reach an intensity that will blind you.

S&S: They blind you because of the lights! What are the silhouettes of?

AJ: These silhouettes are made of two types of faces: half of them are faces of the desaparecidos, of the missing people during the Pinochet regime, that they were killed and tortured by Pinochet, and the other half are people that are still alive in Chile today, these are not victims, they are living Chileans. So I wanted to have both of them, the dead and the living together. But we never see the faces, we only see this. And so as you start being blinded by the intensity of the light coming up, you realize that they two side walls are mirrored, meaning that this image is projected to infinity on both sides. And so then you understand that it’s really not about the people who died, but all of us. So there are 17 million Chileans living today. So what I, my objective here was not to marginalize the victims like most memorials do, I wanted to integrate them in a collective narrative for the entire nation. And I wanted to illuminate the living with the living coming from both the living and the dead. But the most important thing: I didn’t want to do this operation that memorials do that we put them, the victims, in these crypts and we marginalize them. No. They are part of us, we are together. We all lost something. And so after 90 seconds where we reached that blinding light, then voom, it goes down abruptly to zero. And you are again in the dark for 30 seconds. But those 30 seconds are very different from the first 60.

S&S: And you have those images literally seared into your brain.

AJ: Exactly. And so you see them even though it’s gone. So it’s about memory, experience, blah, blah. And after that, the door opens automatically behind you and then you just leave. So this is a public intervention, but it’s a permanent piece.

S&S: I mean, just looking at it here, I’m moved. And I didn’t even have the sensual experience of it. Are you looking at it as a failure because of the backlash it received?

AJ: No, here I’m still waiting to hear more reactions. I’m curious to see what happens. They said, the right will say, these leftists, they’re always exaggerating, look at these millions of faces, we only killed 4,000 people. So they’re gonna take it as if it’s just an exaggeration of victims.. And the left is gonna say, why is my father next to this guy who is alive? What is his personal life doing next to my father? My father died for the cause. What did this person do? And the living ones are anonymous that I shot in the streets of Santiago. And I’ve said, well, I don’t care, I think it’s important to integrate them in this collective narrative. And I went ahead for it. And so far, the reactions have been very, very good. Even the rightwing politicians have written about other things, and they quote me, saying we all lost something. So it’s quite impressive. So so far, I’m very, very pleased.

S&S: That’s really great. It’s good to be pleased…for once.

Extra:

S&S: That one was a permanent installation, but you work mostly in temporary installations. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

AJ: So why I do with these public projects, and I’ve done more than 60 in the last 30 years, is I work really as an architect, and I search for what I call the essence of the place. I try to understand the place by researching, by talking to people, by going back and forth, by reading their press, looking at their news, reading their poets, talking to people of all kinds, going back and forth, doing research from here, from the internet—until I accumulate a certain amount of critical mass. And there you can take risks. You are experimenting, you use the city as a lab and you try things out. It works, great, it doesn’t, doesn’t matter, you just move on. And when I feel I’ve arrived at the essence of the place, then I start formulating ideas, I confront my audience with it—it’s always part of a dialogue, I do not impose anything, I tell them, this is what I have discovered, am I in the right direction? Is this correct? So it’s a back and forth dialogue with the community, and we reach a consensus and then I act.