“I think there is something affirming of our humanity in culture – in the community building side of things. A connective tissue, quilting all of us together and creating meaning as you strive for these outcomes. That is different from operational politics – when you’re just trying to do turn out or get numbers or turn people out to a rally.”

–Andrew Boyd

A pioneer of viral activism, Andrew Boyd was one of the driving forces behind Billionaires for Bush and the Million Billionaire March. He founded, and for several years directed, the arts and action program at United for a Fair Economy, and currently presents and performs around the country. His writing has appeared in the Nation, the Village Voice, and several anthologies on recent social movements. Andrew is also the author of The Activist Cookbook, a source book on creative direct action, and is the co-editor of Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution, as well as several books of political humor published by W. W. Norton. He is an alumni of the Center for Artistic Activism.

Editor’s Note: This interview was conducted in 2009, before the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United and before the Occupy movement. In 2016, one of the key issues in the US presidential primaries is the role of money in politics. While Billionaires for Bush was ultimately unsuccessful in stopping George W. Bush, it was part of a move toward the general awareness of the huge and detrimental impact of money in politics, and has helped to push the nation toward the desire for anti-establishment politicians – for better or for worse. — Sarah Halford

Stephen Duncombe and Steve Lambert: Can you give us an example of something that worked – why it worked and how do you think about it?

Andrew Boyd: Billionaires for Bush. Our objective to defeat George Bush was to persuade swing voters in the states that were going to determine the election; to take people who were leaning towards Bush and give them some compelling reasons not to vote for Bush, or people who were on the fence to give them compelling reasons not to vote for Bush, or strangely kind of humorously compelling reasons to vote for Kerry. That’s what kind of impact we wanted to have at the ultimate level.

We also had a number of copycat chapters – participating other entities within the brand, or within the “participatory large scale prank” or whatever you want to call it. It was a quite extraordinary rate of growth and level of enthusiasm. We started with a chapter in New York and another chapter in LA, and maybe a little scattering of groups left over from the election in 2000, and it grew to up to one hundred chapters. Thirty or forty chapters participating regularly and a different set of thirty or forty of that hundred participating regularly in our national days of action.

So, in terms of level of participation, level of enthusiasm, the capturing of media interest, and in terms of our strategy to put this meme Billionaires for Bush: that phrase, that name, that website, it was all the same idea. The entity “Billionaires for Bush” was embedded in this idea that Billionaires’ interests are aligned with George Bush. If you’re not a billionaire, or maybe you want to think about whether or not your raw economic interests are aligned with his policies, here are all these funny ways in which they are not – that George Bush is the CEO president, and that he is the handmaiden of the corporate elite, and you are not the corporate elite, therefore you may not want to vote for Bush. That is embedded in Billionaires for Bush.

S&S: In terms of tangibles, measurables, did you think about those when you were constructing your campaign? That is, copycat chapters capturing press – did that factor in for you?

AB: Yes completely. We learned some lessons from 2000 and other campaigns.

S&S: Could you talk about that? Were there failures and successes you learned from? And what were they?

AB: There were both, probably. We realized that if we had a really strong concept we would work up into compelling materials. We came up with this idea that we called the “Million & Billionaire March” which we did at the Republican Convention. We realized that if we could come up with some really strong compelling concept that was right on the nerve of where the media was gazing at that we could, in a clever, concise way of saying something that everyone was thinking but that was having a hard time saying, we could or at least get a crystalline object with which to riff off to talk about some political economic critique that was a little bit difficult to bring up that people would respond. And if we created a participatory structure that people could follow and that was fun to follow – people would follow. So we learned that fundamental lesson. So we just took that to another level in 2004.

S&S: So, you know that people want to get involved in something that is fun to get involved with, and Billionaires for Bush is an art project in many ways. How did you think about that when you were creating this project, and how did you maximize it?

Andrew Boyd: Ok well, a lot of different things. We created it to be fun — something that was easy and that everyone could participate in. Go down to Ricky’s or go down to store and grab a fake mink or get some bling from Ricky’s or pull their old tuxedo out from being some groomsman from some wedding out of their closet and dress up and bling up – that was something that people enjoyed doing; we made it so they could personalize it, make up their own character. Their own name. We had a core set of materials that were very strong so that people could recognize the intelligence and the humor and relevance of the work, which would sort of hit this nerve and describe the world in an ironic way. It added a sort of charming lens to the hypocrisy evident to all of us so that people could find voice in that artistic act.

And it had a lot of dimensions – there was street theater, there was online participation, parties, a lot of ways of expressing that. We had a do-it-yourself kit that sort of lined out all this stuff, but also left a lot of room for creative collaborations. We just kind of took that to a more deliberate, operationalized way through an online do-it-yourself kit – which had an online or start your own chapter kind of structures with a “come up with your own character” and “come up with your own name” and “here’s our initial set of slogans – come up with your own, tell us about them and if they are really good we’ll add them to the core set and then we’ll do a 1.1 and a 1.2 and a 2.0 version of our materials.” That kind of thing. Very strong materials that people want to participate in but degrees of freedom for their own deliberation and for their own creative sense of ownership.

So in terms of getting that meme out, we had pretty excellent exposure to the point where we became the reference point – where someone might be writing about something else and say, “the comical Billionaires for Bush, here are some actual billionaires who are supporting Bush and here is why…” They might just write an article offhand, not contacting us at all, but referencing us as part of the landscape.

But politically, we have absolutely no metrics. We have a few anecdotes about sort of little moments when we would have interactions with people and they would have these ah-ha moments, but we really don’t know what was going on inside their heads even. We have no metrics for persuasion. We have no idea if we were successful. We have no idea if we persuaded a single voter.

S&S: And in the grand scheme you were not successful because George Bush won, right?

AB: Yes, for our largest objective yes, we failed massively. Obviously we were .0001% of the various factors that were relating to that outcome. In our secondary set of metrics, because I had to justify this to some degree to get funding and rally the troops and to sort of make my own year of blood sweat and toil and everything sort of feel worthwhile to me – in the second level there was a lot of measurable metrics that we knocked out of the park. Like if you were going to measure by column inches you know newspaper real estate that we captured it would – well, I don’t have an actually final number but it was like, you know, three hundred articles.

S&S: It was feet. It was column feet.

AB: Column Feet. Yes, it was feet. Thank you. Call them meters. That’s right.

We had the sum of capturing media attention, column inches, number of appearances in TV and radio, ability in which the meme penetrated the broad public discourse around the election, and enthusiasm of participation in a couple different ways – bringing people in who were previously turned off of politics, who didn’t feel there was an outlet for them whether they were too creative and most of the politics was too straight forward and lock step and boring. It said, ‘I care about what is going on in the world but I haven’t found a way for me to participate in a way that suits me.’ So this created that space for them. It was also a way for creative professionals – web designers, graphic artists, professional hollywood composers, what have you, a way for them to mobilize their high level talents that they get paid serious three figure per hour kind of corporate dollars for – for something they actually believed in. And that was huge. Not only did it bring all this pro-bono sweat equity kind of stuff into the campaign, but it gave these people who are very valuable, relatively powerful people in the culture because of their ability to craft message and engage in that battle of hearts and minds – whether they are doing that to sell Coca-Cola or to question George Bush’s sort of populism. They would now have an experience using their high level talents for something good so that hopefully they could then replicate that in other settings afterwards.

Then for a younger set of activists – for a set of savvy, cleverly designed campaign gave them a deep experience on how to do that sort of thing so that maybe they could continue as activist or intermittent activists or civically engaged in some way. This provided them a model. Not a blueprint, but guidelines or rather training in our to run that kind of a campaign. Those are all second tier metrics that I feel like we succeeded in greatly.

S&S: You brought up metrics, brought up columns, talked about numbers – this is obviously something that you think and care about. But, why? Why not just do it and see what happens? Why waste the energy thinking about how you can get all these other people involved when you can just do something really big – you know put it all into one big event. That you controlled and it was just you.

Andrew Boyd: Well, OK, there’s the obvious answer. Why do we care about results? Because we want to change the world.

S&S: Why the tangible results?

“you want to reach those goals. To do that, generally it is good to have a strategy, a theory, a hypothesis about how to get to those outcomes“

AB: Well, that’s actually a good question. There are a lot of ways to change the world. From very tangible – like defeating George Bush and rebranding the Republican party so that it is seen by a broader swath of the public more accurately – as a party that is catering to the interests of the rich rather than catering to the interests of the public, which it is not. It was those outcomes we were driving after. You want to succeed with those outcomes – you want to reach those goals. To do that, generally it is good to have a strategy, a theory, a hypothesis about how to get to those outcomes, and to have those hypotheses previously tested in various settings so that you have a wealth of experience under your belt. That it is a relatively well tested theory; that you are then going to know enough about what you’re doing to judge whether you’re on target or not and to adjust course necessary.

S&S: That’s interesting, can you say more about that?

AB: Let me also say that it is that for us to achieve our artistic objectives and our political objectives – political objectives are what I just lined out – but to achieve those political objectives it just wouldn’t do to just have some huge event that I controlled and just do it. That wouldn’t achieve anything. Like the results that we wanted to achieve and what we did achieve – which was to foster this movement if you will, this mini-movement, this expanding mutating participatory artistic project and campaign in the political sense – and that required an open architecture that required us to let go of some control to a certain degree.

People would take ownership of it, see it as their own, reinvent it in small or large ways and then stay with in through the whole year and sustain that interest and enthusiasm. It became one of the most beautiful aspects for me, to see this set in motion, that I was sort of the prime mover of getting it to mutate and grow in ways that I previously hadn’t imagined. Within some other circles of thought I think that this is called emergent behavior. Emergent properties, that are not explicitly thought of or designed in from the beginning. A structure fostering or encouraging emergent behavior. You know, you Provide the DNA – the crystal that sort of takes on a shape – like you somewhat had in mind but it now has its own shape. That was the most beautiful aspect of the whole thing; actually both politically necessary, and for me as an artist it was the most beautiful thing about it.

S&S: As opposed to the static like…

AB: Like a well executed static plan that I sort of assigned roles to that and then looked pretty much like what I had in mind. We modeled it and then helmed it. There were other people that sort of became core players. We all sort of became helmsmen of this larger thing. There was this very interesting mix of democracy and dictatorship.

S&S: I think it is called Leadership.

Andrew Boyd: “We modeled it and then helmed it. There were other people that sort of became core players. We all sort of became helmsmen of this larger thing. There was this very interesting mix of democracy and dictatorship.”

Steve & Steve: “I think it is called Leadership.”

AB: Leadership OK. Well there is leadership in the art space and then there is leadership in the political space. In the art space, you call it the Director or the Auteur, or the visionary or the producer, and I had a little bit of all those roles rolled in. In the political space you call it leader or executive director.

In terms of rolling out new ideas, generally if I feel like it is the right idea and the right time then I want to concept it out to a degree, like a one pager. Then I want to get together people who I really trust, whose sensibilities I know, to then knock it out one step further. Like flush it out with some visuals and some basic set of materials. I call that the Beta Version. That is very compelling to people. And once you get that out they can look at the visuals, the one pager, the beta version of the webpage, that kind of thing. The core suite of materials. Then everyone in that room agrees, then you can have a launch party, and then people know what they are getting themselves into. You don’t want to bring in a wider group of people until you have that suite of materials and concept nailed down. I think. That has worked for me well.

S&S: Is this formal thing for you — where you sit down and by yourself or with a group in a cafe and say, “OK, today is evaluation day. Every Thursday is going to be evaluation day, or is it like more on the fly?”

Andrew Boyd: It is something I’ve come to by a zig-zaggy trial and error and I wouldn’t call it formal but Quasi – Formal. That means, I recognize that process and engage myself in it. There is not a worksheet, and it’s not like I have a calendar with stage one, stage two, stage three. Both in the 2000 and 2004 elections, that was sort of the process; I put a one pager together, pulled together a small team, and knocked it out and then went to the next stage. Three stages if you will.

S&S: What about your reflective process? What if the beta test didn’t work?

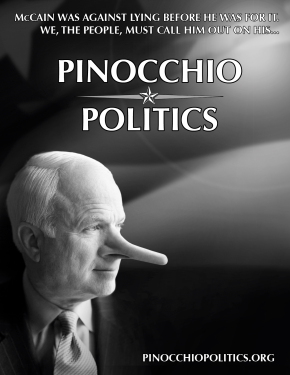

AB: On the fly. There is not a checklist or set of questions or an evaluation form or anything. There might be a debrief. Like I did that at the end of this Pinocchio Politics campaign at the end of the ‘08 cycle and we sort of gathered some of the core people and tried to see what worked and what didn’t. I had my intern Duncan write up a case study on the most useful lessons to be drawn from the Pinocchio Politics thing.

S&S: What is the complex or roundabout answer to why you thought about case studies or column length?

AB: Well, these case studies or efforts we’re engaged in are in that overlapping place between political action and art projects. Sometimes more on one side of the spectrum sometimes more on one side of the other. There are different metrics for the political outcomes and for the artistic outcomes. Well I don’t know if artistic outcomes is the right answer – maybe artistic experience. There is the a certain satisfaction in making in good design and a satisfaction in that heightened experience.

S&S: You mean like, creating the system and watching it play out —

Andrew Boyd: Design in a number of levels. But what I am looking at is metrics and how they are different in the artistic realm and how they are different in the political realm, just for a second. So there is the heightened experience, good design, beautiful objects that you create, and seeing this organism take on a shape and flavors of its own. That is part of the artistic experience. So yes, there were artistic outcomes. We made beautiful stuff, really beautiful stuff – both photographs that were taken and of people’s theatrics – that was beautiful. Our signs and designs, and graphics was beautiful – there was a real elegance to the design. People had powerful memorable, life changing, lovely experiences that were all outcomes. These are very much intangible metrics but they are outcomes of its success.

So it can fail as a political project but still succeed as an artistic project. Billionaires for Bush succeeded as an art project. It had all of these in ways that are documentable in term of photographs, and artifacts. An ongoing community was built, personal relationships, and life changing whether they were uplifting moments that people carry around with them for the rest of their lives or whether they were educational ah-ha moments, or whether they were finding a way to reclaim America – re-engaging in the civic space. These were outcomes; some were political and artistic, but I’m trying to isolate the ones that are much more art ones. And then again some can succeed in the sense that, ‘WOW, that failed miserably but I learned something important about how the world works or how psychology works, or how visual perception works, or what I like and I don’t like, or how people respond to and what they don’t, or what the media will bite and what they won’t.’

So, there are a lot of ways things can succeed. That is some of the complexity I wanted to bring in, beside the fact that there is the first tier of political outcome and the second tier of outcomes. On the first tier we had no metrics on the second we had a lot of metrics.

S&S: How did you know if it didn’t work? You brought it up the Pinocchio Politics for example. Which coulda, shoulda, woulda, taken off like Billionaires for Bush…

S&S: Or Lobbyists for McCain. Maybe they’re not great examples because they didn’t hit the bar you set so high for Billionaires for Bush. But maybe things that you think is going to work and then they fall flat on their face. What happened?

AB: Let’s talk about those two campaigns. We’ll start with the Lobbyists. We started really late. Lobbyists for McCain was a 2008 version of Billionaires for Bush, a campaign very much in that style, where lobbyists were the narrow special interest that were backing McCain. It was a fake campaign, composed of lobbyists, and there is a strong basis in reality for that claim because there was at least at last count 137 lobbyists working on McCain’s campaign. One of his close allies said that if there weren’t lobbyists the campaign would be half staffed – this is a strong Republican GOP saying that, so you know and there was a lot of dirt coming out about this lobbyist connection. He was vulnerable on that, we thought, and we added to that meme. So that was Lobbyists for McCain.

Basically in terms of outcomes it didn’t really get any traction; almost no coverage in the press, a little bit of online attention, no copy-catting, whatever. One was problem was that we started late in the process. Billionaires for Bush – we started in October of 2003, so when we launched in January we already had a lot of pieces in place. We hit the early Primaries so we could build on the craziness of the July-August conventions. So we had a long arch to build up from. Another thing was that we had money then – we didn’t have any money for Lobbyists. Third thing: there was a nice alliteration in Billionaires for Bush that Lobbyists for McCain didn’t have. And, Bush was a much more polarizing, hated figure that had more comic potential – he was much more of a straight man in a way. There was such a reservoir to knock this guy off of his throne that we could tap into in 2004.

S&S: Well, a lot of these categories we could throw these reasons into have to do with timing in a way.

AB: Yeah, timing and the target. There was something, just, high-concept in Billionaires for Bush. Lobbyists for McCain felt prosaic. The other thing is that we abandoned it half way – we had this great website and then we went to the convention the money fell through, and we said ‘fuck it’ and we jumped ship to this other campaign – Pinocchio Politics. I just wanted to come up with something; my strategy in ‘08 was just to keep throwing things up against the wall and see what stuck. So we just jumped from lobbyists. I didn’t like dressing up as a Lobbyists so much. There was billionaire fatigue. Like we wanted to trump ourselves; you want to come up with the additional twist that makes it interesting not only for you artistically, creatively, and intellectually but also interesting to the press and stuff.

The big show in ‘04 was talking down Bush. The big show in ‘08 was the rise of Obama and Sarah Palin. So, we had put all this Lobbyists for McCain website together – headed for the convention – and boom Sarah Palin was a nuclear bomb on the media scene. There was a distraction. Nobody cared about McCain anymore. So then we were thinking – should we do Palin for President in 2012? Is this really a stealth campaign? We decided not to go for that because everyone else was already piling on Palin.

S&S: You did cycle through these things to see if they worked. What was your criteria to see if they worked? What were the steps?

AB: Someone approached me with this idea about doing a Pinocchio Politics because McCain was being called out on all of these lies. He was running this really horrifically dirty campaign and these terrible TV ads and just falsely claiming things again and again and again, and he was starting to be called out in the media for it. Ok, so then we were like, let’s brand McCain as the liar. The term Pinocchio Politics and McLiar seemed viable, like it had some traction. It was a trope or a flame that would continue through the election. It would include Palin in a supporting role. It seemed flexible and supportive enough that it could work. It seemed much better than the Lobbyists for McCain at the time.

S&S: Let me ask you this, because you’ve mentioned press – column inches and that kind of thing – have you had a project that you would say is successful that didn’t have press or would you say that press is key component?

AB: Not necessarily, but in a lot of the projects I design, that is sort of a key component. Certainly the Billionaires for Bush. This project wouldn’t. This project could just work as an internet phenomenon, ideally, that it would have traction on the internet. It would have a horizontal exposure. It wouldn’t need to be picked up in what we think of as press.

S&S: That is still thinking mass audience. Have you ever done something where it’s ten people. Like really intensely changing ten people. What is the advantage of a mass audience versus smaller audience?

AB: If you’re just focused on ten people then you don’t really have to market yourself in a certain way. It kind of gives you a certain level of freedom, intensity, and intimacy and community in and of itself. It is sort of not having to represent itself outside of itself. It is for itself.

There is an authenticity thing. If I believe in what I’m doing, if I think I have some handle on the truth, if there is some piece of information or perspective that I think is important, then I should want to share it as widely as possible. Maybe not initially, but maybe work my way to a place where I can share that as widely as possible. There is a certain balance in scale and dilution of affect or loss of control so you design things to have the largest impact that they can. Now there are other realms in my life where I do do that – I don’t campaign around recycling, but I do recycle.

S&S: Why are you wasting time on this culture and performance stuff – why not just write books?

AB: I do write books.

S&S: But not just write books or register people to vote?

AB: That’s a good point. To reflect on all this hoopla, hijinks, and media attention and memes and column inches and strategies for branding and blahblahblah – sometimes I just think that I should just be registering people to vote.

S&S: Then, why don’t you go do that?

AB: Well, this keeps me interested. Yes, I’m good at it. I have developed a lot of skills doing this. I can get paid to do this creating media political artifact type thing. I like building up a portfolio a repertoire of these things and they become richer and richer set of reference points to perfect the craft. As all humans, I’m partly a creature of habit. I’ve been doing this, this is the community, I know the sort of the lay of the land, I know the people in it, so here is a lot of that. Even the voter registration campaigns there are parties to the polls. So it’s still community building – using cultural events to encourage voting.

S&S: Is there something uniquely valuable about using culture?

Andrew Boyd: Well, I think there is something affirming of our humanity in culture – in the community building side of things. A connective tissue, quilting all of us together and creating meaning as you strive for these outcomes. That is different from operational politics – when you’re just trying to do turn out or get numbers or turn people out to a rally.

I like the movement culture because there is so much about movement building that is organically and instinctively cultural – like community or of stories that are created or history that gets written in the political process of people trying to change the world. Meaning gets created whether you have puppets there or not. There is a cultural dimension in any case – right? There is a quote I used in The Activist Cookbook from one of the Irish revolutionaries: “The movement isn’t really real until the people take it up in song.” This is how people take it into their hearts.

S&S: One final question: you said you worked with these graphic designers that wanted out of their jobs, or wanted something more valuable out of their day jobs. You seem to have no hesitation about using the Master’s tools —

AB: Yeah, I don’t even engage in that debate.

S&S: What you think about that? You’re using this popular language that has been successful. Why not try to develop your own as opposed to borrowing?

AB: OK, Well the simple answer would be because it works. I don’t think there is anything counter revolutionary in using in some of these tactics and artifacts, to be honest.

I’ve never been a fan of the anti-aesthetic. I like lyrics I can hear and never liked zines. I’m not about making it more difficult than it has to be. I like to make difficult and important ideas as accessible as possible. Not making their presentation difficult. Shock for shock’s sake is immaturist and what’s the word – je jeune – an adolescent or an activist that hasn’t matured. It is a valid artistic strategy but it’s a poor political one.

If it is authenticity that you’re looking for, there are ways to have that authenticity in the smaller spaces of life. There are ways to sell out that don’t have to do with using those tactics and language. There are ways to sell out where you compromise your politics, where you pull back from what you really believe in order to be more strategic; that is part of savvy politics. That is part of the dance. I’m not saying there isn’t ample opportunity for your politics to go wrong, but that is the dance in which the problems lie. For me, it is not so much the methods. But if I am going to run a campaign, I’m going to use the best techniques out there.