Going back to the early days at the March on Washington…to watch people respond to us as we walked by was…people just lit up. It was 6-7 years into the epidemic by then and people were just looking for something to do that was positive. I remember chanting: “we’ll never be silent again!” And the people on the sidewalk initially thought that maybe we were yelling at them, but then they realized: no, we’re the “we.” And by the end of that weekend everybody in town was wearing Silence=Death t-shirts and buttons. I looked around and went, “Oh my god. This is something. This is going to be a movement.”

Ron Goldberg was a member of ACT UP from 1987-94. During that time, he served on the action committee and took up the role of “chant queen.” Inspired by his love of theatre, Goldberg helped to make ACT UP’s demonstrations the performative masterpieces that are still remembered, and emulated, today.

*Special note: Because syncopation is important for Goldberg’s chants, readers can find a guide to their rhythms at the bottom of this interview.

Sarah J Halford: Let’s start in 1987 – the year that started it all for you. Tell me a little bit about who you were at that time, what your interests were, and what brought you to ACT UP.

Ron Goldberg: I was an actor-singer-waiter who moved well. I was doing auditions, I’d been in the city 7 years, and I’d gotten my equity card, but I had sort of hit a rut. My acting career, which is what I saw myself doing, was not panning out. It sort of came to this point where there was this decision of – I needed to get involved with something. There was so much going on and I needed to connect to something larger. So, I stumbled into ACT UP, as a lot of people did. I was actually at a meeting for something else. There was going to be a big march on Washington in 1987 for gay rights, so I went to this meeting at the Center on 13th street, which then it was the Lesbian and Gay Center, now it’s the LGBT center, and it was really terrible. It was like a bunch of us in the corner, and the organizer was saying how there’s not enough people and how it’s going to be so much work, and I thought, “Oh well this sounds great.” But then, ACT UP was holding another meeting in the big hall. I’d read about ACT UP, so I thought, “Oh, let me check this out.” It was electric. It was astonishing. It was the community I always wanted.

SJH: What was the difference between the first meeting and the ACT UP meeting?

RG: One, it was the energy. The energy was incredible, and the amount of people, I mean it filled up the whole room. It was an insane conversation about what to do for the gay pride parade; there was this big argument about a proposal to do a sort of concentration camp-style float, and people were like, “No! That’s not how it should be! We should be carrying coffins! These kids today, they don’t know that this is about death!” And another was like, “No! This is about living with AIDS, not dying!” There was this back-and-forth, and it was just heated, smart, electrifying, and riveting. I stayed in the back for the entire meeting. And I really wanted to get involved, but I happened to have gotten a reading for some terrible show, and I was in rehearsals for that, so I couldn’t attend. And for the first time in my life I was dreading going to rehearsals, because I really wanted to go to this meeting. I’ve come to realize, looking back, that a lot of the things that I went into theatre for – community, trying to communicate important issues, make an impact, and that intense closeness – I was getting that in ACT UP.

SJH: And then as you started to get more involved, you became ACT UP’s unofficial “chant queen”?

RG: Oh, I was official!

SJH: Oh! You were official! So how did that start then?

RG: Well, it was sort of like, everyone did what they were good at, and for better or for worse, I’m a good cheerleader. Not that I ever did it in the “go football team” sense, but I had energy, I was fun, and it was just something that I took to. I knew that I could get people going.

Part of what we were doing was so much in people’s faces. I knew that if I yelled, 50,000 dead from AIDS! Where was George?! And did it with a certain intensity, and people joined, a) it picked up people’s spirits and b) it also gave a focus. Chants are also sound bites that people hear over and over again. So, if they stuck a microphone in your face and asked, “Well, why are you here?” You would answer “Because healthcare is a right!” So chants provided soundbites, but they were also about keeping the energy going. It’s much easier to chant when there’s a little syncopation, or a little rhythm. One of the things that I’ve noticed when I’ve gone to the Occupy and the other protests recently, it’s like everyone chants in squares (beats on the desk in 4/4 time) and there’s no place to breathe and there’s no place for creative rhythms. But it’s much easier when you go: Healthcare is a right – healthcare is a right.

SJH: Right, so the musicality of the chant is inviting?

RG: Exactly! It’s electrifying.

SJH: So, if you were to define what makes a “good” chant, in your opinion, what would that be?

RG: I think it’s succinct, it captures what you’re trying to say. I think that it’s got rhythm – rhythm is really good. A place to breathe, and something that involves the crowd. You know, the call and response ones where you could alternate the phrases were great. I think those are all key points. And for us, a lot of it was what we could do with humor; a big part of our arsenal was ridicule.

So – this one isn’t a brilliant chant, but it was fun to do – for instance, Cuomo Sr. had a bad AIDS record. Mario kept promising us things, saying, “Oh, I feel you’re absolutely right” and then he would do nothing. And one year he actually said, “You’re right, I won’t be doing enough, but next year, come back.” So I came up with a chant when we went up to Albany that went: You said come back in a year? Time’s up Mario (snaps) we’re here! And that humor – you know, we didn’t do it a lot, but it was fun! It’s got this attitude that’s much better than something like: They say, ‘don’t fuck’ – we say, ‘fuck you!’ I used to go crazy with chants like that because anybody who says that is not getting onto any television screen at all. And today, there’s the internet which is much less censored, but at the time it was like, why say a chant that isn’t going to get your message across?

SJH: Now that you’ve been through the process with ACT UP, what are your thoughts on recent movements like the Arab Spring, Occupy, or #blacklivesmatter?

RG: I think things have changed so much. I think there are hints at what we did, but what you’re able to do has changed so much. We had videographers filming all of our actions because we couldn’t trust the media to put out our stuff, so we put out our own. But, I often think that movements now need to get out of those square chants.

SJH: Like: Hands up – don’t shoot?

RG: “Hands up – don’t shoot. Hands up – don’t shoot” – there’s no place to take a breath, though I certainly get the meaning behind it. It would be like saying: ACT UP – Fight back – Fight AIDS. But even with that, at least there’s an action there. “Hands up – don’t shoot” is like, what are you asking people to do? What are you saying? You’re taunting, and that’s legitimate, but I think a message beyond the chant is crucial for the chant.

You know, sometimes I’m asked about Occupy and why that “fizzled” or whatever, but it’s just the beginning of a movement. They got a whole bunch of concepts into the political dialogue, which is extraordinary. The idea of our movement started in 1981, 1982; ACT UP didn’t come around until 1987.

SJH: It takes a minute.

RG: It takes a minute. I think it’s amazing what’s going on, I’m very encouraged by it. The internet and social media have had an incredible impact in some cases, but it’s not deep. ACT UP had a deep connection that I would love to see incorporated into the internet strategy. Social media is a great way to get people connected, but it doesn’t build a sense of responsibility. Click activism has its limitations.

SJH: So, what’s needed to build that sense of responsibility?

RG: You have to get into a room. Get in a room with people who maybe don’t think the same way as you, but who see the same problems. It’s about building that trust, that love, that knowledge-base. Because with ACT UP, there was a lot of improvising, which you can’t do well if you don’t deeply trust one another. We had some set ideas, but there was a lot of improvising. You also need to think about the steps. You want to get a meeting with someone in power? Great. And then what? It’s great to have the end-goal of bringing down the institution, or whatever it may be, but what are your incremental pieces?

SJH: It seems like three things that ACT UP really had going for it were humor, shock value, and the utilization of the media. So, can you talk about ACT UP’s relationship to the media and how you fed into it?

RG: The other thing about ACT UP was that we had an extraordinary expertise. The people who came through that door were astonishing. Bob Rafsky, who headed up our media at one point, was the VP at Howard Rubinstein and was Trump’s spokesperson. We had a lot of people who knew the business. Our designers often came out of advertising. It was an incredibly media-savvy group, which was also because it was a privileged group. We were predominately white, very often connected white men, photogenic, and we had people like Ann Northrup, who was a producer at CBS, who would teach us how to do sound bites and who gave us media training.

SJH: What were the key things that she would say?

RG: You talk through the media. You decide what your point is, and you make that point. It doesn’t really matter what they ask you. You make your point, you do it succinctly, and if a microphone was in your face it was: don’t equivocate, state your point, it doesn’t really matter what the question is, and don’t get confused. I think that it was using the media to do something else. They’re not the audience. They are the vehicle.

SJH: So tell me about your audiences, then.

RG: It varied. I think there were sometimes demonstrations that specifically targeted the pharmaceutical companies, the FDA. Very often we did demonstrations that were essentially shows, which is one of the reasons that I attached myself to ACT UP because I realized, “Oh! It’s putting on a show! I get this!” So, sometimes the target is the institution or company or figure in front of you. Sometimes, you were at locations that were symbolic to use the media to get through to the larger public. So, sometimes the audience was right in front of us, and other times it was a bit more triangulated. I mean, look at something like the FDA. The thing about the FDA action was that we accomplished so much of what we needed to before we actually got there. So, we just had to show up and put on the show.

SJH: Interesting. What do you mean when you say that you accomplished what you needed before you arrived?

RG: No one had ever protested at the FDA. Our issue was that there were drugs that were stuck in the pipeline that we knew worked, that were tested in other countries, but were going to take 8 years for approval. We didn’t have 8 years. So, we prepared with internal teach-ins, so that we learned how the FDA functioned, what its structure was like, who was who, and what the issues were. We did trainings so that we knew how to do civil disobediences and how to marshall. We did media trainings, they sent out press packets with specific information on specific issues, who your local contact is. It was a national action, so there were people with AIDS all over the country who could then become the local angle.

A week before we did the demonstration, the information was already bubbling, so the FDA was already under the spotlight. And Michelangelo Signorile, who’s now a the Huffington Post, said that we were going to shut down the FDA, that it was going to be the biggest demonstration since Abbie Hoffman and the moratoriums against the Vietnam War. The night before the demonstration, the news was already saying that the FDA was closed. We had already sort of accomplished it. The spotlight was already on, and now we just had to put on the show so that there was footage.

If you look at the photos, we had people doing die-ins, we had people using tombstones. If you’ve seen the photos, I mean, they’re extraordinary. And it was different groups doing different things; we had Silence=Death, AIDSgate – there were certainly images that were produced, but a lot of it was also different groups of people being creative and doing their particular show.

We had all of these incredible photos all over the country after that demonstration, but the New York Times had this one photo of a protester with his head down, surrounded by cops. There was no explanation, no description or anything, it just looked like some lone person. But a year later, when they were talking about all of the changes that had happened in the FDA because of activism, there was a ¾ page across photo of activists who were in white smocks with their blood red handprints on them and the Silence=Death banner. And that’s how the image of people with AIDS changed. The media went from presenting an isolated individual to presenting an entire movement.

SJH: Let’s talk more about the FDA action. As you said, the work was already done so you just had to show up and do the thing, so what had to happen to get them to shut down the night before? How did they know that you were directly targeting them?

RG: We had an incredible media committee. For big actions like this, we took out full page newspaper ads, we did teach-ins, prepared press kits specifically for the media where we told them that this was going to happen and what we were about. We gave the media stories and people to talk to. The FDA, in a lot of ways, colored our reputation as a “threat.” Our name alone earned a certain cache, to the point that when we were around, people would come out to see what we would do. The media was staged as if we were opening a movie.

But it was a lot of initial leg work. We did the prep work and the teach-ins, and then a week before someone did an interview and introduced our story. We had our affinity groups feeding not just the national media but the local media around the country so that by the time we got to the FDA demonstration, we had the media saying, “This is going to be the biggest demonstration in Washington since…” and we all looked at each other like, “really?”

SJH: What did you want the FDA to do specifically?

RG: Well, we had (laughs) so many booklets. We had very specific demands about changing the way that drugs were tested so that access to them could be gained quicker. Our demands got more sophisticated as we went along, of course, but there were always very specific demands, whether it was the demand to bring a drug that was approved in another country to the States, or change a specific definition at the CDC because women were not getting diagnosed with HIV, so they’re not getting drugs and are dying twice as fast as men. That’s what built our reputation; not only was there this incredible force in the streets that could embarrass you, that could get headlines and attention, but it was also the detail. The smarts. We backed up our actions with smarts.

SJH: But some actions had more effect than others. Was there a specific thing that you did in this case to make the FDA actually do something?

RG: I mean, they were agog! We embarrassed them. We also had the advantage of being right. It was coming at a time when we were able to start to corral public opinion that things were not going fast enough and that there wasn’t enough money being spent on HIV drugs.

With the FDA, it’s interesting because we had this bizarre bedfellow in that Republicans really didn’t want any regulations on drugs to begin with. So, they were pressuring to ease up the testing process so that more drugs could flood the market; consumer beware. That’s not what we wanted – we wanted drugs to be tested, just tested quicker. We said that drug trials needed to be looked at as healthcare. If they couldn’t get the drug, then they would certainly die. Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t work as well as it could…

SJH: But it’s something.

RG: It’s something.

SJH: It seems like ACT UP as an organization had a lot of affinity groups that would accomplish different tasks. How did it all come together so that each of you communicated effectively?

RG: We had a committee structure, which changed over the years – I was there from 1987 to about ‘94, and the organization underwent great changes. When I first came, there were anywhere from 70-100 people in the room, but in its heyday we had 500 people weekly. And that’s the thing, we also met weekly. You have to get people into a room because that’s where you build the relationships. That’s where you communicate.

SJH: Was it in those rooms that the artistic ideas were brought up? As in, the ideas for chants and images?

RG: Well, people would go off and do. We had this central floor, which for a long time it was a very active floor. All of the planning and everything generally happened in committees. There were planning committees, issue-driven committees. I very often was on the action committee. I chaired it for a while because it was project managing and putting on a show. Asking, “what’s the theme? How are we doing it?”

SJH: Basically setting the stage?

RG: Right, and all you can do is really set the stage. I mean, what we wound up doing later on, when we got bigger and took on so many more issues, was create a setting for a demonstration and let people highlight their own issues within the larger frame. So, a thing that I learned very early was that people need buy-in. You can’t dictate exactly what it’s going to be. People have to be able to own it and feel like that they were going to be able to say what they needed to say. We had parameters, I mean, they always had to be non-violent. We also got trained. The CD training and the marshall training was incredibly important because you never knew what was going to happen. It also allowed us to improvise. Now, looking back, people think “oh I can’t believe they planned that! That’s incredible!” But really, we planned some of it, the rest is just winging it. But if you’re with the same people for years, once or twice a week, and you’re all trained with the same mindset, you can adapt. Toward the end of my run, the police sort of let us do our own demos. They knew that if they shut us down, we would cause a problem, so they just let us do what we were there to do.

The other thing was that we educated ourselves. There were constant teach-ins on drug trials, on housing issues, on the way the city is structured, the way that the state is structured, on insurance issues, on health care, and then we did Queer history, and women’s health. One of our biggest ideas was that we were all experts – to the extent that that got a little convoluted toward the end. Some people became more expert than others in an area, and either you said that that was fine or you took umbrage at it. I mean, I don’t mean to paint this as if it was all “kumbaya.” It wasn’t. It was very passionate, very heated, we had people coming from various political perspectives, and then we had people who were dying. Passion wasn’t really a problem, you know, the issue was so powerful. It was just about directing that passion in a productive way.

SJH: As a member of the action committee, what were some of the tactics that you used to direct that passion?

RG: Well, when we did our first anniversary demonstration in ‘88 we used waves. For that demo, we stopped negotiating our civil disobediences with the police because we wanted to control the situation, not them. At that time, we broke our groups up in waves, so that the first group would go out and get picked up by the police, and then the next group would go out somewhere else. So, the goal at the end of the day was, for so much of it, to get AIDS talked about and for people to understand what was happening and what was not happening. That our lives mattered, and that what happens to us matter, and that the government has a role to play.

In a lot of ways, for all of the radical stuff that’s thrown on ACT UP, we were just demanding that the government do their job – which is not exactly a radical statement. As the group evolved later on there was some tension around the idea that the problems were institutional, so maybe we should bring down the institutions. Well, that’s lovely, but people are dying and are you willing to sacrifice the lives of all of these people for the sake of a longer-term strategy?

SJH: So, circling back to the art within the activism. You had a bunch of different goals because there were a bunch of different issues within the AIDS crisis. What goals do you think that art was the best at helping you accomplish?

RG: I think it was in making what was abstract to people real. Images and propaganda can do that. Avram Finkelstein created Silence=Death, which was created before ACT UP was formed, but it was like the Bat Signal. Seeing that go up in the city was just this…everyone just stopped in their tracks and went, “What is that?” We recognized the triangle. Silence=Death seemed to resonate because yes, that was true, queer people needed to speak up. And ACT UP made Silence=Death into a performative piece.

Going back to the early days at the March on Washington. I was marching with ACT UP and it was just a couple hundred of us at the beginning, maybe. We had the Silence=Death posters and we had these incredible poster snakes that were mounted on sticks that looked like Chinese dragons going through the crowd. We had Silence=Death and AIDSGate t-shirts, and all of that created a powerful presence. To watch people respond to us as we walked by was…people just lit up. It was 6-7 years into the epidemic by then and people were just looking for something to do that was positive. I remember chanting: we’ll never be silent again! And the people on the sidewalk initially thought that maybe we were yelling at them, but then they realized: no, we’re the “we.” And by the end of that weekend everybody in town was wearing Silence=Death t-shirts and buttons. I looked around and went, “Oh my god. This is something. This is going to be a movement.” So, there is an activating piece to the art.

The other thing was that, how could we make what was happening real to people? As Vito Russo said, it was like living in an alternate universe where we were the only ones who could hear the bombs dropping. So, how do you make other people hear the bombs dropping?

SJH: Do you feel that art was an important part of that?

RG: Well, it depends on how you define “art,” of course. I’m thinking of the demonstrations where we had die-ins, where people were holding tombstones that said, “RIP. Died because people of color don’t get AIDS diagnoses” or “Died because AZT was not enough.” It’s these constant images that were thrown up. We had flyers, posters, wheat pasting on just about any flat surface we could find. It created this sense in the city that something was happening. If you were in any given neighborhood, you could not avoid the information that we were sending to you – that Ed Koch was not doing his job, that the city was not doing what they needed to do for AIDS. And remember, we were still a very small group, though it may have seemed like we were bigger. We were still very controversial, even in the queer community, and in the African-American and Latino communities, even more so.

SJH: Do you feel like it’s important to saturate all vantage points? The media, on the streets, in rallies, etc.?

RG: Maybe it looked that way, but I don’t think that we were trying to, necessarily. There were certainly images and rallies that were geared toward the masses and the media, so we looked at the places that we could create pressure.

SJH: Can you tell me more about ACT UP’s audience or audiences? What were you trying to communicate to them?

RG: Well, the group that we honed in on was the people in power; government, pharmaceutical companies, CEOS – the composite of those were the “group” that we felt were essential to reach. To them, we were at best a special interest. To them, the response was, “Who cares, really?” Reagan didn’t even say the word “AIDS” until Rock Hudson, and didn’t make a speech about it until ‘87, which was six years into the epidemic. No one gave a fuck. Pardon my French.

But the overarching message was: “People are dying, what are you doing?” And that applies to our own community, to the “unaffected” community, and to the people in power as well. But if you go back to how the queer community and people of color were written about at that time, the general sentiment was that we were somehow not the “real America” and that our lives really didn’t matter the same way. It used to drive me crazy. When Bush was asked in ‘91 about the demonstration that we did near his home on Labor Day weekend he responded with, “Well, you know, if they wanted my attention, they got it. But there was a demonstration about people who are unemployed, and that’s one that really hits home because that hits families. And that’s something I care about.” It was like… . You have these moments where you realize how “other” you really are to the people in power.

SJH: So, was it a goal of yours to get the people in power to see that they can be affected too, and you’re not so “other” after all?

RG: Well, actually, we didn’t really have time for that, so we went with the “We’re going to make your life hell. We’re going to embarrass the crap out of you, we will be on your doorstep, we are relentless, we will not take ‘no’ for an answer” idea.

SJH: The “people are dying, what are you doing?” is a very succinct, beautiful way to put it, but then it seems as if, for certain people, you have to convince them that you’re people in the first place. It’s no small thing.

RG: Well, certainly in terms of where the LGBT community is now, it would never have happened without AIDS. It completely changed the conversation, where it initially it was a conversation about sex, which everybody was queasy about. What AIDS showed was 1) you couldn’t really hide it, so you had to come out. And 2) it also presented an image of a powerful community, which is not what people ever thought that gays were.

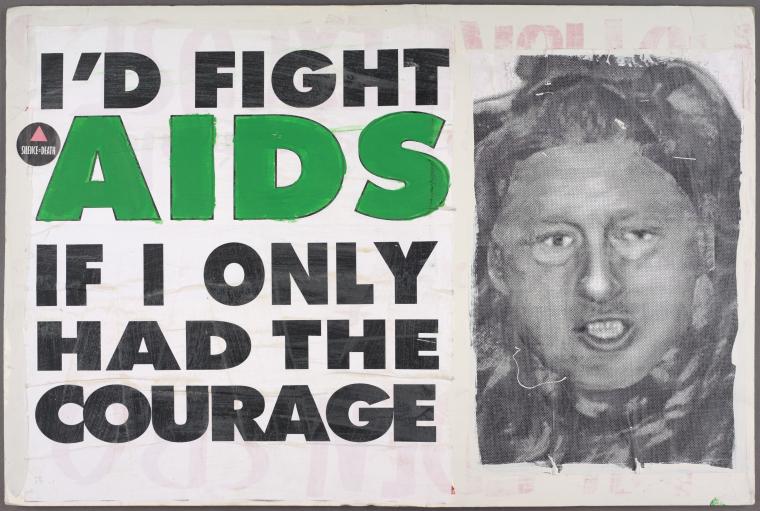

One of the things that I worked on a lot was a campaign around the ‘92 election, which was Bill Clinton. Our goal there was to “run AIDS as a candidate.” We would do a year-long campaign, but it wasn’t for a candidate, it was for an issue. We had this great, “What about AIDS?” poster. We would send these to all the other local ACT UPs so that when a candidate came around, people would be there with that sign. And the idea was – even if people didn’t talk about AIDS – it worked as a prompt, and if it got into a photo, it said exactly what we needed to say. And it did work as a prompt, we did get them to start talking about it because we pestered them until we got Clinton to promise to have a person with AIDS speak at the convention, it’s how he promised to make an AIDS speech during the campaign – it took him a long time, but he did. It’s how it became an issue that was brought up during the debates, none of which would’ve happened, had we not done that.

And we were relentless! Any time a candidate was anywhere, there were at least a couple of ACT UP people to yell and scream. What happened one time was that there were a couple of people in the snow, and CNN was there, and one of the activists yelled, “Clinton – come over and talk to someone with AIDS!” And he couldn’t say no with the camera going, so he came over and did the “I feel your pain, what do I need to do?” schtick that he had come up with during his earlier confrontation with Bob Rafsky that ran in the Times for over a week. They had a big face-off during the New York primary and it became this huge story. Being relentless helps.

SJH: Back to the chants. Can you think about a specific example when a chant that you suggested was particularly successful?

RG: Sure. There was this moment when we were up in Albany with Cuomo. We had just gotten off the bus, and Mario was doing his Mario thing, which was that he would come and talk to you saying, “What do you need?” The cameras were capturing it, and I realized that he was co-opting what we were doing for his own gain so that he looks like “sympathetic Mario.” So, I burst into a chant that was like, People are dying – what are you doing?! Everyone grabbed onto it because they also realized what was going on, and we then commenced into a die-in right then and there. Mario had to flee because he didn’t want to be seen stepping over the bodies of the people there.

Another example: we were at an abortion rights march, I don’t remember what they called it at the time, but it was a march for reproductive rights. It wasn’t an AIDS march, but again, it was part of understanding the connection of issues. A bus load of us went down because it was important that there was a queer presence at that rally; we wanted to create a safe space, as the movement had been very anti-lesbian. So, as we were marching, we’d go, ACT UP, we’re here! We’re loud and rude, pro-choice and queer! A lot of the women joined us, and again, our crowd expanded. For me, what was always very satisfying was when we were able to reach out to the people who were watching us and create this place where they could join. That was extremely powerful.

SJH: So a successful chant unites people together, it’s catchy – so maybe it gets stuck in people’s heads for a few days, and it’s a good soundbite for the media, something that’s unavoidable because it’s loud and repetitive.

RG: Right, and because it says what needs to be said. And the other piece is that it ignites passion, whether it’s fun or it’s anger. I mean, it does, chants just connect people.

SJH: Have you ever been able to connect a chant or a die-in, something that’s performative, to tangible change?

RG: I think there are larger actions that did, but it’s never one thing. Part of ACT UP’s thing was that we were relentless, for years, we just kept coming. Maybe there was something that changed someone’s mind out there, but there were a lot of ACT UP’s stuff that disappeared without a trace until the footage comes out in someone’s movie.

The Ashes Action is an example. This was again ‘92, and we went from these symbolic die-ins to actually bringing bodies. The Ashes Action was inspired by David Robinson, who was an original member who had returned from California after his lover passed away, but he came back to ACT UP because he promised his partner that he would do something and he wanted to dump his ashes on the White House lawn. That created the Ashes Action, where we went down to Washington – the quilt was still there – and people brought ashes of their loved ones. There’s incredible footage in both How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger of these ashes going over the fence and people wailing, weeping, crying. And no one reported it.

SJH: Why? Was it because it was such an extreme action?

RG: I truly don’t know. But two weeks later, someone in the group had died whose thing was, “bury me furiously.” That was the first political funeral that we had, where we actually paraded the body through the streets of New York to the Bush campaign headquarters the day before the election. There were many political funerals after that, because it went from symbolic to the real thing. But those? I don’t know if they had any impact on change. Part of this was also – we did things for ourselves, we did things to bear witness, and sometimes we did things to make us feel better, to scream, to just let it out.

SJH: An activist catharsis.

RG: And it was so needed.

SJH: We’ve been talking about successful actions, but can you think of a time that an action was just a total failure?

RG: Oh yeah, for sure. My first arrest was total failure. It was 1987 and we were at the UN, which is a terrible place to demonstrate because a) you can’t get near the UN – they put you in the park, which is surrounded by very tall shrubs, so you’re just sort of serenading yourself, and b) this was the last civil disobedience demonstration that we arranged with the police, who, by the time we took to the street, stopped traffic three blocks south of us. There were no pedestrians. We were just shouting at nobody. They were in charge, so we lost control.

Oh, I just thought of a brilliant chant. It was Stonewall 20, which was 1989. ACT UP had planned a march that was going to go from Stonewall up to the big rally that was in Central Park. We didn’t negotiate with the police, but we needed thousands of people to make sure that we could move. I was marshalling and cheerleading, you know, chant-queening. We met at the Tiffany Diner beforehand, and I was sort of freaked out about what we were going to do if penned us in, what were we going to do if they didn’t let us go? That’s when I thought of: Arrest us, just try it! Remember Stonewall was a riot!

And that’s exactly what we decided to do. We got to this point at 14th street where we had taken up the whole width of the street, and they wanted us to constrict into one or two lanes, and we refused. Our head marshalls told them that they had better let us march or they were going to have a couple hundred thousand queers uptown ready to come down. While they were negotiating, I threw out the chant. Everyone caught on because it had attitude! It went, “Arrest us snaps just try it! Remember Stonewall was a riot!”

SJH: So, did they let you go?

RG: You better believe they did! also about the attitude. There was no fear. I mean, that was pretty fabulous. That was thrown out at the moment and it just worked.

SJH: I love hearing about the successes, they sound amazing, but you gotta give me another failure.

RG: Okay, okay. We had, from my point of view, the one that was the hardest and the most upsetting was in ‘93. One of our members had died, and an affinity group had decided that they were going to bring his body to Washington, and we were going to march him through the streets to the White House. Because of a timing issue, the demonstrators arrived about an hour before they got there with the coffin, so the police were all over it. Basically, they wouldn’t let us take the body out of the car, and when we started to do so, it got to me this shoving match where they were pushing the casket…it was just horrifying. The police were snickering, it was awful. We were not able to accomplish what we wanted to, but on top of it, it just brought home how cavalierly we were regarded.

And there were a couple of ones where we got lost in the sauce. We had one in Times Square that looked like we were protesting some Broadway theater because there was a conference in the Marriott Marquis Hotel, which we were actually protesting, that was nearby. There was just no connection. We also had some depressing demonstrations in the rain…

SJH: What was it that kept you going all that time? Of course you had the personal connection to it, but for some, they have the personal connection to an issue and it just becomes too much to go at again and again.

RG: Well, it did get too intense for a lot of people, but it was a couple of things. One, we were clearly having an impact, which is motivating. You could see the impact happening in real time. My first demonstrations resulted in people in power resigning. You would actually see movement; not as fast as we wanted, but you don’t usually get to see it in front of your eyes. Another reason was that the people were incredible. It was family and community and fighting the good fight. And, the stakes were crazy.

For me, I was negative, so I had a different piece of the fight, but there were people who were fighting for their own lives. Really, for the first few years, we were all fighting for our lives because no one took the unreliable tests; no one knew who was positive or negative, so we all just had to assume that we were all positive. It was so satisfying to be able to fight the power and to get some results. It was theatre. For me, it really filled that gap in my life of family, community, contributing my performing skills to something bigger than myself. I think everyone doing it realized that it was the most important thing that we had ever done in our lives.

There is a tendency to use the war analogy a lot, but we really were in the trenches together, and so that builds a certain connection and responsibility. And love. Oh, and it was also fun! It was not all grim, sometimes we had a great time. We used to do “ACT UP: The Musical” and I wrote musical numbers for talent shows. It was a funny, smart, charismatic group. Of course, hindsight makes everything a little nicer – was it insane? Yes. Were there people who were crazy or annoying or even hateful? Sure. Were there incredibly tough arguments? Certainly, and they got more so as we got bigger. But, maybe it’s the Jewish thing for me, where the generations after the war contemplated how they would have responded if they lived in that time, and I constantly asked myself, “How would I have responded to those moments when you’re called to take a stand?” And this was that moment. It is, oddly, one of the great joys, because in so many ways I would’ve traded it all not to have done it, but I was able to recognize the moment and find a place where I was able to contribute and make a difference. I don’t have to ask myself that question anymore.

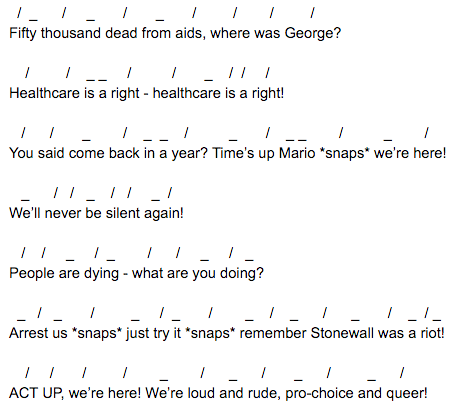

Rhythm guide to Goldberg’s chants. ( / ) indicates a stressed syllable, ( _ ) indicates an unstressed syllable:

You must be logged in to post a comment.