I think that the arts, in terms of social change, create an indirect way for people to be able to speak and express themselves. So, you can use theatre, spoken word, visual art, contemporary art, dance, movement, to relay your message, but you can also involve the people who need to relay their messages in order to explore the outcomes and solutions in a more intense, deeper way.

Elaine Forde is a director and producer based in Northern Ireland. She has created and managed many programs with the International Cultural Arts Network (ICAN) and The Playhouse in Derry/Londonderry, all of which incorporate socially-engaged art for the sake of community building and education. In 2012, she created Street Talk, a project that uses the arts to build and repair relationships between youth and police in Northern Ireland. Forde was an Arts and Social Practice fellow of the British Council in 2017. During this time, she traveled to Chicago, Illinois to conduct research and discuss her work with the Chicago Police Department.

*This interview was conducted in conjunction with the British Council’s Arts and Social Practice fellowship, of which Forde was a fellow in 2017.

Sarah J Halford: Could you tell me a little bit about your relationship to the arts and how you came to your current practice?

Elaine Forde: So, I studied a BA and Masters in Fine Art. My work was very much inspired by contemporary art and probably conceptual art. But when I did my Master’s, I started working with communities and became more engaged with working with people and involving people in what I created. I began to curate different exhibitions and programs with communities and people. I lived in London at that point, and a few years later I moved to Northern Ireland and got a job in an arts organization called The Playhouse. Its main focus areas are art and excellence, community relations work, peacebuilding, and education; those things really merged for me, because I wanted to be able to use the arts to build bridges between communities and people, and bring the layperson into art – whether it be theatre, visual art, contemporary art. So, the playhouse was a really good fit for me.

I guess I’m a kind of catalyst. I bring people together. In terms of more professional word, I’m a producer, director of projects. I’ve worked in the playhouse for about 11 years, and during that time I managed a project called ICAN, International Cultural Arts Network, which is about arts and peacebuilding. So, we brought international artists from areas of conflict who use their arts to have an impact on their countries and communities. We brought them to Northern Ireland to share their skills with our local artists, but also to work with local communities to address issues which still come from the 30-year armed conflict in Northern Ireland.

During that project, I devised a smaller project in partnership with the Play Service of Northern Ireland, which uses the arts to enable young people who are involved in crime to explore that relationship and their understanding of crime and its impact on their life. And secondly, to build better relationships with the police. So, I guess that’s where my practice is at the moment.

SJH: For people who may not know very much about the conflict in Northern Ireland that you mentioned, would you mind talking about it in your own words? Are there effects of the conflict that you still see today?

EF: So, Northern Ireland went through a 30-year armed conflict that we call The Troubles. Since the conflict finished after the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, communities became more peaceful and paramilitary groups put away their arms and were decommissioned. But even though we’re now in a more peaceful time, there are still many issues that bubble up under the surface which cause greater division, or continue to create division. One, for instance: the police. During the 30-year armed conflict, the police were called the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and was approximately 98% Protestant.They were accused of discriminatory policing against the Irish Republican Catholic community. There were allegations of corruption between the police and the Protestant Unionist Loyalist paramilitaries. And also, the police at that time were called the most dangerous police force in the world to be a member of. So, as part of the Good Friday agreement, one of the recommendations was that the police would go through reform, and with that they would be a more fair and equal organization.

Now, our police force is more balanced and equal, but still in the Catholic community today, because of the discriminatory policing against them and their families in the past, many people still don’t trust our police, so the reputation and legacy of the RUC still continues. There’s still a lot of hatred and distrust as an outcome of the conflict.

Also, relationships between Catholic and Protestant communities are still in many ways divided, and especially amongst people living in more deprived communities: social housing is mainly segregated, so Catholic communities will live in one community, or one area, and Protestants in another. With that, education is mainly segregated as well. And both communities will have their own shops, taxis, newspapers written specifically with a one-sided perspective, so there’s still a lot of division amongst the more deprived communities. There are still great issues still bubbling under the surface, and also, I think there’s still a lot of hurt from many of the atrocities during the conflict; people are still in pain and are still grieving, and there’s still hatred and distrust from both communities toward each other because of those memories. And the Playhouse, as an arts organization, tries to use the arts in ways to explore some of the pain, trauma, division, the sectarianism that rumbles through our communities.

Pictured: Participants and a police officer listen to music during a Street Talk sharing session. Picture courtesy of ICAN

SJH: Could you describe one of your works at the Playhouse that you thought was particularly successful?

EF: So, a few years ago, in 2012, I created a project called Street Talk, which is a youth art project. It came about through a conversation with a police officer who was visiting our organization. At the time, I was meeting him about security in our building, because there had been various threats in our city within cultural organizations in that year.

SJH: And why were there threats that year?

EF: That was because that year in Derry/Londonderry, which is the small city that I work in, had been awarded UK City of Culture, so many Catholic dissidents and paramilitaries didn’t agree that Derry, which is a predominantly Irish-Catholic city, should agree to be involved in a UK British-led event. So, because of that, there were a few bombs in the lead-up, and there were warnings toward communities and people that were part of that conversation, like the Playhouse.

When I had that conversation with the police officer, I was also managing an international cultural arts program and I brought him right into our courtyard to show him an example of our work. We had four international graffiti artists working with maybe 30 or 40 young people. The police officer was really interested and asked me how I recruited the young people, so I told him. And he said: I recognize some of the tags and I’ve been trying to get my hands on some of these young people for public damage – so it kind of became a joke between us like: “Hands off! These people are mine and are working with the Playhouse.”

But I wanted him to see that the arts could create a space for young people who are involved in anti-social behavior. So, we got some funding through the police to do a pilot project working with young people who are involved in crime or at risk of being involved in crime. And we were able to use the arts to enable those young people to explore crime and their relationship with it, and their understanding of it, but also to try and build better relationships between the police and communities, especially Catholic communities.

Five years later the project’s still up and running and supported by various funders. The main idea of the project is that we enable young people to attend weekly workshops, working with artists – graffiti artists, DJs, music makers, theatre practitioners, filmmakers – to explore their relationships with crime. The young people will tell their stories about any negative activity in terms of crime and their relationship with their community, family, and school, and with the police. Then, we’ll use the art form to make that story to come alive and will help young people to devise and collaborate with the artists so that they’re creating something that’s meaningful to them and that they’re proud of.

During that journey, we’ll invite some police officers into some of those workshops. We’re trying to take these kids on a journey to think about a healthier, more progressive Northern Ireland where there’s less division and hatred stemming from the conflict. Many of these young people don’t want to meet and engage police and don’t trust the police. Many of those opinions come from the young people’s personal experience with engaging with the police on the ground, but also from their families and communities.

So, at a certain point when they’re ready to meet and engage with the police, and also have family permission to do that, we invite police officers in. We try to get them to think about the context of the workshop: what will it look like? What would make them feel safe around the police? And we plan it out together. So, some might just want a police officer to talk to them and ask some questions, some might want to show them how to create an artwork and share skills, but very often the young people will hold the police officers accountable for their actions. I think that’s really important because no policing in the world is perfect and it’s important that they can tell the police officers the experiences that they’ve had and how they think it could be better or different; share their own perspective.

That’s been quite powerful, because I’ve seen a number of police officers and teams changing how they work with young people as a result of the voices of the young people that I work with. That’s really great.

So, for me, Street Talk is about building young people’s confidence, about enabling them to have a better understanding of the consequences of crime before they commit crime. But we’re not like a school program, we don’t lecture people. We talk through things, and they more or less come up with the answers themselves without us having to tell them. They also get the opportunity to do educational qualifications and also to plan and create their own events, so there’s an opportunity for them to learn new skills. And the other part of the project is enabling young people from a Catholic community to meet people from a Protestant community, as well as the police. So, the project’s been really successful. We’ve worked with many young people from both communities as well as the police.

SJH: So, when you say the police are changing the way that they work with these young people, what does that mean? What’s different in their policing?

EF: One example: we had a young person with mental health issues who had a really bad experience with a police officer. She had tried to commit suicide and the police were the first people at the scene. One police officer, she told us, was really quite derogatory to her. And when we brought the police officers in, she had the confidence to tell the two that visited about this situation. From that, one of the police officers was able to change the whole protocol around helping young people who are trying to commit suicide in Derry/Londonderry, and especially with that young person.

But I think also lots of the young people in Northern Ireland have been stopped and searched by police, they’ve been asked their personal details and there’s ambiguity around why the police need that information. So, when an 11, 12, 13 year old is stopped by police and asked their name and address, they have the tendency to think they’re in trouble. But some of the time the police are just trying to keep track on who’s in a neighborhood in what time in case there’s a crime, or there has been a crime and they need to know who’s been around in case they need more evidence. The young people just didn’t know that and they were perceiving that behavior in a very different way than how the police actually meant it. So, I think that sort of information told to the police helps officers to understand that when they meet young people in the street they should tell them why they’re asking their name or address. It’s not necessarily because they think they’ve been involved in a crime.

SJH: So, it sounds like there’s been more than a conversation; there’s been a change in behavior.

EF: Yeah. I think that’s really powerful because we know our police aren’t perfect, we know that policing around the world is really complicated and complex, and I think that police don’t always communicate in the best way with the people that they serve. What they’re doing and why they’re doing it.

SJH: And how do the young people get involved in your program? Do you go into schools?

EF: No, not schools, directly. We work with the police and they highlight communities where there’s a lot of tensions and power relationships with the police, and also crime. So, I will then make contact with community activists, maybe schools, youth club workers, and ask them to help me to try to recruit young people that they think are suitable. But the young people I work will, I think all of them, are really quite powerful. They have a very clear perspective on what they’re doing and why they’re doing it, and how they should be treated, and they have a real understanding of when they think they’ve been treated incorrectly. That’s really brilliant. I really try to empower the young people to speak up when something’s not right, and especially to police officers.

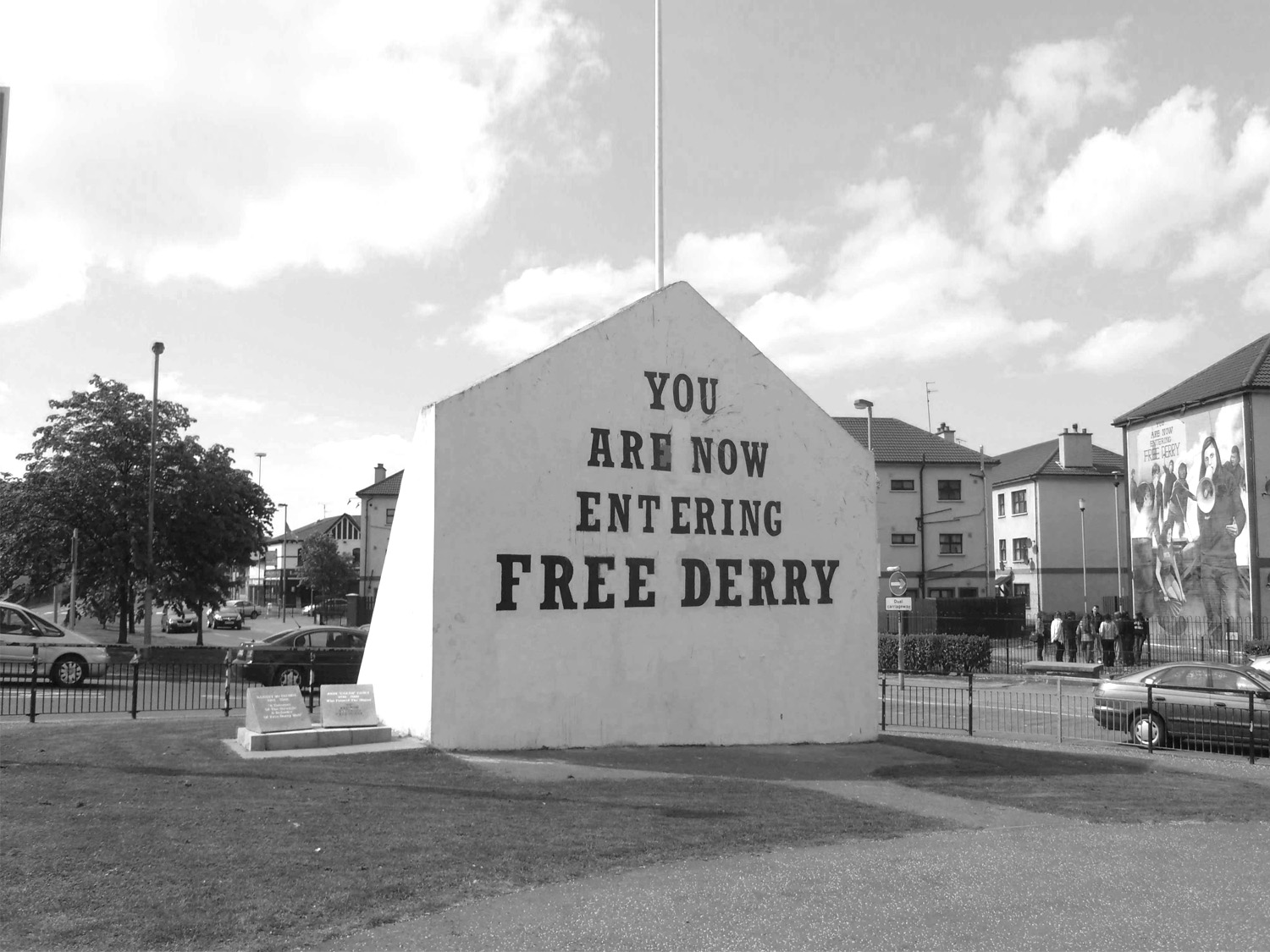

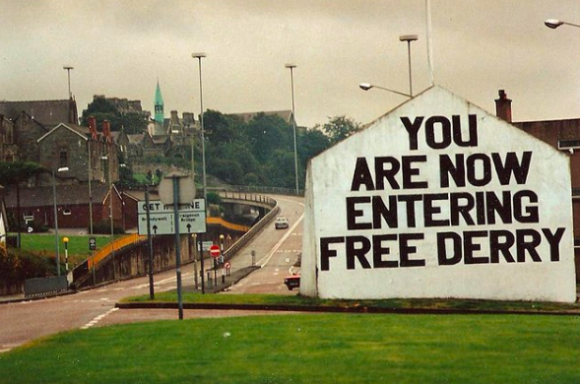

Pictured: Free Derry Corner in 1984.

SJH: Great. That sounds like a really successful example, but what about projects that haven’t gone so well?

EF: I think…hm. I’m trying to think of a project that hasn’t gone so well, and what does that mean, “gone so well”?

During the International Cultural Arts Program that I developed, I had four international graffiti artists in Derry/Londonderry. We had decided that the artists would paint on walls within the city and they would work with young people who were interested in graffiti and young graffiti artists who were really committed to graffiti as a trade. So, we decided that the artists would work on four walls. One of the walls that we identified was Free Derry Corner, which is a wall in Derry/Londonderry that is very much connected to The Troubles. It’s in the Bogside of Derry, which is a very Catholic community. Free Derry corner says, “You’re now entering free Derry,” which was a message to the police and the British army from the Catholic Republican Nationalist community during The Troubles. They didn’t want the army and the police to enter. So, they painted that message on the wall and I believe that they barricaded the area so the police couldn’t come into their community.

So, we got permission from the local community center that managed that iconic wall, that still has the same message written on it, to paint on it. The agreement was that the graffiti artists would paint the background of the wall without tampering or changing any of the lettering. Then, we agreed that we would repaint the background to its original white after seven days.

The first day when we were on site painting the wall, various Catholic Republican activists didn’t think we should have any international artists painting on that wall and disagreed with what we were doing. They hadn’t been involved in our consultation process with the organization that managed the wall and they really disagreed with it. That was very difficult because we had people who were part of a very Republican background, and we don’t know if they were part of any dissident group, being very unhappy with what we were doing. Not threatening us, but telling us that we should stop, move away, that it wasn’t our wall. So, we did paint the wall with art very quickly, and of course in my job as a project director, I’m very aware of those relationships in Northern Ireland – things can spark very quickly and easily. So, it was painted really quickly and we went back to the group that managed the wall and said that we would leave it up for something like three days and then we’ll return it to white. We asked them to negotiate on our behalf and see if those who were against what we were doing are happy with the compromise. But that was a difficult situation, a.) Because of the artists and young people and b.) Because there can be a threat that happens very quickly whenever people disagree with something that they’re doing. So, that project was difficult.

Thankfully, it blew over in a matter of days and everyone was safe and well, but I also became really interested in asking: Who controls spaces within a public area? Whose voice speaks stronger than another? And, is that right? So, about a year, year and a half later, I organized a conference called Challenging Place, which spoke about those very questions and about community ownership, artist activism within that space, community’s voice, bringing different types of people together over two days to discuss those things.

SJH: Would you consider the dissident groups to be an audience of your work? Do you make a habit of engaging with any pushback you receive?

EF: With that project, we spoke to a number of Republicans and community activists who will negotiate with the paramilitaries. Usually, we’ll get support. In that one instance something hadn’t been communicated. But it’s really important that we do try and connect in whatever way we can, communicating what we’re doing and its objectives with key community activists who can convey our ideas and aims with those other voices and communities. That’s been the only time that I’ve ever had a pushback. So, I guess we take risks, we try to be calculated about the risks that we take, we try to ensure that we are communicating what we’re doing to the right people who can address the more negative voices.

Pictured: Example of graffiti art created in a Street Talk collaboration between young people and artists. Picture courtesy of ICAN.

SJH: So, you’re currently in the States on a fellowship that will allow you to bring aspects of your Street Talk program to Chicago. As we know, the people of Chicago – especially people of color – have a very fraught and sometimes deadly relationship with the police.

EF: Yes, certainly.

SJH: When people talk about police here, they often talk about implicit bias, which by its very nature seems difficult to address. So, do you think, or at least hope, that your work can help to change implicit biases – in Chicago or in Northern Ireland?

EF: I think in Northern Ireland the work that I do has encouraged police to think about who they’re policing. In Northern Ireland, many of our communities are segregated as well, so police will know if they’re in a Catholic or Protestant community. I think enabling young people to talk honestly to the police about how they’ve been policed is very important. But I think that it’s really important that our police service remain professional. They’re paid to be professional, respectful, to serve the communities, and at all times they need to implement the idea of respect toward young people and communities and families. And, I know, obviously that’s really easy to say, but I think that the work that I do in Northern Ireland contributes to that.

In Chicago, it’s very different, I think. I’m here for such a very short time, and I’ve had some conversations with the police about the communities that they , and I hope to have some more conversations around the idea of discriminatory policing, even though people will have implicit biases. I think in a two and a half week period it’s very difficult to make a real change, but I’ve seen it happen in Northern Ireland, and I think that the arts can definitely contribute to a longer-term change. It will take many years, and I think there needs to be a change within police departments, in terms of their makeup and training, and it’s really important that the police know that they’re serving people. They’re there to protect everyone, they’re there to serve everyone, and they should be doing it with as much respect and humility and honesty as they can, knowing that each person really matters.

I’ve watched some really horrific films about the young black people that have been killed in Chicago and in America and by the police, and I have just been dumbfounded, upset, annoyed by some of the things that I’ve . But again, I think that the police need different training, different support. They need to think about weapons in a different way. Like in Northern Ireland, many police officers that I work with have received death threats, which is common, especially from paramilitary groups. An officer that I worked with had a bomb put under his car a few years ago, and that’s just very real in the context of Northern Ireland. But our police officers are not taught to shoot to kill. I think that’s very different .

SJH: So, what is it that you’re hoping to get out of this collaboration with Chicago?

EF: There are a number of things. I’m keen to share my background and the work that I do with communities so they have an understanding that things can change. There are commonalities between the conflict in Northern Ireland from 1968 to 1999 in terms of discriminatory policing and alleged discrimination of the Catholic community, and how the black community are living in Chicago. I think there’s real commonalities about how both are, and have, been treated by the police. In Northern Ireland, that’s changed over the past 20 years. And not that I want Chicago to have to wait 20 more years and have many thousands of people’s lives be lost, but I hope that through the conversations that I have I can help people to see the change that can happen and think about the ways that change can come about. But, of course, I’m not a politician and I think it needs to come about from people in powerful places that policing really does need to change.

SJH: Let’s end with a more general question: Why art? Why not something else like petitions or lobbying politicians? Why do art instead?

EF: I think that the arts, in terms of social change, create an indirect way for people to be able to speak and express themselves. So, you can use theatre, spoken word, visual art, contemporary art, dance, movement, to relay your message, but you can also involve the people who need to relay their messages in order to explore the outcomes and solutions in a more intense, deeper way. I think that the arts can attract people who aren’t necessarily activists, but are people who have a story and an opinion. They might just have a casual interest, but I think that there can be really deep political work that happens because of that interest. People take notice of the arts in a very different way.

If you want to help C4AA train and continue to support more groups, artists, and causes like these, please donate. Your contributions really help.