So, for me, I think that the reason that I work in the arts and not so in the charity sector is that we are able to challenge things and question things and push ideas outside of institutions or certain structures. You’ll only get to those places through challenging, through pushing, and thinking outside of how we choose to exist currently.

About Phoebe

Phoebe Davies* is a social practice artist and producer based in London. She often works with mixed-media, including constructed social spaces, video, audio, and print works. Currently, Davies is working on multiple projects including Bedfellows, a sex re-education project working with adults and young people’s groups to explore desire, consent, representation, and feminist porn, while reflecting on and investigating current sex education.

*This interview was conducted in conjunction with the British Council’s Arts and Social Practice fellowship, of which Davies was a fellow in 2016.

Sarah J Halford: Can you tell me a little bit about how you came to your artistic practice?

Phoebe Davies: In my late teens, early twenties, I was studying my BA at Wimbledon College of Arts. That was a fine arts BA in painting. But very early on I stopped making 2D work and started thinking about making time-based work. I come from an education and youth work background, so I’ve always worked as a youth worker alongside my art projects. Following the BA, I was lucky enough to get a traineeship with an organization called Arts Happening and I had the position as Trainee Producer, working across art projects and education and their advisory service that they have for artists. A lot of Arts Happening’s work might be seen as contemporary theatre, where they situate work in public space, as well as working with traditional gallery spaces and theatres. I learned a large amount from them.

We worked very closely thinking about what audiences have access to the arts, and what barriers certain people to be able to access art and others not. I’m from a farming community in South Wales, and so moving and living in an art sector in London, I’m really keen for us to really think about who we’re choosing to make work for, and how that exists outside of maybe the privileged bubbles that definitely exist within art spaces and galleries in particular – what it means to walk into those spaces, or who has the right to walk into those spaces. It’s not always just an open door, I guess.

SJH: And how would you describe your practice now?

PD: So, I work as an artist and I also work as a producer working for other artists, supporting them on their projects. I am currently making a lot of video performance print-based work, and I also make constructed social spaces – which is how I describe them – which will exist where people will maybe read them within an art context as instillations. I make work often with groups of people, so I will do large amounts of research working with groups of people that might have different expertise or skill sets or might be in a certain community or age to unpack ideas that come from that on-site research, which are often social or political.

Because I come from a visual arts background and have lots of experience working in contemporary theatre as well, if we are hosting workshops and thinking about using a gallery space or a museum, often I have a very strong design eye and aesthetic to my work. So, I will think about how we will design that space to open up conversations. Whether that’s making furniture that exists in that space that can be used in many different ways, or we’re making backdrops, fly-posting, making up some tables that have got different references, or showreels within the space. So, I guess thinking about how we make spaces and use those spaces to often share knowledges but within a certain aesthetic that I develop.

Photo by Rowena Gorden

SJH: That’s great. You say that you like to create “constructed social spaces” that often take on a social or political bent – can you share an example of that?

PD: One example of that toured in 2013-2014 with a project called Influences, which was a feminist nail salon that was always developed in conjunction to different women’s groups locally to where it was toured. We designed not only the space as a site for conversation around contemporary gender politics and what was relevant to the groups we were working with, but also it hosted a series of workshops and events and talks – and it was a functioning nail salon. So, it’s not only a space where you come in and cruise around and look at stuff, but more that you’re sat in it, you’re learning in it, you’re hosting conversations in it, and how do we develop design to look at that.

SJH: So how did the feminist nail salon, and the program in general, work?

PD: So, when we work in groups we talk about the fact that we have the platform, if we choose to as a group, to host a space that could open up conversations that are relevant to women and non-binary folk local to the area. We talk about what issues might be relevant that they may want to host conversations about. We run nail salons that depict women or people of influence who are conversation starters around those themes. So, they might be social activists who are fighting to end violence against women. They might be photographers who depict trans communities in townships. Then, we work together to design these nail designs that depict women or people who are doing work that might be socially or politically-relevant work. So, that’s where we start from.

We want to host that space for people to have their nails done and open up further conversation. So, when you enter the space there may be a design at different tables that you can take a seat and get your nails done, and when you sit down there you’ll get a menu of people that you can choose to have applied to your nails. Then, there’s most likely going to be a live reader that we’ve put together. When we were in South Africa, an artist duo called Sober and Lonely brought a fantastic feminist and SciFi library that we were able to host. There may be some audio work that you listen to. The space will also be designed with probably vinyl wraps or fly posters that we’ve designed showing images that we’ve found as a group that depict women working in different ways. You’ll also have information about the women who you’ll have designed on your nails.

So, we spend like two months running workshops, talking about what is relevant for young women and then who could open up those conversations. Also, we think about a demographic of who we’re trying to show, if we’re thinking about it as a set of 10 . Some of those people are local leaders, so you might have a very well-known female activist, like Malala, but you might also have somebody who’s doing really important grassroots work.

Photo courtesy of ArtsAdmin.co.uk

SJH: You conducted this project for a few years, which would suggest that something kept you coming back to it. So, what was it that you kept coming back, or that you thought was working?

PD: That project was in very high demand. Lots of groups were asking for us. So, when you get continuously invited by groups who you think are very interesting – that’s the reason that we kept developing that work.

SJH: Why do you prefer to create interactive art pieces rather than having someone come into a gallery and look at a painting or instillation?

PD: Sometimes I’ll make a piece of work that is to be viewed or read by the audience where there isn’t a conversation that goes past that. Other times, the work will host conversations, so it will be about opening up those conversations. The reason I hope for that to happen is because often it’s a very one-way experience within certain art sectors. And I think that, for me, some of the most interesting moments happen when there’s things that can be discussed or unpacked, not just by yourself when you leave that space, but currently located within the work. Also, I’m really keen to create ways that those conversations can happen across different audiences. So, what it means to have conversations with those you wouldn’t normally have conversations with. And so that’s why I like constructing spaces that allow that to happen.

SJH: Can you tell me about a time when those conversations were able to happen?

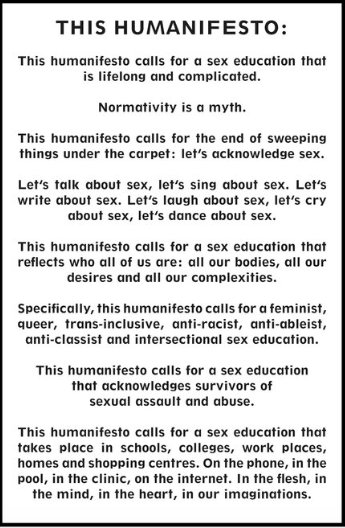

PD: So, an example of that would be a research project that I’m running with two other artists called Jenny Moore and Chloe Cooper, which is called Bedfellows. It takes many different strands of art – like live performance, print, workshops, radio shows – and unpacks how we learn about sex education, which is really a life-long process – we often call it sex re-education. Thinking about how we learn about consent and desire and relationship models.

It’s quite interesting, as well, because realizing how your role as an artist within that, your role or your team’s role of hosting or facilitating is so crucial is something that I’ve definitely learned through working with Jenny and Chloe. When we have an event that we run called Sex Talk Meeting, which is where we create a space made out of about 20 to 30 white duvets and we’re dressed in like, TLC silky pajamas and we have a soundtrack and we perform some dancing at the beginning that is very tongue-in-cheek, and sometimes we offer people drinks as well. We host an evening or afternoon of talking about different issues around sex. Obviously, politically, that can be very emotional, socially, politically, emotionally. I believe that you cannot create safe spaces but you can put things in space to make sure that those people in those spaces are choosing to look after themselves and other people there.

Photo courtesy of the Tate Modern

So, often we talk about the rules of the bed when we’ve made this love bed. Everyone’s invited to come and sit in the bed. We’ve done quite a few of these. We create these booklets, and during the evening we will show three different references, we’ll have some starter questions, and we’ll invite people to talk about these ideas with whomever is sat near them. So, you’re not necessarily talking about it with the people you’ve come with. And because we ask people to mix up in various conversations, people end up having really extended conversation with people who they may have just met that evening.

How we end up advertising these events will very much determine who’s sat in the room. So if it’s a group of local secondary school teachers, we’re trying to figure out how they discuss pornography at school, with the fact that young people access pornography so much freer than maybe they did when they were younger. So, you might get people who are there for the music who’ve come because certain people are playing and they come and take part in a sex talk meeting then.

Our role within that is so important – so how we choose to facilitate those spaces and how we choose to open up those conversations, being aware of how these conversations could be triggering. So, a massive part of this is to understand that we all come with different experiences, and to not pass judgment on other people’s opinions and experiences from that. And it’s quite amazing that you can actually host spaces where people will talk very openly about sexual politics.

SJH: Would you read us some of the starter questions?

PD: Sure. “Can you be queer without being L, G, B, or T?” “Is queerness merely an identity exercise or is it tied to the more tangibly political: like economics, racial injustice, or our relationships to the state?” “Is queerness about who you are or more about what you do?” And my favorite one is: “How can you be sexually free? How do you let go? Do you always have to have the same sex or does the sex you have change with different people? What does it mean to like being penetrated or being the one doing the penetrating?”

Photo courtesy of Phoebe Davies

SJH: Can you tell me about a specific night that went really well and why you thought so?

PD: Actually, the things I think of being most successful are the research groups that we’ve set up. So, we run monthly research groups where we have a rolling email list of people who might be educators, artists, producers, academics, researchers, or care workers, or sex workers, and we invite them in to spend an evening looking at certain texts with us in a really informal way, hosted in our studios. And that has been really important to inform how the work can exist. So, that isn’t the work, but it’s definitely the model that has helped us to unpack the ideas that we’re working on and how we want to push those things forward.

SJH: Can remember witnessing a conversation where you thought the impact was really powerful, even if the responses were difficult ones?

PD: I recently finished working specifically with a school in East London, Mulberry School for Girls, which is a predominately a Muslim girl’s school – 99.97% of the women who attend the school are Bengali Muslim. Those women taught me so much about how we learn about consent and desire. We made a print, which they call a zine, and putting this together really shifted my ideas of also ability for action within schools. The school is taking this as the basis for all of their future sex education from year seven on. They are retraining their staff, they’re getting us in to help us retrain their staff, and they are talking to the students about how they can potentially work with the parents. One of the largest conversations there was the fact that we cannot just have these conversations as women, we need to also push much more broadly within our communities, which not only means men’s groups but also means our parents and the community leaders outside who, often in the UK in particular, parents and communities are very nervous about what’s taught within sex education. All of this is currently being shifted in the next couple of years.

So, the young women I was working with have advocated for the zine that they made to be translated into three different languages because some of their parents do not speak English. So, not only are they saying, “Yeah this is great,” but that it needs to be in these three different dialects. I think around the table we had seven different dialects and were like, if we hit these three, then so many of the parents who would not be able to access this information would be able to. It just kind of blew me away that they suggested such a larger action outside of that.

SJH: And why do you think caused that to be so successful?

PD: It was about working collectively, it was about the fact that there were different opinions in the room – that my opinion was one of seven or eight equally valid opinions in that space.

The other thing is that when we work as me, Jenny, and Chloe, we work as Bedfellows, but we’re three white women in our early 30s. So, we’re really conscious of it’s really important for us to establish that we’re not an authority on any of this. We’ve done a lot of research into it, but we constantly collaborate with other artists. It’s really important to acknowledge a multitude of different histories and stories, not just certain voices.

Photo courtesy of the Tate Modern

SJH: And what about one of the sex talk meetings or workshops that didn’t go so well?

PD: That one, actually – we were invited to come and do a sex talk and it was the first time we’d actually done one. And what we wanted was about 50 people, and we wanted to make sure that everybody who’s working on it had been briefed before and everybody knew how we would work as a team to safeguard that area, and how we can make sure that, where possible, we’re making a space that people felt comfortable in. And we had 500 people turn up. This was in the galleries in the Tate that is really, really big. So when you plan to do something that you hope is going to be quite intimate, and then you have 500 people, you have to totally change the way you’re going to host those conversations with that work.

So, for me it was a huge learning curve because so much of it actually failed. Well, not failed, there were people who really got into the conversations and really benefited from what we were doing, but at the same time we maybe couldn’t give it as much time as we wanted to because we were hosting this very large group of people who all wanted to talk about different sexual experiences.

Photo courtesy of Phoebe Davies

SJH: It sounds like there have been some interesting conversations generated from your projects, but what happens after the initial conversation is over? What next?

PD: I think that the kind of projects that I’m involved with push toward long-term change. If you think about me working at Mulberry School for Girls, you can see very quickly an outcome: institutional change, the retraining of all of their staff. The whole of the senior leadership team having a conversation around queer desire. Offering sex ed, from year seven, all the way to being trans inclusive and intersex inclusive. These are things that are happening. Specifically, in the Bedfellows program, within work that’s maybe the video work that I do, the print work that I do, that you might see and then leave from it, it’s not so obvious where that sits. It also, to me, I don’t want it to be that obvious. I want it to slowly choose to challenge or question the perceptions you might have on how people choose to situate themselves within society.

So, for me, I think that the reason that I work in the arts and not so in the charity sector is that we are able to challenge things and question things and push ideas outside of institutions or certain structures. You’ll only get to those places through challenging, through pushing, and thinking outside of how we choose to exist currently. A lot of the choices that we’re making are influenced by the fact that we exist within a patriarchal, racist society, and the only way that we can dream of spaces that are outside of that is to be experimental and to be imaginative and to think about alternative ways, and one of the ways that I choose to do that is as an artist.

You must be logged in to post a comment.