From the mid 1950s to the early 1970s the Civil Rights movement involved tens of thousand of people and changed the civil rights for millions. It was also a consciously creative campaign.

Artistic Activism is not new. All effective activism contains creativity, uses culture. and employs artistic techniques. And from the activists and organizers that came before us we can learn principles of creative activism that we can use today.

Here are some lessons that we can learn from the US Civil Rights and Black Power Movements.

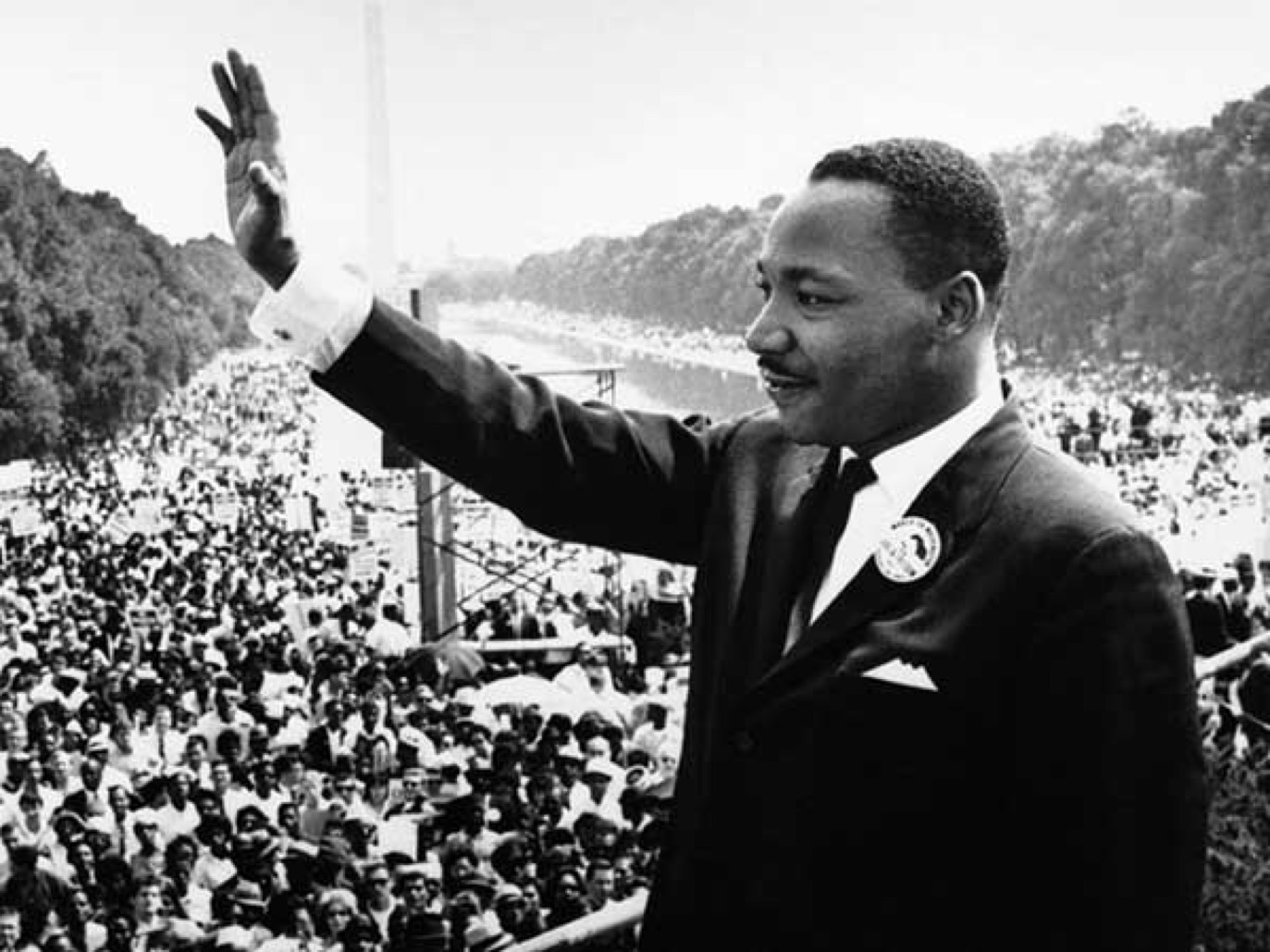

This is how we often remember the Civil Rights Movement: The masses of people led by the shining star of courage and righteousness the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King was a brave and righteous individual, no doubt, but his – and the movement’s – power and efficacy was communal and cultural.

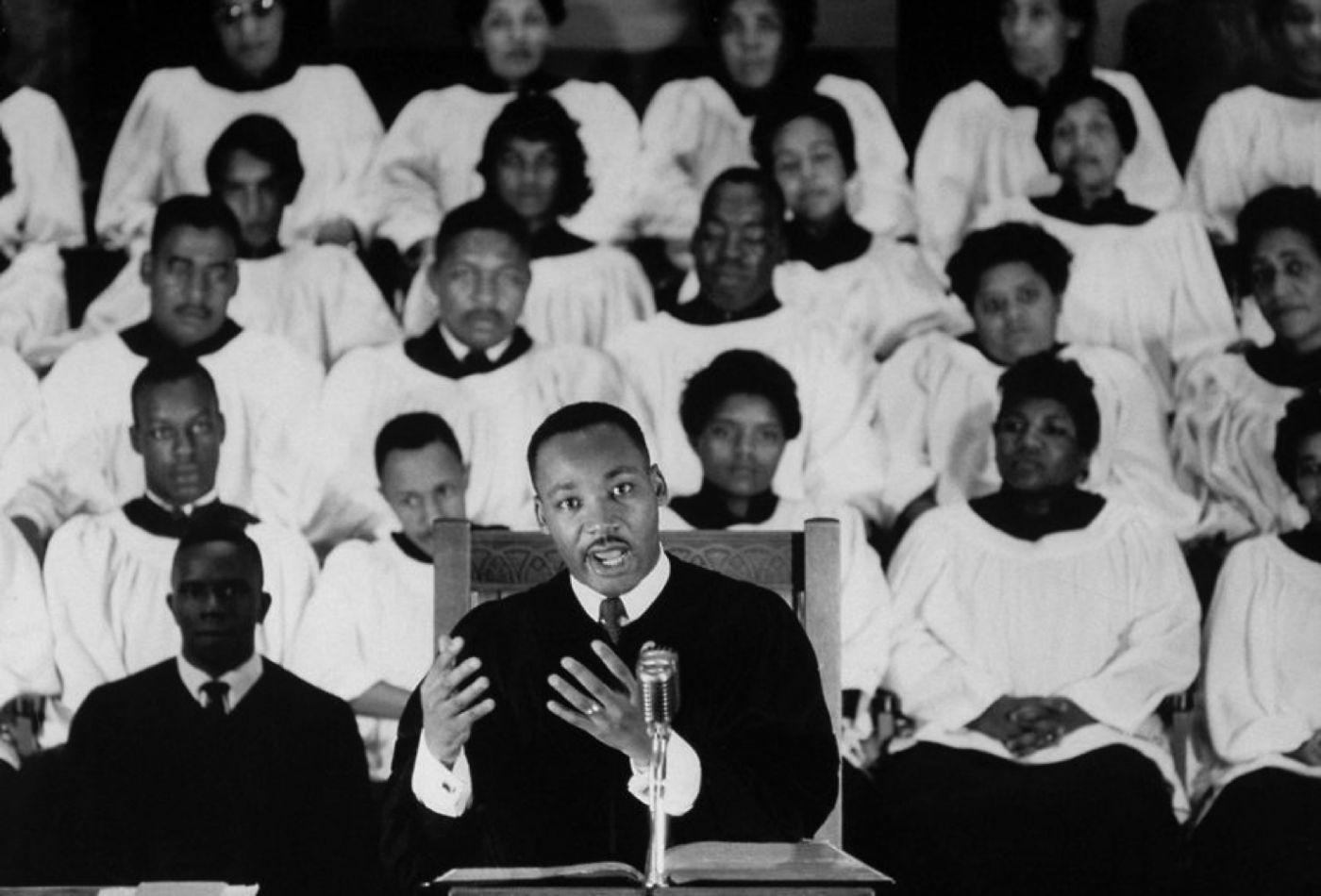

But the Civil Rights Movement would have been inconceivable without black churches. Not just their institutional role: being important institutions that could offer organization and leadership for the movement. But their cultural one: songs that served as the sound track to the Civil Rights movement, and the communal experience solidarity in singing. Creative material — images and narratives — to imagine a struggle against great odds and the possibility of arriving at a promised land. The story of Moses and slaves fleeing from bondage to the promised land. And a stage to collectively perform these acts of creation and imagination. Every week, church provided a stage where a different society, one not controlled by white supremacists, was enacted. The lesson?

Lesson: Build from foundations

Activists never start at ground zero, and it’s a mistake to think that we create something from nothing. We are always drawing from the repository of meanings and images and words that already exist.

This is what makes changing society so hard: we are stuck within the very culture we are trying to change.

But even within the most oppressive of societies there are pockets of counter-cultures: repositories of resistance that provide a cultural foundation: the stories, the songs, the cultural institutions — upon which we can build.

Here’s an epic moment in the Civil Rights struggle: Rosa Parks, a Montgomery, Alabama seamstress, tired after a long day of work, who in 1955 refused to give up her seat to a white person and sit in the back of a segregated bus. An act that launched the modern Civil Rights Movement.

At least that’s what we are taught. Here’s the real story: Rosa Parks was not just some innocent who happened to be in the right (or wrong) place at the right (or wrong) time. She was an experienced activist and political organizer, she organized around defending the Scottsboro boys in the 1930s, hosted “Voter League” meetings in the 1940s, became the secretary of the local chapter of the NAACP and trained at the Highlander Center, a progressive politics and cultural training center in TN. She later moved to Detroit where she protested against the Vietnam War, was a supporter of Black Power and fan of Malcolm X. Rosa Parks refused to move knowing full well what she was doing and what the ramifications would be.

When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in Montgomery Alabama in 1955, she was tired and she could not sit in the front of the bus in the segregated South. But her act was a performance to dramatize the reality of racial inequality to a larger world that either didn’t know or didn’t care.

In fact, this iconic image was taken more than a year later, on Dec. 21, 1956, the day after the United States Supreme Court ruled Montgomery’s segregated bus system illegal. The man sitting behind her in this famous (here un-cropped) photo is not the Southern bigot who asked her to move, as one could easily assumed, but a United Press reporter asked to sit there for a staged photo well after the fact.

Lesson: Perform Reality

We often think of performance as creating a fantasy. It can be this, and this can be useful as it allows us to visualize and act out our dreams. But performance is also useful in dramatizing reality. The truth is important, but the truth needs help.

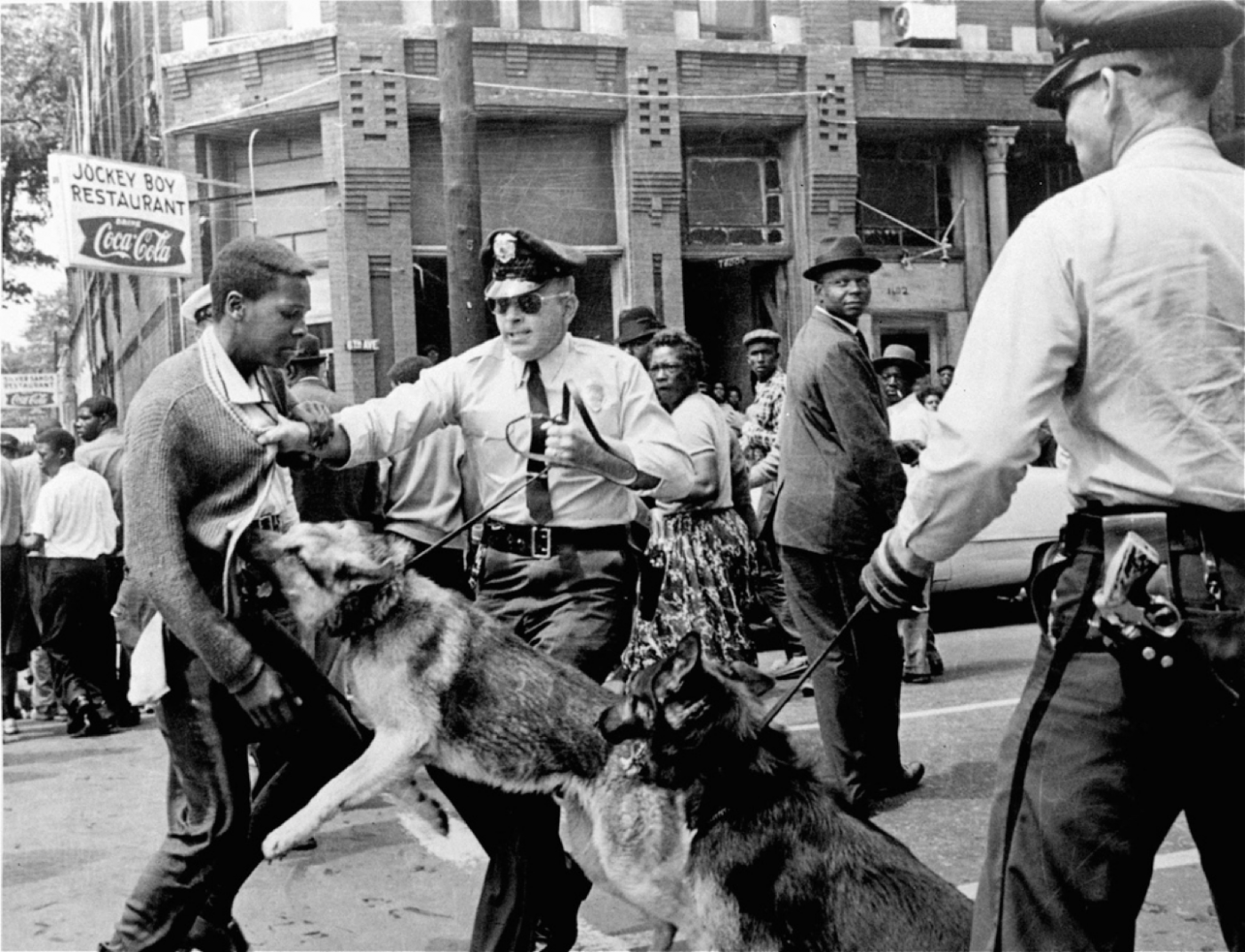

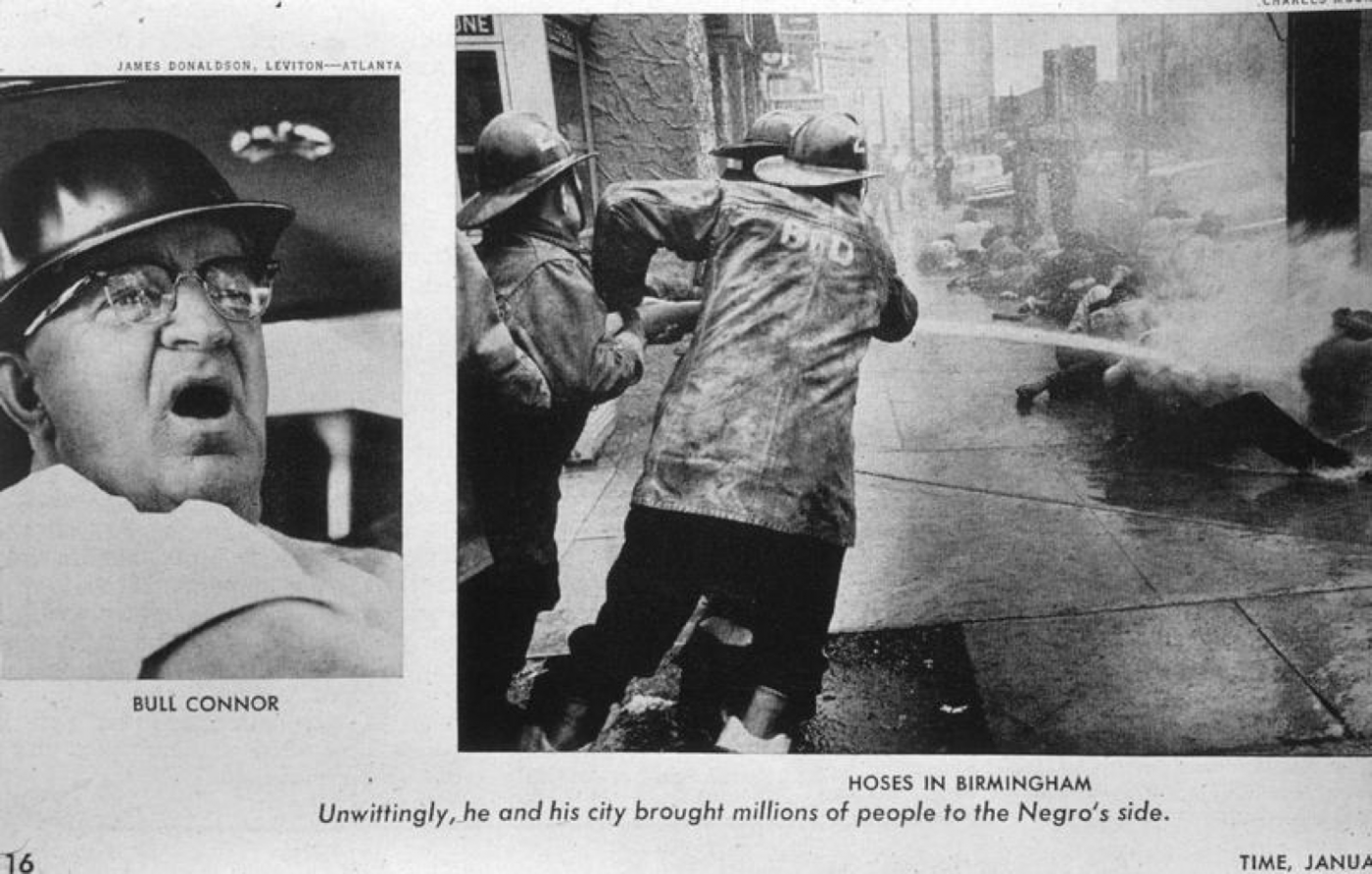

Nowhere was the Civil Rights Movement’s “performance of reality” is better demonstrated than the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) campaign to desegregate Birmingham Alabama in 1963. So many of our images of the brutality of the Southern racism and the Civil Rights Movement come from that demonstration: Men being attacked by police dogs…

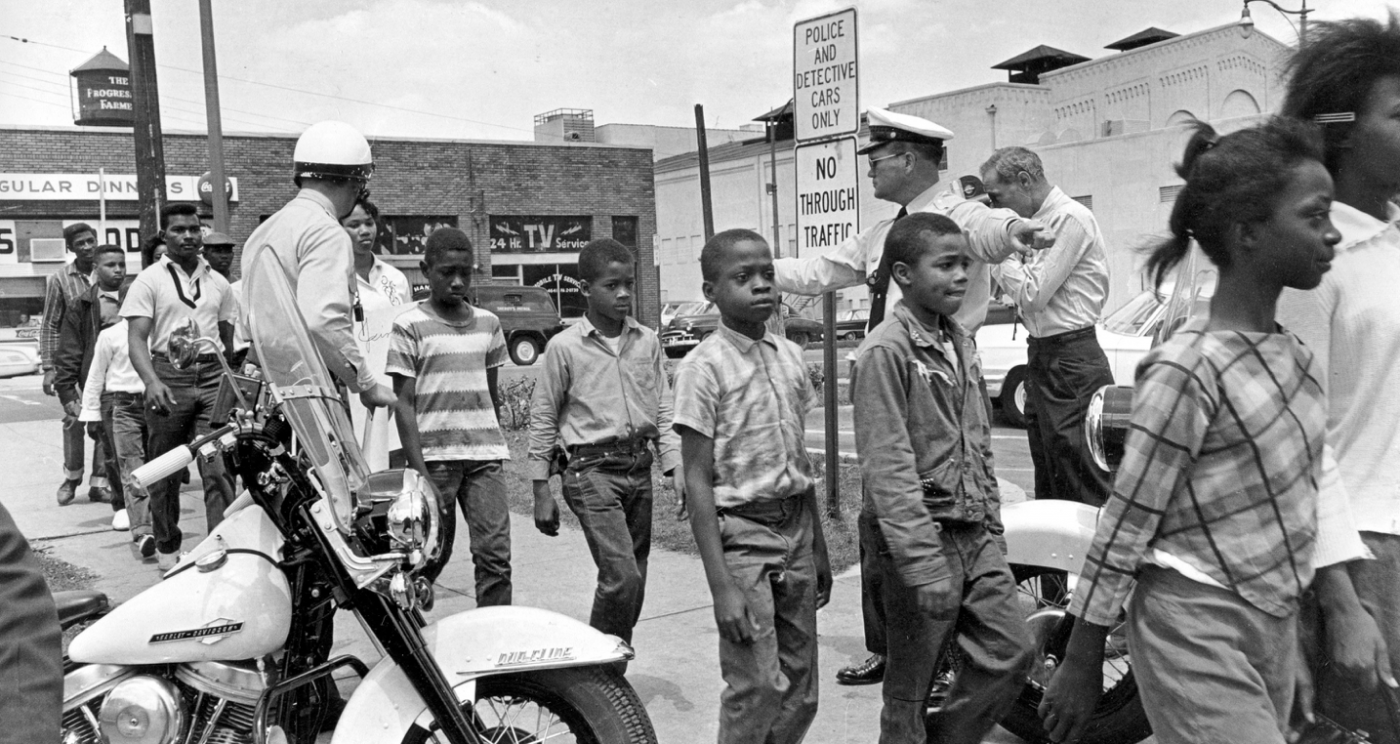

School children being marched off to jail as part of the Children’s Crusade.

Protestors assaulted by fire hoses.

Everyone knows these pictures. What’s less well known is that the campaign to desegregate Birmingham Alabama was also staged, in fact it was staged twice. A year earlier, a similar protest had been attempted in Albany, Georgia: and it failed. It failed in part because the police simply, and peaceably, arrested everyone and distributed them in jails around Georgia.

The SCLC learned. They picked Birmingham because it had a long history of labor organizing, because of a recent spate of church bombings, but also because of Bull Connor – the acting police chief – a former Klansman who was known for his belligerent racism. The SCLC cast Connor in the role of villain and he played it perfectly. The result was the images we know now: images of black decency and courage, facing down white violence and racism. Broadcast around the world. It was a brilliant – and creative – act of “strategic dramaturgy” as social movement historian Doug McAdam has called it.

Lesson: Make the Invisible Visible

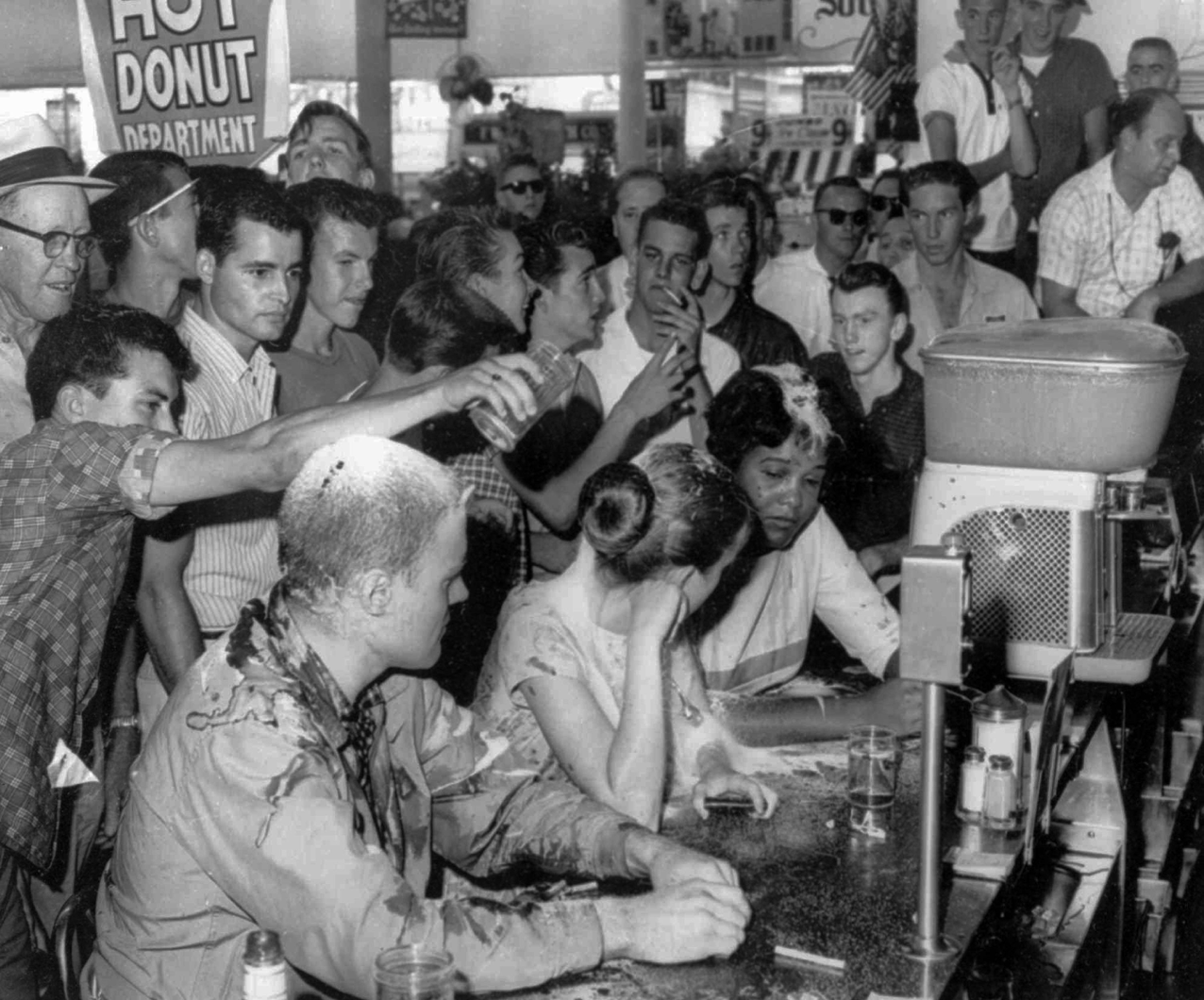

Again, to say these events were staged with an astute eye for aesthetics does not mean that they were fabrications. In the 1950s and 1960s African Americans in the South were not allowed to sit in the front of the bus, eat at segregated lunch counters, or protest in the streets. In the 1950s and 1960s African Americans who stepped out of line were arrested, beaten and brutalized. The activists of the Civil Rights movement were not fabricating fantasies, they were dramatizing reality – a reality invisible to most of the US and the world.

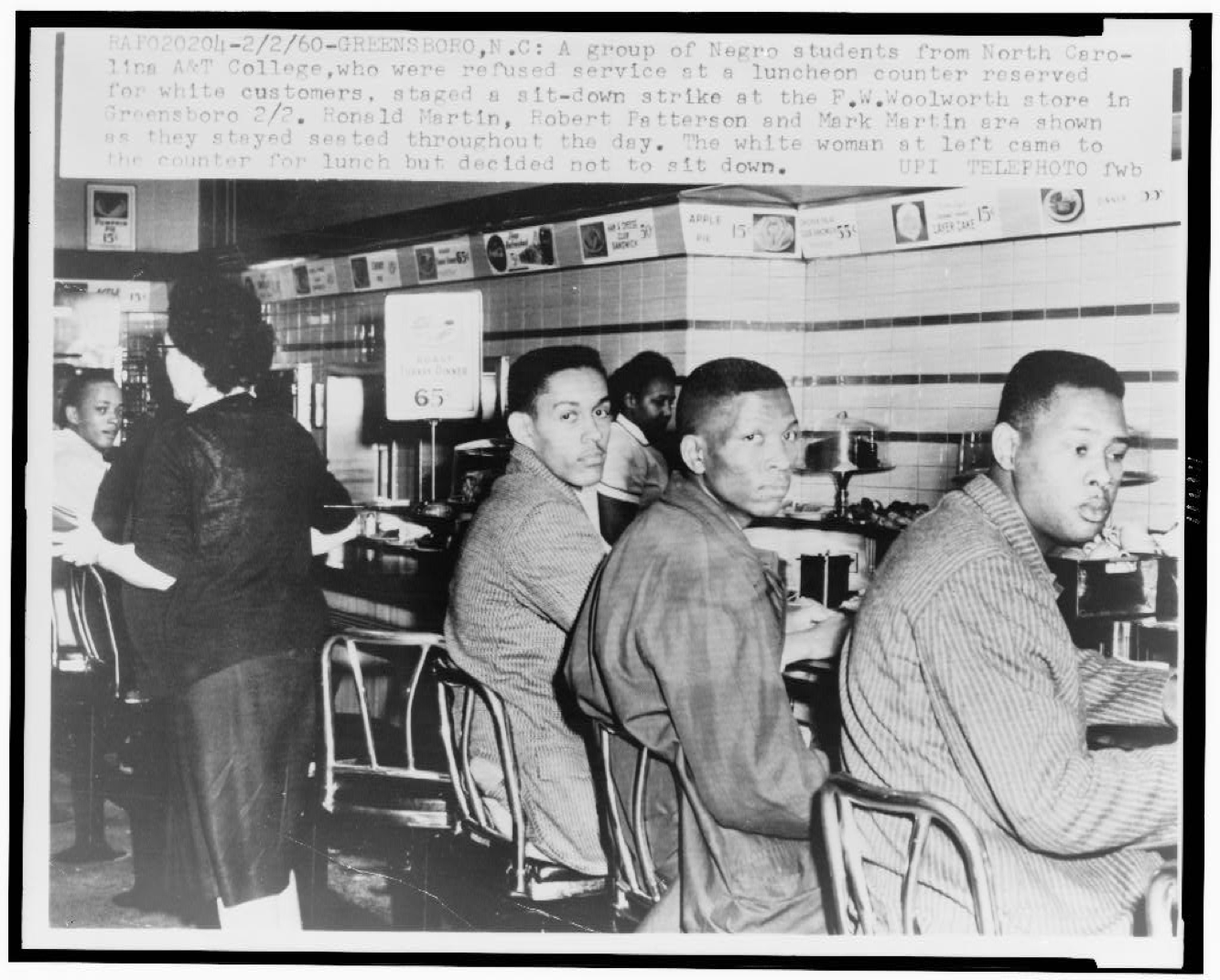

Lunch Counter Sit-Ins were a major creative tactic of the Civil Rights Movement. One of the most famous was by Students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University at the Woolworth’s in Greensboro North Carolina in 1960.

The Activists were assaulted and humiliated… but they were ready for this.

Before the sit-ins the activists trained for what they would encounter because they knew that how the protest would be remembered depended upon how they acted.

Lesson: PROTEST AS PERFORMANCE

And old friend and talented artistic activist, David Solnit, once told us “All protest is theater. The problem is that most of it is just bad theater.”

So consider how to make your protest a better performance.

- Practice blocking

- Know your lines

- Consider lines of site

- Create a tableau.

- Consider your entrance and exit.

Think of protest as a dramatic performance.

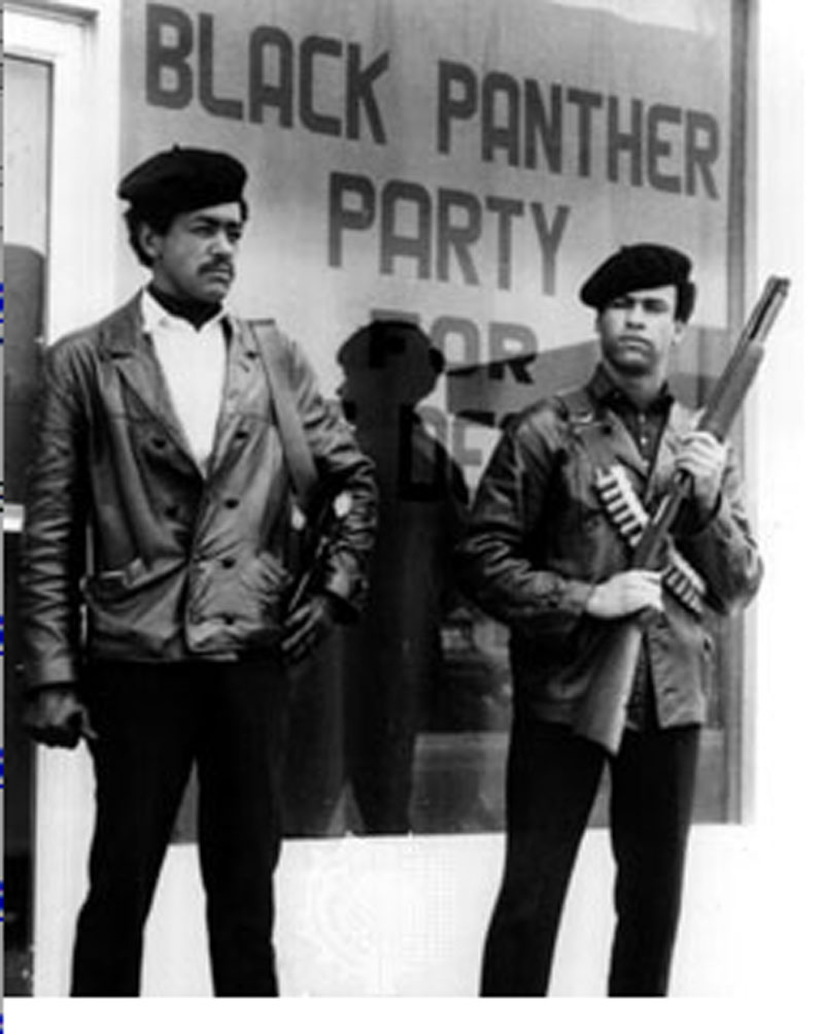

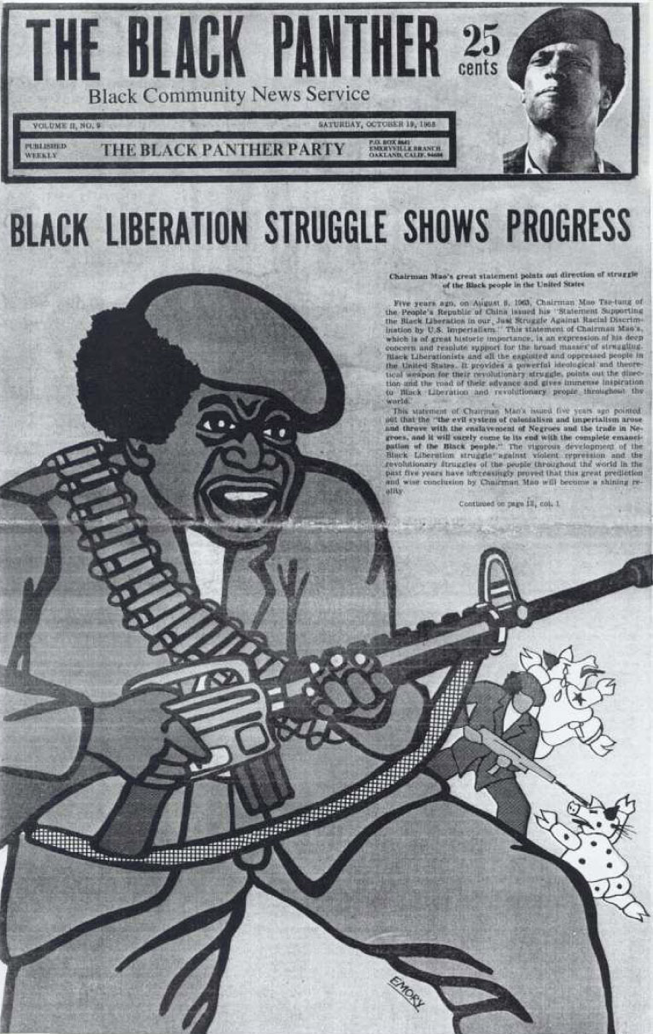

The Civil Rights Movement trained a generation of activists about the power of the image and the performance, and the idea that aesthetic creativity was an integral part of protest politics. These lessons were passed on — most immediately to the Black Power movement and groups like the Black Panther Party.

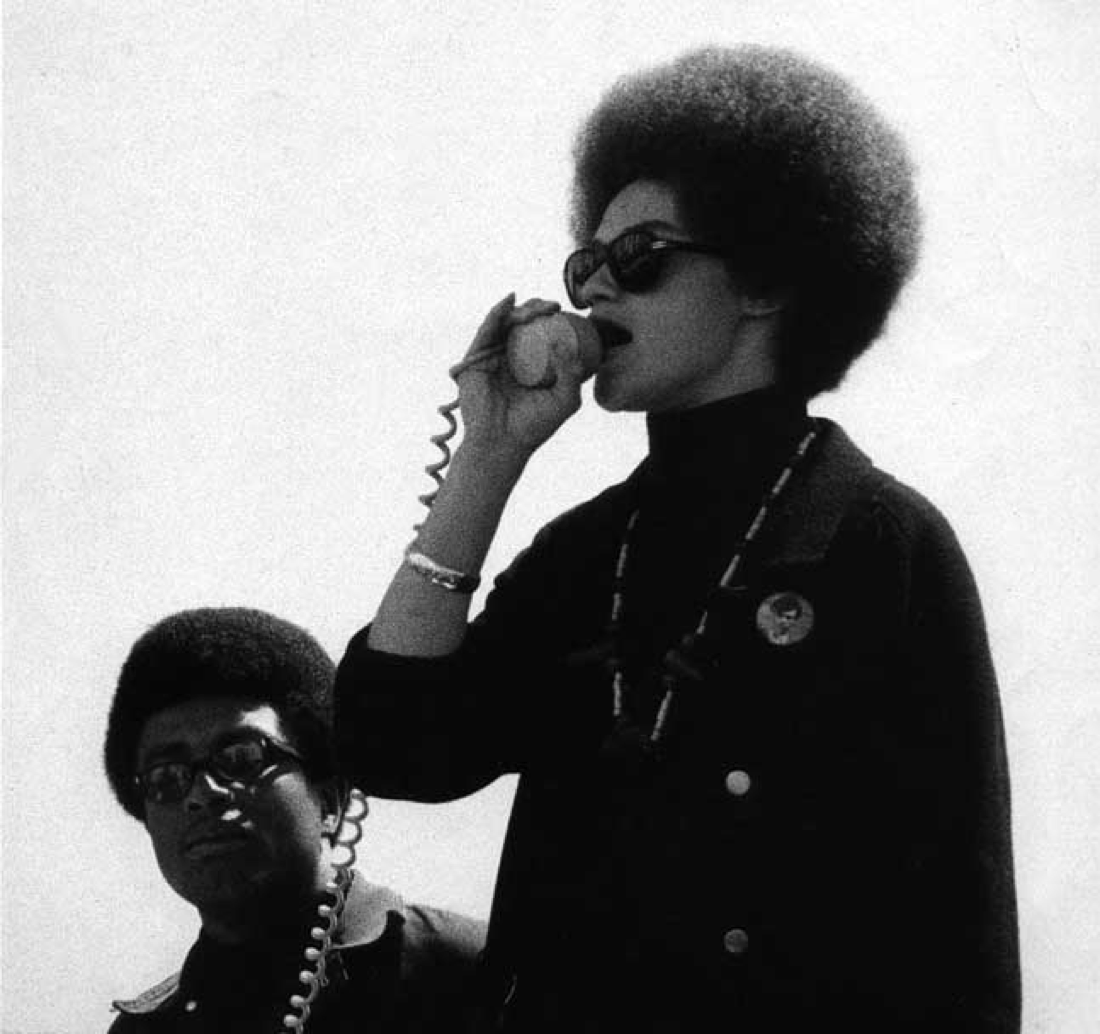

The Black Panthers formed in 1965 in response to northern police violence against African-Americans. Distancing themselves from the suits and ties of the Civil Rights Movement, they dressed and acted the part of militant revolutionaries

Wearing Berets, black leather and, where they could, guns.

Quite simply: they were baddest, coolest, hippest looking people around.

Lesson: STYLE MATTERS

We, as activists, are part of the art of activism. How we, appear matters: it communicates a message as powerful as the words on the pamphlet you hand to someone. People associate the message with the messenger. Perhaps more important: People associate the very idea of activism and being an activist with how we present ourselves. This is why early civil rights activists dressed in coats and ties and the Black Panthers wore leather and berets: both communicate the message, to different audiences and in different contexts: this is what an activist looks like. But it’s not just about clothes, it’s the attitude you wear.

Militant message and style resonated with younger activists and it spread from the African American community to others: Chicano Brown Berets, Puerto Rican Young Lords, and the American Indian Movement (AIM). All these groups were were masters at staging dramatic actions, and one of the most brilliant was AIM occupying the former prison on Alcatraz Island off San Francisco in 1969 and declaring it a new Indian Reservation.

We, the native Americans, re-claim the land known as Alcatraz Island in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery.

We wish to be fair and honorable in our dealings with the Caucasian inhabitants of this land, and hereby offer the following treaty: We will purchase said Alcatraz Island for twenty-four dollars ($24) in glass beads and red cloth, a precedent set by the white man’s purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago. We know that $24 in trade goods for these 16 acres is more than was paid when Manhattan Island was sold, but we know that land values have risen over the years.

They then issued and publicized a humorous “proclamation” to explain their action to the public:

We feel that this so-called Alcatraz Island is more than suitable for an Indian Reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards. By this we mean that this place resembles most Indian reservations, in that:

1. It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

2. It has no fresh running water.

3. It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

4. There are no oil or mineral rights.

5. There is no industry so unemployment is great.

6. There are no health care facilities.

7. The soil is rocky and non-productive; and the land does not support game.

8. There are no educational facilities.

9. The population has always exceeded the land base.

10. The population has always been held as prisoners and kept dependent upon others

LESSON: BE SERIOUSLY FUNNY

Indigenous Peoples have few reasons to laugh at their plight. But these AIM activists understood that humor is a key element in successful creative activism. Through humor you can reach people who would otherwise shut you out; through humor you can bring up “serious” issues in a way that doesn’t threaten your audience.

But humor is also important for activism in another way: it builds bridges. It takes two for a joke to work. This is something painfully aware to any stand-up comic. But when a joke does work it builds a bond between the person making the joke and the person laughing. They share the message and an understanding (even if they don’t agree).

But most often the image projected was not one of humor but of militancy: the berets, the clothes, the guns. This uniform was a potent symbol of black, brown and red power to young people of color who were impatient with and saw the limits of the legal reforms of the Civil Rights movement.

The Black Panther Party did a whole lot more that stand around looking like revolutionaries. For example, they created programs to directly help people in their communities like their free food and free clothing program, and best known: Free Breakfast for School Children program started in Oakland in 1969 that then spread across the US.

But the militant style and rhetoric projected by the young activists gave the police and the FBI the justification they needed to harass, arrest, and murder members of the Black Panther Party, AIM and many others. For instance, in 1969 the former NAACP and current Black Panther organizer Fred Hampton was assassinated by the Chicago police while he was still in bed. The symbol of militancy had a double edge.

LESSON: SYMBOLS ARE SLIPPERY

The lesson here is a serious one: Symbols and messages can be interpreted differently by different audiences. And our opponents can consciously manipulate our symbols for their ends. Always assume they will.

But the original, inspiring symbol of the Black Panther still perseveres and still mobilizes.

Thank you for reading. We include this as part of the history of artistic activism in our trainings on the history of artistic activism. Please feel free to share, with attribution, as all our work is Creative Commons licensed.