I think that art is the language of possibility. Art is the language of the future, and through art we can actually create the vision of the world we want to see…To document how you’re experiencing life in a way that may not be scientific or is more about myth-making and storytelling, that to me is art. Art is about myth-making.

Favianna Rodriguez is a transnational interdisciplinary artist, cultural organizer, and Executive Director of CultureStrike, an artist collective that uses cultural work as the central tool of their activism. In addition to her work at CultureStrike, Rodriguez is a prolific artist and created “Migration is Beautiful,” an image that has been widely adopted as a symbol of the migrant rights movement. She lectures globally on the power of art, cultural organizing, and technology to inspire social change, and leads art workshops at schools around the country.

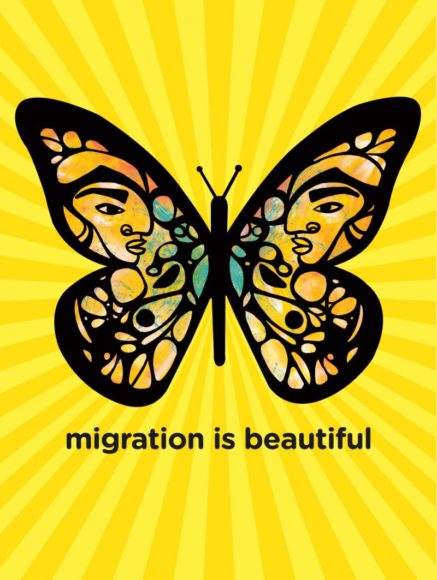

Stephen Duncombe: I wanted to ask you about the “Migration is Beautiful” monarch butterfly. You know it’s one of my all-time favorite sort of symbols, campaigns, so on and so forth. Do you mind telling me where the idea for the monarch butterfly came from, what you did with it, and how you thought about the whole?

Favianna Rodriguez: The concept of connecting the monarch butterfly to migration is something that I believe has been going on since the 80’s. People use that metaphor, because the other sort of metaphor that exists, especially for Day of the Dead, is that the monarchs carry the spirits of the dead. So, I think in general it’s a metaphor that’s been out there. What I did differently and how I was able to really maximize it, is I created a symbol that explicitly connected the migration of insects to the migration of people, and that it was actually something that it was dictated by nature.

So, because there a lot of times the butterfly had been used like an add-on element to a message that would either be “stop deportation” or “migrants are human beings” or “migrant rights are human rights.” Still framing it through the lens of human rights or criminalization. And what I wanted to do is frame it through the lens of nature, and not acknowledge or give importance to the border and the wall, because it’s a man made concept, versus that it’s a nature concept. And the other things is that I wanted to sort of speak from a place of being affirmative and visionary and even futuristic, or naturalistic, using nature as a way to story-tell.

Because I feel that often a lot of our messaging is a fighting message. It’s a message about what we’re against. And so often our messages are about what’s politically feasible. And so, when I created Migration Is Beautiful, it was about making a statement that we are a part of nature; we migrate. As human beings, we’ve always been migrating since the beginning of time.

So, that’s something that I did differently that I actually think led to the mass appeal of it, because it was a very open invitation and it was an affirmative message, it was a positive message. The image is not just the monarch, it actually has two faces in it, which added to this sort of blending of humans and the natural world.

And then I created merchandise with it, and I created things that people could put up in their living rooms, t-shirts, earrings, because I also think that so often a lot of things just live online, but I do think that people really want to show their values. It’s important that we create objects that people can attach themselves to. I also created make-your-own butterfly kits. I created an exercise with my organization, CultureStrike, where we had videos on how you can cut out your own wings. Because even though it sounds easy, it’s actually not easy. To make your own wings that’ll stay on and doing it with just like DIY in your home, it actually is a few steps, so it required a whole curriculum. It was around: How do we make this image? But then: How do we also facilitate its distribution and its use.

SD: You facilitated using your skills in order to make it look nicer, make it more accessible to people. Was that a conscious decision? Like: My role as an artist is to work with a movement and do this sort of work?

FR: Yes, I also think that I wanted for people to have fun with it. I’m an artist, and I know that making art is a big part of what I want to achieve. It’s not just about regurgitating a message, it’s actually the activity and the action of making art and community is in itself healing. I always want to create opportunities for people to engage with the work in a way where they’re also embodying it. And having fun, not just attending a protest, but actually putting on a costume that is fun — migrant kids especially, because I would do butterfly making workshops with a lot of immigrant kids. That they kind of have some pride in creating it, but also that it’s a fun and memorable experience.

So, I did that because I feel that our movement does not do that well. Our movement, overwhelmingly pain-oriented, and a lot of the ways that we activate are not around comedy, they’re not around joy. And they’re not necessarily around nature culture. My organization’s contribution was thinking of ways that people can engage with the subject. And not just the people who are already engaging in it, but teachers just regular folks who are looking for an activity for their kids or for teenagers. And I found it to be super effective.

I’ve done tons of those workshops, and wherever I go the old ladies, the moms, the kids, they come and they’re just painting their butterflies, so immersed in it. Which tells me that we actually also need to prioritize art making in our communities, because that’s also a way to heal.

“Migration is Beautiful” by Favianna Rodriguez

SD: Can you talk a little bit about that, this sort of relationship between art making and politics making, citizen making, wellness making?

FR: Yes, so, to me art is about having a voice and it’s about expressing yourself, which is a fundamental right. And it’s also about creating something to note and to reflect your existence. So, as a woman of color I make art because I don’t see my existence reflected back to me in mainstream culture, I see whiteness reflected back to me. And I want to create the stories and the images that I long for.

I also don’t believe art is neutral. I believe all art is coming from a point of view, and we’ve grown up in a world where overwhelmingly we are seeing the world through the perspective of white men and we’re seeing their art and their gain. And so because of that, I believe that art is a way for people to express themselves through the making of objects or the making of images that allows them the simple their lived experiences in an artistic medium.

A lot of times I’m doing workshops, like political poster workshops, where everyone gets to make their poster. And what I find is that doing something that reflects their values or their lived experience. I’ve also taught art workshops, where I know that a lot of the kids who won’t go to math class will go to art class. So I always have believed in the compelling nature of being able to create things that are a reflection of you, because that’s what we long for as human beings. And in reality, the opportunities to do that in communities of color, are extremely limited, very, very limited. We have a lack of cultural centers, we have a lack of arts being taught in schools where communities of color live. So I think that the creation of art simply as a gesture of contemplation and also the activities that people get to do, is also part of it.

For me, the butterfly also represents transformation. I mean there’s just a lot of ways for it to be interpreted. So, at CultureStrike we believe in it so much that any time we have any kind of collaboration with an organization, we basically do a pop up studio thing. Even in how were designing things, and how we’re meeting and how we’re discussing, everything is done through the modalities of artistic practice.

SD: Nice, that’s great. In a way, you’re answering the question that I wanted to move to next, which is: How do you think social change happens? And what does art have to do with it?

FR: I think that art is the language of possibility. Art is the language of the future, and through art we can actually create the vision of the world we want to see. Human beings have always expressed themselves through two key things: They’ve attempted to understand the world through science and through art. It’s like a very, very old practice. Whether it’s people writing on the walls or the invention of the printing press, the desire to distribute knowledge and a point of view has . To document how you’re experiencing life in a way that may not be scientific or is more about myth-making and storytelling, that to me is art. Art is about myth-making.

And I think that in the social justice world, we have overwhelmingly concentrated our efforts on policy change. And I think that’s a huge mistake, because cultural change precedes political change. And culture has to change before policy does, in fact policy is like the final manifestation of an idea. But what matters is the idea. So much of what we’re fighting is actually ideological. In order to win, we need to have a vision of where we’re going. And that is what art is to me. I mean art is really our imagination. Art is the space of ideas and myth-making and culture-making — it’s a component of social justice, that social justice will only happen when you have activation in the political space, in the cultural space, and in the economic space.

SD: You said something really interesting which is this notion that policy won’t happen unless the culture changes, right? Because policy is a manifestation of culture. Can you explain that a bit?

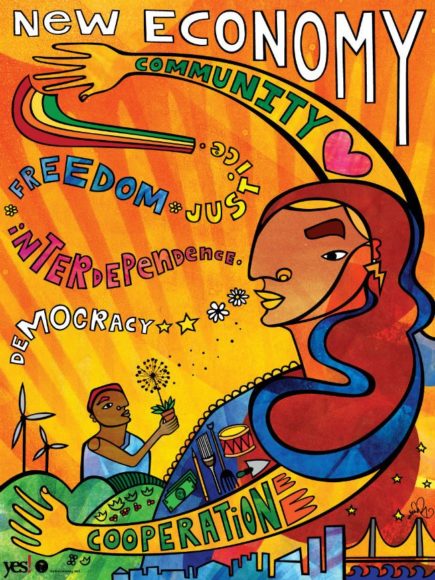

FR: Yes, culture is a set of behaviors and ideas and beliefs. And those beliefs first have to change before someone is willing to vote on it. So, for example, people are not gonna vote for clean energy if they don’t believe that oil is dirty. They have to first believe that oil is bad and solar is good and therefore they’ll vote for clean energy. But a lot of times, the fossil fuel industry has told us that we need oil, oil is a sign of progress. They’ve created a narrative. They’ve created a culture. And we actually have molded our lives around that idea. In order for people to transition off of oil, they first have to be able to imagine what their life can be like — they have to almost unlearn some things.

In order to shift that, people need to see it — they actually need to see it. They need to feel it. But it has to speak to their emotional heart. It’s not just rational knowledge, its emotional knowledge. And art is really well suited for that.

Artwork by Favianna Rodriguez

SD: One of the things I’m interested in is: how do people like you know that what you’ve done works? And how do you know when it doesn’t work? I mean you’ve done a lot of successful projects right? And how do you know when they are successful?

FR: Well, I deal with funders all the time and they always ask me this, but I look at it in a few different ways. First, I look at what the impact on the people who experienced the art was. Like, did they have fun, did they learn a new skill, did they see something they hadn’t seen before, were they moved by the art, did they get excited by it? What was the quality of the interaction with the work or the experience? Because sometimes we also host, it’s not just the creation of an object, it’s a show or it’s a film. So that’s one thing.

The second thing is: Do movement people now have another tool in their tool box that they can leverage? Are they able to tell stories differently? What changes for them? What do they notice that is different for them? I, frankly, believe that they get a different sort of way to be able to talk about the work they do.

And the third thing I look at is, artistically, what was the experience for the artist? So, for example, we just took a big group of artists to the border to have them see the new wall that was built. They were extremely moved, and they were also shocked. They never seen this wall, and they realized that it’s such a fabrication. It’s a straight up fabrication that we need more money for the wall. And that it’s a highly militarized zone, and they were able to see it and experience it. So as a result, those artists now are gonna be lifelong immigration activists, because they have witnessed it, they’re mad, they’re sad, but they also know the truth. I just say, “Just take it in, and you are a storyteller, and try to think about how you want it to come out and the story that you tell.”

SD: And from that experience they have, you have faith that there will be some fruit in the future?

FR: There’s always fruit, and that’s the thing that, I trust artists. We always support emerging artists. We invest so much in the leadership development of grassroots organizers, we need to be supporting the leadership of artists early on, early, early on. And that’s what we do.

So, by the time some of these artists are ready to engage they have a solid foundation of an understanding of the issues, but they also have the ability not to just regurgitate movement messaging. Communications messaging is different than what we need in order to win hearts. Communications messaging is usually designed to get your senator to do X, Y, Z. It’s not designed to move people. So, I mean it’s not designed to move people in the same way where art I about bigger ideas, it’s about a bigger narrative, it’s not just about reacting to the current political reality.

SD: Right, right, it goes back to that sort of emotional knowledge as opposed to just information.

FR: Right. And it’s also more systemic. You know, like when I do projects on factory farming and on fossil fuels, like I really try to think about: What perspectives am I sharing here? I’m not just gonna say, “go vegan,” or I’m not just gonna say “oh, the factory farming industry is horrible,” I’m actually thinking: “I’m gonna tell the story of this little pig. This little pig who was saved, and he’s in a sanctuary now.” Or I’m gonna tell the story of a kid who has asthma because the refineries are in his town. That to me is what needs to happen more.

So, I do believe that as artists we do need autonomy to do our wild crazy ideas. Because again, we’re approaching things from a different . We’re trying to activate culture which is different than activating legislative or policy change.

SD: Sure. Although it also sounds like in thinking about an artist’s autonomy, you also hold artists, or at least hold yourself, up to pretty high standards.

FR: Absolutely. I mean, we have to understand the issues. We’re not gonna be able to be effective artists if we don’t submerge ourselves in the realities. This is also why we need artists with first-hand, lived experience. So we also need the artists who don’t have the experience to actually go to the impacted places and see for themselves, but also listen to local people. Listen to local artists.

Pictured: CultureStrike at the People’s Climate March in 2014

SD: Have you ever had a project that didn’t work? And how did you know that it didn’t work?

FR: Yes, I have had a project that didn’t work. And I knew it didn’t work because it wasn’t shared. The timing of it wasn’t right. you have a good project, if some of these issues are not in the news cycle it might get picked up by some random art people but it doesn’t really move in the way that it needs to move. So I’ve had projects where the timing hasn’t been right or I’m just not tapping into the moment.

SD: And how do you know that?

FR: I follow the news, I follow social media, I see what people are talking about. I just, I’m participating in culture. I mean, I care about culture, I care about pop culture. For example, right now we’re in a #MeToo wave. And that, to me, means that this is the time to talk about a bunch of stories around sexual abuse — it’s a completely different landscape than last year. Or when the fires happened, I’m like, “Okay let’s talk about climate policy.” Now that the migrant caravan is happening, I am pushing out the butterfly again.

Many artists are not always thinking about timing. It’s like they’re spectators, they’re not participants. Like they’re not necessarily participating in the sort of dialogue that’s happening around them. So much of my time is actually understanding what solutions are being proposed. Like, what are we really talking about here? What is the narrative? What are people saying, and where is there some friction? Where are there some openings? And frankly, you could only understand that if you are watching it or if you’re engaging in it. Once you learn the sort of ebbs and flows of it, it allows you to go it at the right time, and to actually ride that wave.

You must be logged in to post a comment.