I think it’s about creating a situation where we do art with political discourse inside an economical-political structure that is in itself transformative. So it’s not so much what we talk about or how we talk about it, but where we talk about it. The context of the production is important.

Fernando García-Dory’s work engages with the relationship between culture and nature in the 21st century, as manifested in multiple contexts: from landscape and the rural, to desires and expectations concerned with identity, to global crises, utopia, and the potential for social change. He studied Fine Arts and Rural Sociology, and is now preparing his PhD on Agroecology. His work addresses connections and cooperation, from microorganisms to social systems, and uses traditional art languages, such as drawing, in his collaborative agroecological projects, actions, and cooperatives.

Emily Bellor: So Fernando, to begin, could you tell me a little bit about your practice and how you came to it?

Fernando Garcia-Dory: Well, in general I would say I don’t actually define my practice as art and activism.

EB: Really, how you would you define it then?

FGD: I would say that I did define my practice as activist for a couple of years when I was younger, around eighteen years old, but then I realized that activism wasn’t the form of political action I wanted to develop. I believe more in creating ways of living than activities, that’s why I became involved in cooperative farming and economies. So I started developing my art practice and developing collaboratives of social practices with people, with political critiques of the status quo to promote social change. But I wouldn’t say that necessarily connects with activism.

For example, I started a project called European Shepherds Network, which connects shepherds from different countries with each other. That was presented at Documenta 12 in Kassel as a kind of performance: the shepherds were meeting in the future and talking about the events that had produced social change in Europe. I try to think about bringing the political question of art, and try to be goal-oriented. So, I try to be effective and make useful projects. But I think there is some difficulty and bringing art and activism together.

EB: Why do you think there’s difficulty there?

FGD: Because, as I said when I received the Creative Time prize, there are different elements, like the possibility of engagement in a question, and dissolving oneself in a collective, that are contradictory with how the art system works. So I said that maybe a good activist makes a bad artist, and a bad activist could make a good artist. The art system recognizes artists who legitimize themselves through self-promotion—because it’s based on the notions of career and success—but those are contradictory to true, real activism.

EB: So by the conventional definitions of art and activism there’s some dissonance between them?

FGD: You’re right to say by the conventional definitions, yes. The art system works as a professional structure, so art could be activist, but the content or activity probably wouldn’t circulate within the art world, it wouldn’t get press, it would just be something that happened. For example, if you work with a community garden to produce a theater piece to protest against development—that’s a cultural form of activism, a cultural expression of political action—which is fine, but will it have any relevance in the art world? Not necessarily. It would be something that only exists and resonates in the community itself.

EB: But does that make it an unsuccessful piece of art? That it only resonated on the community level and not on the level of the art world?

FGD: No, I think that it could be a successful art piece in any case, but we wouldn’t use the parameters of the established art system to validate it, we would validate in its context. It exists between two spheres: the sphere of community action and the sphere of established art.

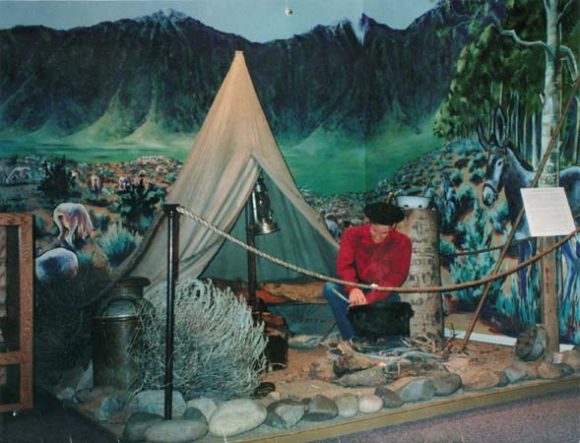

From Fernando Garcia-Dory’s “A Shepherd’s School”

EB: Can you think of a project that you’ve done that you thought was successful, in any or either sphere?

FGD: Well, I’m still running A Shepherd’s School, I started ten years ago, but I wouldn’t consider it activist. It’s more of a sustained, useful social process. It works well, and we’re developing the village that will host the headquarters for it.

EB: Can you talk a little bit more about that?

FGD: So the school started in 2004 due to the needs of shepherds that are being left alone in the mountains. They need young people who want to learn the trade, so we put together both shepherds and young people in a collaborative system for the exchange of knowledge and the reinvention of the profession of shepherding in the 21st century. The project also offered dairy workshops, and huts in the mountains that are free to live in for people who have finished their training and would like to stay. So far two people have stayed.

The course has a theory component and a practical component, in which students spend four months with a shepherd. I think it’s changed the perception of the shepherds from people who just live in the mountains to people with knowledge that is demanded. People come from the city, people with college degrees that want to learn these forms of life.

EB: So the specific markers of success for the school are —

FGD: How it’s changed the perception of the shepherd and brought new people into the profession, and how it’s created infrastructure that is free to use.

EB: So do you think the projects that you do have an audience?

FGD: Yeah, I think there’s an audience. There’s the primary audience of the people who take part in the project and the secondary audience of the people who see the project presented.

EB: And how do you think about those two separate audiences? What do you want them to do upon being a part of or witnessing your work?

FGD: Well, the primary audience isn’t really audience, they’re participants, they’re the users of the project and not a passive audience.

EB: So what about when you present the work, then—how do you think about and communicate with that secondary audience?

FGD: The secondary audience exists when I show my projects, so I go to the space where I’m going to do the show and then organize the work how it’s going to be shown. And then, if there’s a chance, I try to enlarge and expand the experience with the format of activations. We use the shows to try be spaces of activation of the work, with discussions and forms of the work so the audience can try to understand what has been experienced with the primary audience of participants.

EB: So now going to the other side, is there a piece of work you’ve done that you believe didn’t work, for whatever reason?

FGD: I think things don’t work when you are very conditioned by the art system and when there is no infrastructure for connection with the community or no continuation. It’s important to be aware of the deepness of the engagement, if it’s not deep enough then the project won’t be a real or lasting engagement or interaction. For example, a project that could’ve been better connected with the farmer’s union so it could’ve been continued, but it had only the scope and exhibition of two months, so it was limited.

EB: So how exactly would you define “working”, then, in the context of creative activism in general?

FGD: It’s something that happens when there are good feelings between the participants, when they feel they were useful in either deepening the meaning of the project or disseminating it. But it’s an evaluation you make at the end and depends on each case.

EB: It sounds like you’re saying success can mean when there’s a wide-spread understanding of what you’re trying to do?

FGD: Yes, it’s a very subjective feeling. Also, it can’t just be pure activism, it has to have some sort of art quality to it, a notion of creativity, of beauty.

EB: Right. So what change do you see your activism and practice bringing?

FGD: Well it depends on the kind of practice. In the art context, my practice is more about just diverting attention to certain questions and topics I find interesting, like food systems or rural environment. But with my projects, like what I’m doing with this village, it’s more about creating a space for other forms of life—a collective life with a land-based economy, a community of practice that’s beyond the discursive aspect of activism. With this we’re challenging ourselves with making and seeing one makes.

From “Land/Use. Blueprint for a New Pastoralism” by Fernando Garcia-Dory

EB: And can you talk a little more about your current project?

FGD: The project is rebuilding a whole abundant village as an infrastructure for farms, craft, and art production with a community of practice, a collective of people that run it and live in it.

EB: So the village will be its own sustainable economy?

FGD: That’s the goal. The goal is that the different buildings and use of the land creates a production of industry in a community of consumers. And it’s not just community supported agriculture, but community supported arts. There’s a training space, and a space for exchange between people that come and go and the more settled collective. So the people that belong to the collective can have their needs covered by the structure itself.

EB: And what is the larger goal in creating the village?

FGD: I think it’s about creating a situation where we do art with political discourse inside an economical-political structure that is in itself transformative. So it’s not so much what we talk about or how we talk about it, but where we talk about it. The context of the production is important.

EB: So creating transformative structures like this village—is this how you think social change happens?

FGD: I think social change happens through creating visible, alternative forms of life that have enough critical mass and interest. So if artists are developing these other forms of life and economies, they must be inspiring enough for others to want to work with those cultural values. Our current cultural values of competition, accumulation, capitalism—these are just part of a cultural setting created through mass media and culture, so if we can somehow develop and embody other values and other forms of life, and make them visible, then people might be able to unplug from the current system and start to work for the creation of other, better systems.

You must be logged in to post a comment.